Deep inside every atom, an invisible rule quietly keeps the universe from unraveling. It decides how electrons arrange themselves, why matter has shape and solidity, and why stars made of crushed matter can resist collapse. This rule is the Pauli exclusion principle, a century-old idea that has become one of the pillars of modern physics. Now, after years of patient listening in a silent underground laboratory, physicists have tested that rule more stringently than ever before—and found that it still holds firm.

An international collaboration using the VIP-2 experiment has carried out one of the most demanding checks ever devised for this foundational principle. Their conclusion, reported in Scientific Reports in November 2025, is both reassuring and provocative: no sign of violation appeared, even at sensitivities so extreme they stretch the imagination. If the Pauli exclusion principle can break, it does so at levels smaller than two parts in 10⁴³.

That number is so tiny it almost defies comprehension. But in the world of quantum physics, such limits are powerful. They carve away entire families of speculative theories and sharpen our understanding of what the universe allows—and what it absolutely forbids.

A Century-Old Idea Under Relentless Scrutiny

When Austrian-Swiss physicist Wolfgang Pauli proposed the exclusion principle in 1925, it was an audacious claim. He suggested that no two identical fermions, a category of particles that includes electrons, can occupy the same quantum state at the same time. This single statement explained why electrons stack neatly into atomic shells instead of collapsing inward, why solids resist compression, and why exotic stellar objects like white dwarf stars can support themselves against immense gravity.

The principle became so successful that it was woven directly into the Standard Model of particle physics. Yet physicists have never been entirely comfortable taking such a powerful rule on faith. From the beginning, they have wondered whether it is truly absolute or merely an extraordinarily good approximation.

“If the Pauli exclusion principle were violated, even at an extremely small level, the consequences would cascade from atomic physics all the way to astrophysics,” explains Catalina Curceanu, a physicist at the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics and spokesperson for the VIP-2 collaboration. The stakes could hardly be higher. A crack in this principle would signal new physics hiding beneath the familiar equations.

