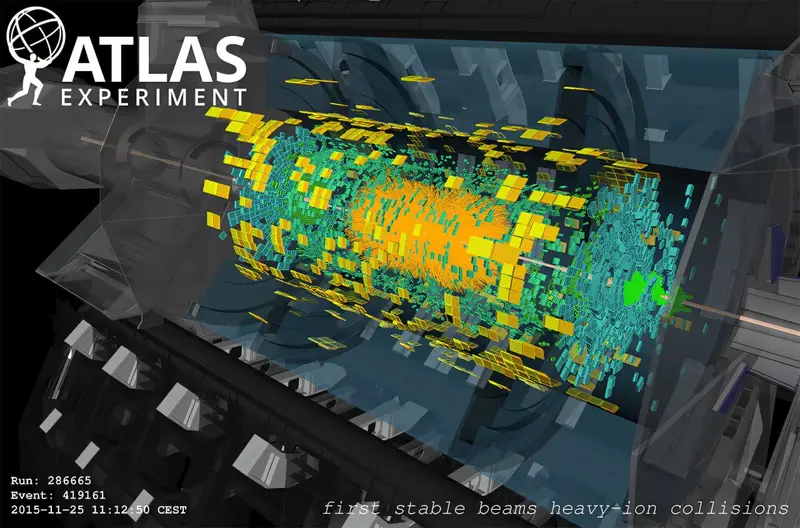

Deep beneath the French-Swiss border, inside a circular tunnel stretching 17 miles around, lead ions race toward each other at nearly the speed of light. When they collide inside the Large Hadron Collider, something extraordinary happens. For a fleeting moment, matter behaves not as individual particles, but as a single, flowing whole. Scientists have now uncovered new evidence that this motion is not random chaos, but a coordinated response driven by pressure, echoing conditions from the earliest moments after the Big Bang.

