Somewhere in the galaxy, a star that already died is still making noise. Not the gentle kind, but sharp, blinding flashes of radio energy that last less than the blink of an eye and yet can be detected across cosmic distances. These signals, known as fast radio bursts, have puzzled astronomers for years. They arrive suddenly, vanish almost instantly, and leave behind a trail of questions. Now, a new study has taken a major step toward explaining how some of these cosmic screams may be born, by simulating the most violent shocks ever modeled in the universe.

The research, published in Physical Review Letters, focuses on magnetars, a rare and extreme kind of neutron star, and on something evocatively named monster shocks. For the first time, scientists have simulated these shocks across an entire magnetar environment, watching how invisible waves transform into explosive radio flashes. What emerges is a story of unstable stars, runaway waves, and plasma pushed beyond its limits.

A Star Wrapped in Impossible Magnetism

Magnetars are young by cosmic standards, typically only a few thousand years old. They are the collapsed cores of massive stars, squeezed into incredibly small volumes and wrapped in magnetic fields so intense they defy everyday intuition. At their surfaces, these fields can reach 10¹⁵ gauss, making magnetars some of the most magnetized objects known.

This extreme magnetism drives relentless activity. Magnetars produce frequent X-ray bursts, sudden releases of energy that signal internal stress and motion. Over time, astronomers began to suspect that these same objects might also be behind fast radio bursts. That suspicion gained powerful support in 2020, when a magnetar in our own galaxy, SGR 1935+2154, released a burst detected both in X-rays and radio waves at the same moment.

The link was tantalizing, but incomplete. The missing piece was a physical mechanism capable of turning magnetar violence into the razor-sharp radio signals astronomers observe. This is where monster shocks enter the story.