Listening for the Forbidden

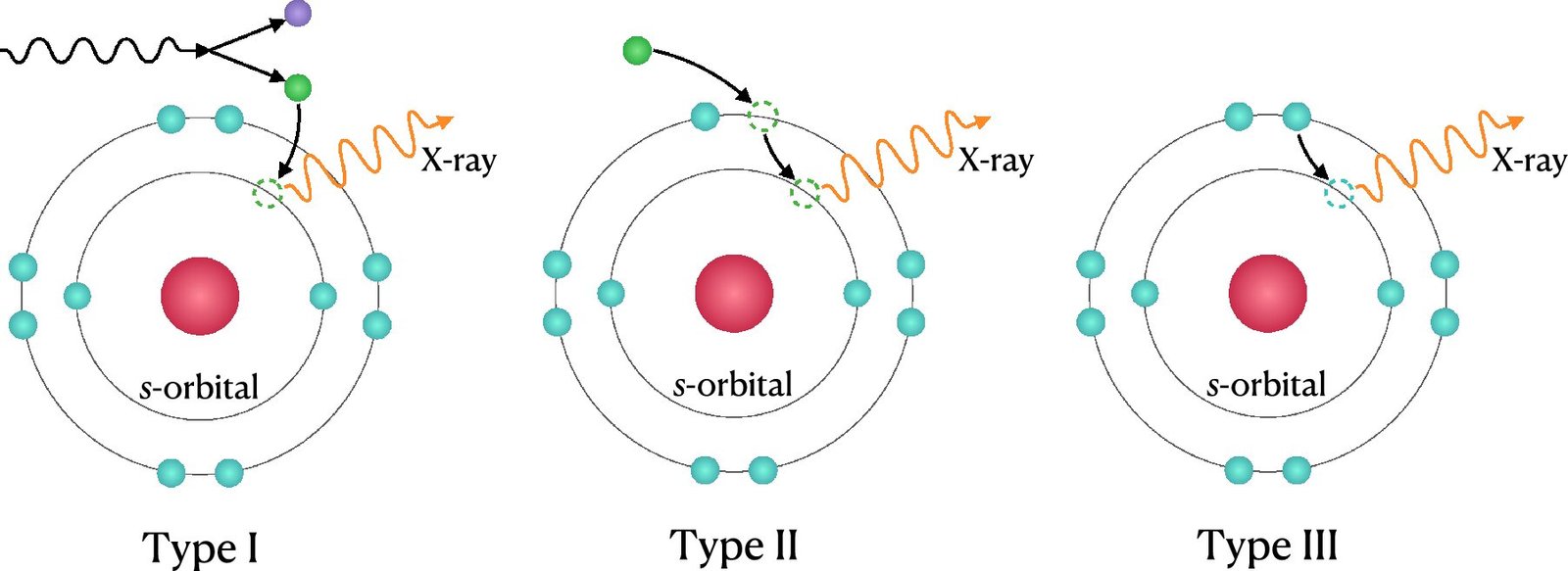

Testing a rule that is almost never broken requires a clever strategy. The VIP-2 experiment focuses on electrons inside copper atoms, watching for events that should never happen if Pauli’s principle is exact. Specifically, a violation would allow electrons to make normally forbidden atomic transitions, slipping into quantum states that are already occupied. Such transgressions would announce themselves through X-rays at precisely defined energies that standard atomic theory does not allow.

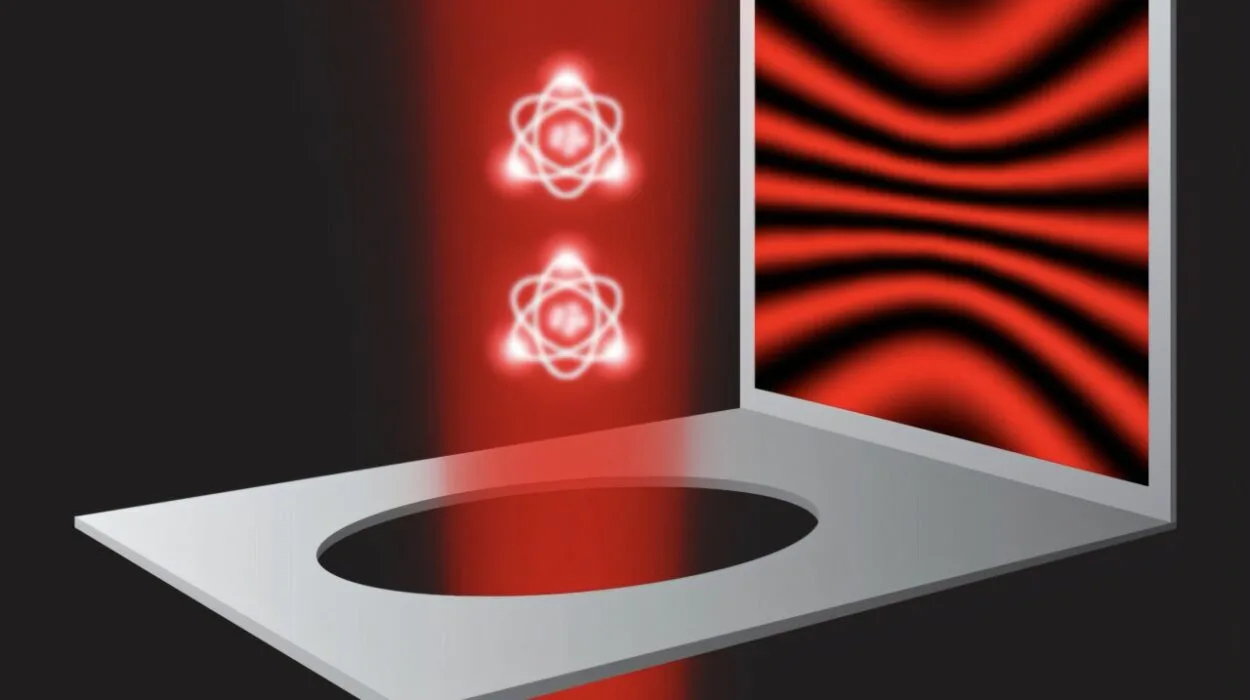

The experiment takes place at the Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy, deep underground where thick layers of rock shield sensitive instruments from cosmic radiation. In this quiet environment, the researchers used low-noise X-ray detectors capable of registering even the faintest whispers from atomic processes.