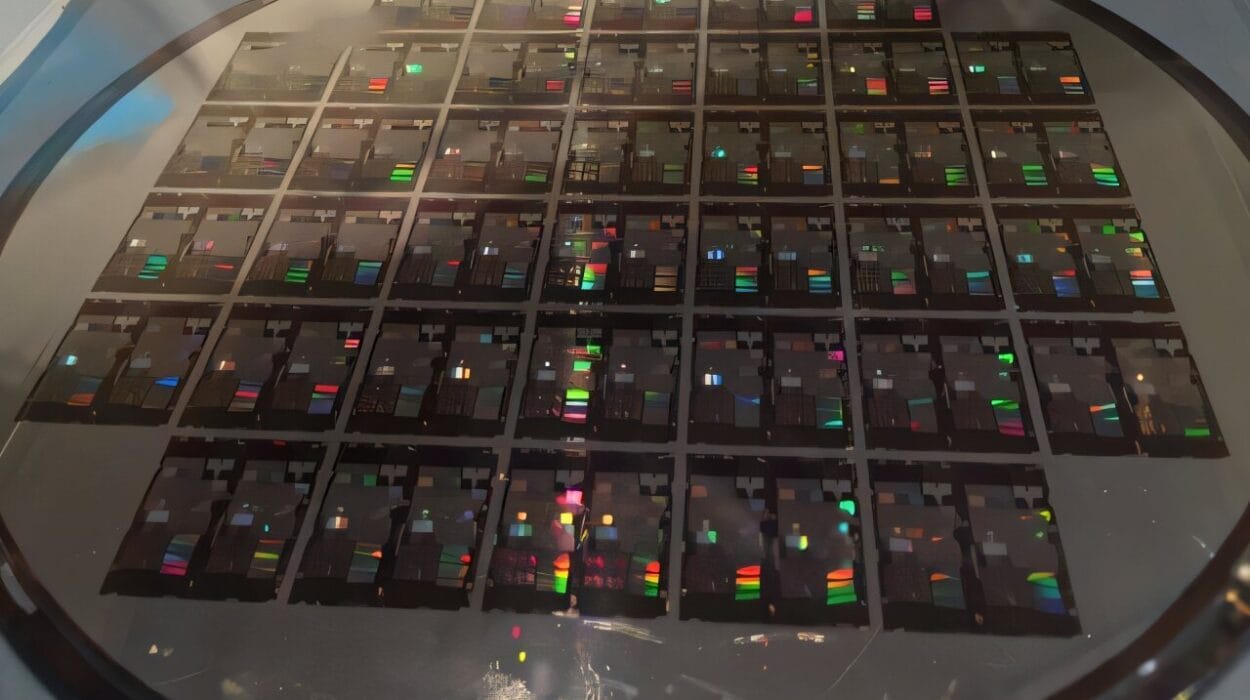

By studying heavy ion collisions recorded by the ATLAS experiment at CERN, researchers have shown that particles streaming outward from these violent encounters move collectively, pushed by powerful pressure gradients created in the collision itself. This phenomenon, known as radial flow, reveals fresh details about the strange, hot substance formed in these events: the quark-gluon plasma, or QGP.

The findings, published by the ATLAS Collaboration in Physical Review Letters, draw on years of collaboration between experimentalists and theorists, with scientists from Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook University playing leading roles. Together, they are piecing together how matter behaved when the universe was newborn.

A Fireball Hotter Than the Sun Can Imagine

When two lead ions collide inside the LHC, the energy released is so immense that temperatures soar to more than 250,000 times hotter than the sun’s core. Under these extreme conditions, protons and neutrons do not survive intact. They melt, freeing their internal components, quarks and gluons, which normally remain locked inside nuclear particles.

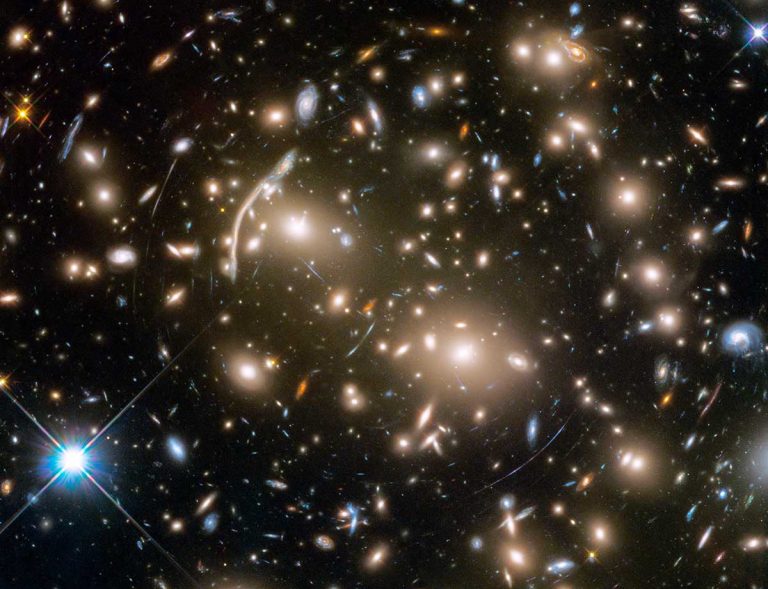

For an instant, these liberated building blocks form the quark-gluon plasma, a state of matter thought to have filled the universe microseconds after the Big Bang. Instead of behaving like a thin gas, the QGP flows like a liquid. And not just any liquid. Earlier experiments revealed it behaves almost like a perfect one, with astonishingly low resistance to motion.

Understanding how this plasma moves is crucial. Flow patterns act like fingerprints, revealing the internal forces shaping the fireball. The new ATLAS results focus on a type of motion that had been less explored, but turns out to be deeply revealing.