The Journey of a Wave That Refuses to Stay Small

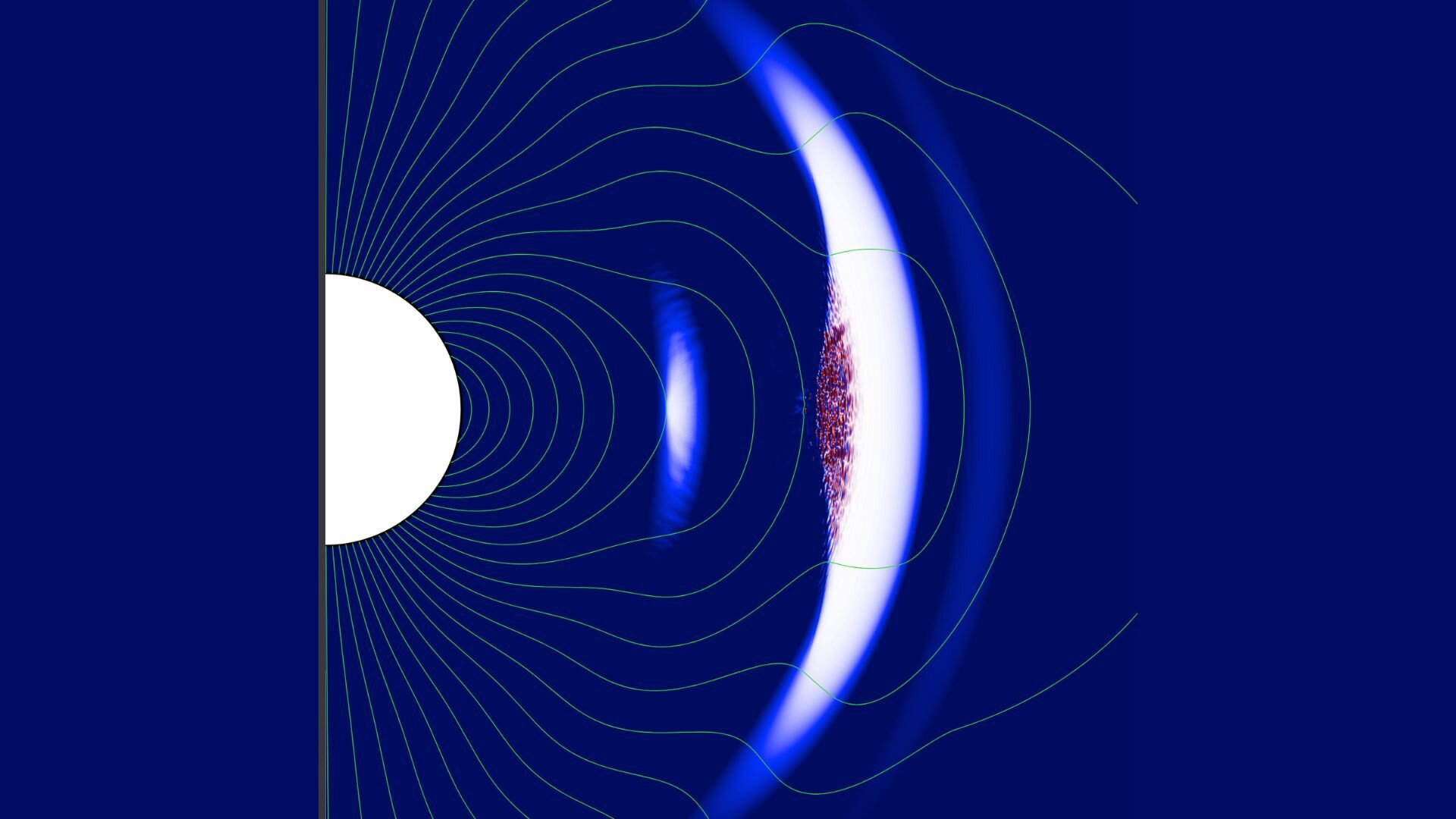

Inside a magnetar, nothing is truly at rest. The star’s interior is still settling from its violent birth, and its crust can crack and shift. These disturbances launch powerful fast magnetosonic waves into the surrounding plasma, a thin, magnetized environment called the magnetosphere.

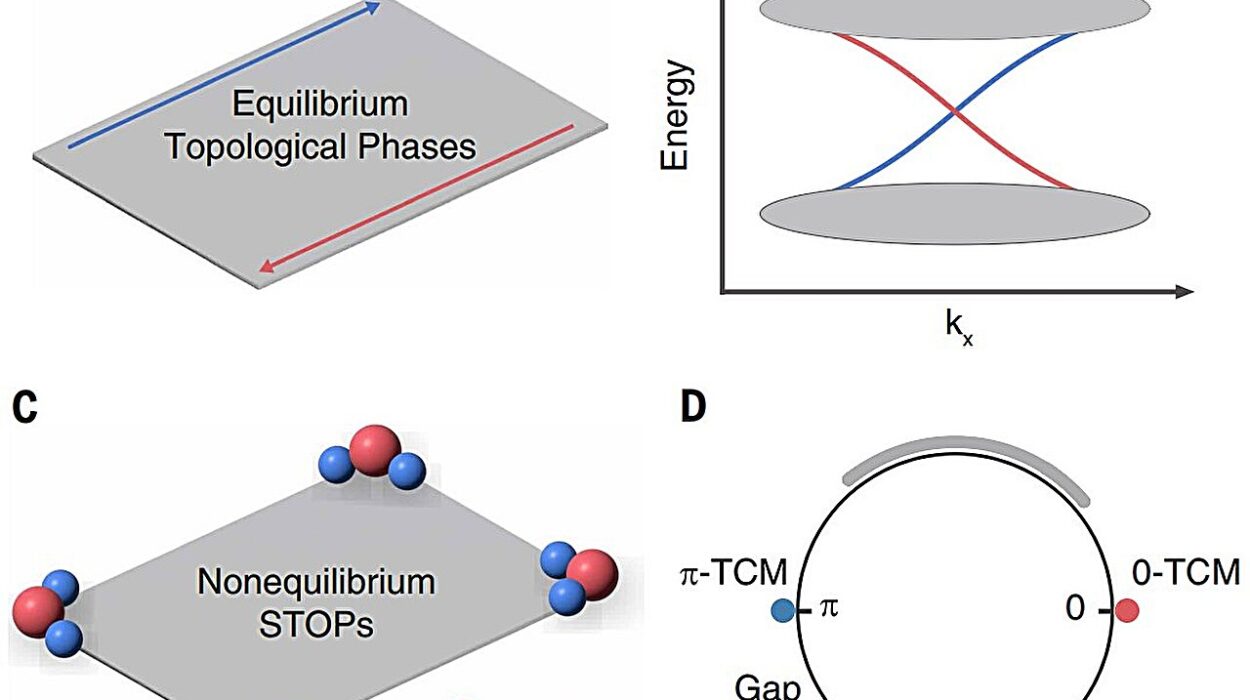

At first, these waves behave as expected. They spread outward, their amplitude slowly decreasing with distance. But the magnetosphere itself is changing even faster. As the waves move away from the star, the background magnetic field drops off sharply. The result is a strange reversal: even as the wave weakens, it becomes stronger relative to its surroundings.