But simply watching atoms is not enough. Quantum mechanics itself imposes a subtle constraint: in a closed system, violations of the exclusion principle are forbidden from appearing at all. To overcome this, the team needed to open the system.

New Electrons, Clean Test

The solution was to inject a flood of “new” electrons into the copper targets—electrons that had never interacted with those atoms before. This setup, known as an open-system configuration, is crucial to the experiment’s power.

“Introducing electrons that have not previously interacted with the atomic system is crucial,” says Alessio Porcelli, lead author of the study. By doing this, the researchers bypassed the theoretical barrier that would otherwise hide any violation. If the Pauli exclusion principle can fail, this method gives it the opportunity to do so.

For several years, the detectors watched patiently as electrons entered the copper and settled into place. The team searched relentlessly for the tell-tale X-ray lines that would betray a forbidden transition. The detectors were ready. The analysis was precise. The silence was complete.

No anomalous X-rays appeared.

Silence That Speaks Volumes

The absence of a signal is not a disappointment in experiments like this—it is the result. From that silence, the team extracted the strongest constraint ever placed on Pauli exclusion principle violations involving electrons in atomic systems. The probability of such a violation must be smaller than two parts in 10⁴³, an astonishing level of precision.

“This is the strongest experimental constraint ever achieved for electrons in open systems,” Porcelli says. With this result, the VIP-2 collaboration has pushed the principle to a boundary so tight that many speculative ideas now find themselves cornered.

Narrowing the Possibilities Beyond the Standard Model

While the Standard Model treats the Pauli exclusion principle as exact, many proposed extensions do not. Some theories suggest subtle deviations that might emerge under extreme scrutiny. The VIP-2 result dramatically shrinks the space in which such theories can survive.

One prominent target is the Quon model. In standard quantum mechanics, particles are strictly divided into fermions and bosons, with no middle ground. Quon models blur this distinction, allowing particles to behave almost like fermions while occasionally bending the exclusion principle.

“Our result places very stringent constraints on possible deviations from standard fermionic behavior for electrons,” says Kristian Piscicchia, a leading member of the collaboration. The findings leave little room for electrons to be anything other than perfect fermions.

No Signs of Hidden Layers

The experiment also challenges ideas suggesting that electrons might possess a hidden internal structure. If electrons were not truly fundamental, but composed of smaller components, the Pauli exclusion principle might weaken slightly. The VIP-2 data show no such weakening.

Even attempts to merge quantum mechanics with gravity feel the pressure. Some quantum gravity theories predict small violations of the exclusion principle. The new limits rule out violations at levels those theories might allow, forcing theorists to rethink or refine their ideas.

“Any viable extension of quantum theory must reproduce the Pauli exclusion principle with extraordinary precision,” Curceanu says. The message is clear: whatever deeper laws govern reality, they must respect this rule almost perfectly.

Why This Result Matters

At first glance, confirming that a rule still holds may seem less exciting than discovering that it breaks. But in fundamental physics, precision is revelation. By showing that the Pauli exclusion principle survives one of the most sensitive tests ever devised, the VIP-2 experiment reinforces the foundations on which our understanding of matter rests.

This result doesn’t close the door on new physics—it sharpens the map. It tells researchers where not to look and guides them toward ideas that can survive extreme scrutiny. It also demonstrates that foundational principles are not beyond question; they earn their status through relentless testing.

The work was supported by the Foundational Questions Institute (FQxI), whose commitment to probing the deepest assumptions of physics made this demanding experiment possible. And the story is not over. The upcoming VIP-3 experiment aims to push sensitivity even further, continuing the quiet, patient search for cracks in one of nature’s most steadfast rules.

If the universe hides deeper truths beneath quantum mechanics, they must be compatible with the Pauli exclusion principle to an almost unimaginable degree. For now, at least, this century-old rule remains unbroken—holding atoms together, stars upright, and our theories firmly in place.

Study Details

Alessio Porcelli et al, Strongest constraint on the parastatistical Quon model with the VIP-2 measurements, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-25444-z