Eventually, the wave’s strength rivals the magnetic field itself. At that point, smooth motion breaks down. The wave steepens abruptly and collapses into a monster shock, an event so extreme it earns its name.

According to the study’s lead author, Dominic Bernardi of Washington University in St. Louis, these shocks are unlike anything else seen in astrophysics. They are not just barriers that plasma crashes into. Instead, they actively pull plasma toward themselves, setting the stage for something far more energetic.

A Shock That Vacuums Space Clean

Most shocks in space work like traffic jams. Material piles up, slows down, and heats as it crosses the shock front. Monster shocks operate differently. The plasma ahead of them is effectively sucked into the shock, accelerating as it goes. Bernardi likens the process to a vacuum cleaner drawing in dust, except here the dust is charged particles and the acceleration pushes them to extraordinary energies.

This acceleration happens before the plasma even reaches the shock front. When the energized particles finally slam into the shock, their stored energy is released in a burst. Combined with the magnetar’s immense magnetic field, this process dissipates magnetic energy with an efficiency far beyond that of ordinary astrophysical shocks.

Crucially, this violent release produces coherent radio emission, meaning the particles emit radio waves in sync, amplifying the signal. This coherence is exactly what fast radio bursts require.

Building the Universe Inside a Computer

Until now, monster shocks had only been studied in simplified settings, usually assuming straight magnetic fields and idealized geometry. Real magnetars are messier. Their magnetic fields curve and twist into a dipolar magnetosphere, more like a bar magnet than a straight line.

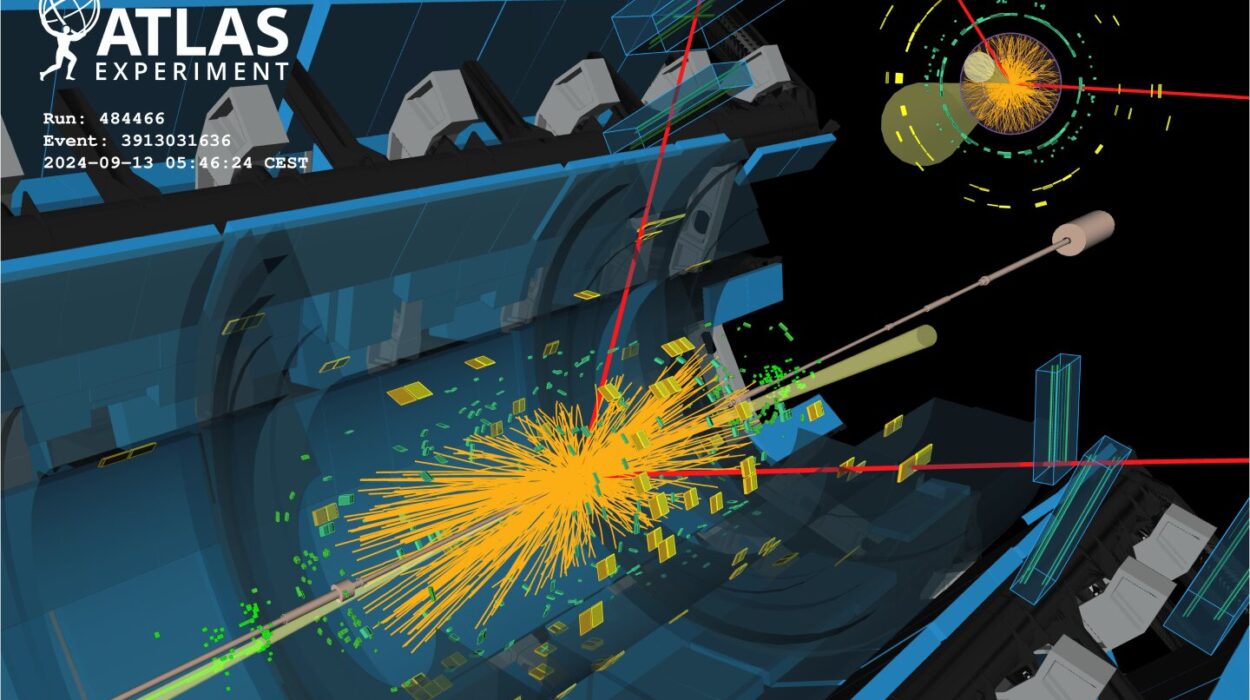

The new study breaks this limitation. Using 2D global particle-in-cell simulations, the researchers modeled monster shock formation across an entire magnetar magnetosphere for the first time. The simulations were run with the team’s Aperture code, designed to track both the large-scale structure of the magnetosphere and the tiny, fast-moving particles inside it.

This was no small feat. The challenge lay in resolving vastly different scales at once, from the star-sized magnetic environment down to the microscopic physics of plasma motion. To bridge the gap, the team used axisymmetry to reduce the problem to two dimensions, employed logarithmic grids to span distances efficiently, and relied on analytic scaling relations to connect the pieces.

What emerged from these simulations was a detailed, dynamic picture of monster shocks in action.

Where the Radio Light Is Born

The simulations confirmed that monster shocks accelerate plasma to extreme Lorentz factors, meaning the particles approach the speed of light. This acceleration scales directly with the background magnetization and the wavelength of the original wave that triggered the shock. In fact, the acceleration turned out to be slightly more efficient than earlier theoretical predictions suggested.

Just as important, the simulations revealed the shocks’ spatial structure. Coherent radio emission does not emerge everywhere. Instead, it is confined to a narrow band around the magnetar’s magnetic equator, spanning roughly 7 to 23 degrees of latitude, depending on wavelength.

Near this equatorial region, the shocks remain quasi-perpendicular to the magnetic field. Here, the accelerated plasma organizes itself into solitons, compact, coherent peaks in density and magnetic field. Charged particles inside these structures begin to gyrate together, moving in phase. This synchronized motion powers a synchrotron maser mechanism, generating radio waves in the GHz range.

At higher latitudes, the story changes. The magnetic field lines align more closely with the shock, suppressing the conditions needed for coherence. In these regions, the radio signal fades before it can form.

Numbers That Sound Like Observations

By combining their simulation results with analytic scaling relations, the researchers translated their findings into observable predictions. Under realistic magnetar conditions, the numbers line up strikingly well with what astronomers actually see.

For a magnetar with a surface magnetic field of 10¹⁵ gauss producing an X-ray burst with a luminosity of 10⁴² erg/s, the model predicts radio emission peaking near 0.22 GHz, with luminosities around 10³⁸ erg/s and durations of about 0.5 milliseconds per shock.

When applied to SGR 1935+2154, the same framework predicts emission near 1.4 GHz, matching the frequency range detected by STARE2, which observed the burst between 1.281 and 1.468 GHz. The predicted luminosities are also consistent with measurements from both STARE2 and CHIME.

Perhaps most importantly, the model resolves a long-standing efficiency problem. Traditional shock physics suggests that coherent radio emission should be vanishingly weak in highly magnetized environments. Monster shocks overturn this expectation. Because plasma is pre-accelerated before entering the shock, the efficiency of radio emission is dramatically boosted, reaching levels capable of explaining real fast radio bursts.

Flickers Within the Flash

The simulations also hint at why some fast radio bursts show internal structure. A single fast magnetosonic wave is not always alone. A train of waves can follow, each one capable of generating its own shock. This can produce multiple radio flashes separated by roughly 0.6 milliseconds, creating fine substructure within a single observed burst.

Such timescales closely resemble patterns already seen in some fast radio burst data, suggesting that monster shocks may naturally reproduce not just the overall signal, but its intricate details.

Why This Story Matters

Fast radio bursts are among the most enigmatic signals in modern astronomy. They are brief, brilliant, and distant, and they carry information about extreme physics that cannot be replicated on Earth. By simulating monster shocks in a realistic magnetar magnetosphere, this research provides the strongest evidence yet that magnetars can generate fast radio bursts through a concrete, testable mechanism.

The study shows how waves born deep inside a restless star can grow, steepen, and ultimately release their energy as coherent radio light. It explains why the emission is strong, why it appears at certain frequencies, and why it comes from specific regions around the star. It even hints at why bursts sometimes flicker internally rather than arriving as smooth flashes.

There are still open questions. The researchers note that extremely luminous cosmological bursts may be too powerful for radio waves to escape, and that larger simulations will be needed to track the long-term evolution of these shocks. But the foundation is now in place.

Monster shocks are no longer just a theoretical curiosity. They are simulated, measured, and increasingly connected to what telescopes see. In revealing how some of the universe’s strongest magnetic fields can produce its briefest radio signals, this work brings us closer to understanding how dead stars still manage to speak across the cosmos.

Study Details

Dominic Bernardi et al, Global Kinetic Simulations of Monster Shocks and Their Emission, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/y9p7-1zms.