A Story That Began with an Ellipse

To understand why radial flow matters, scientists look back to an earlier chapter written at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, or RHIC, at Brookhaven. When RHIC first turned on in 2001, it collided gold ions and detected something unexpected. Particles did not spray out evenly in all directions. Instead, they formed an elliptic flow, with more particles emerging along certain directions than others.

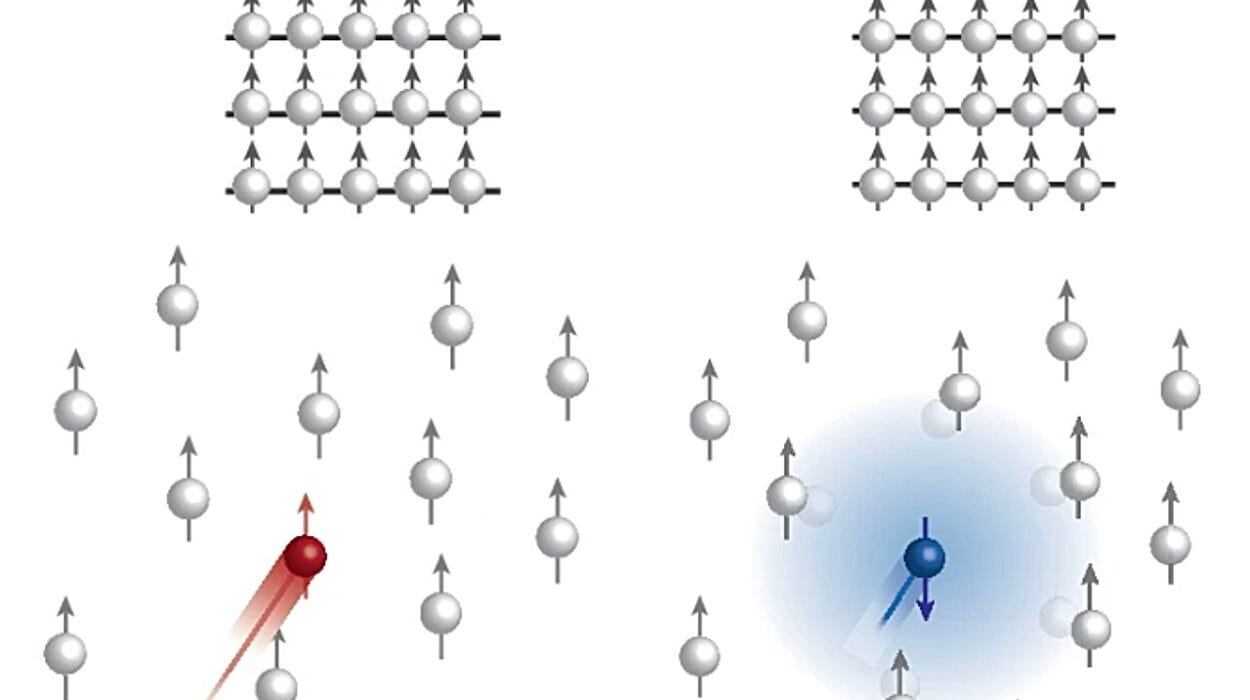

This pattern was traced to the shape of the collision zone. When two spherical gold ions collide off-center, the overlapping region resembles a flattened football. Pressure builds unevenly inside this shape, pushing more particles out along its wider sides. The strength of this flow revealed that quarks and gluons were interacting strongly, even after being freed, behaving as a nearly frictionless liquid with extremely low shear viscosity.

Elliptic flow became one of the key discoveries proving the existence of the quark-gluon plasma. But it told only part of the story.

The Quiet Power of an Outward Push

While elliptic flow depends on shape, radial flow comes from something simpler and more universal: the outward pressure of the fireball itself. Imagine the QGP as a tiny, ultra-hot droplet that wants to expand in all directions at once. This symmetric expansion pushes particles outward radially, regardless of any geometric asymmetry.

Physicist Jiangyong Jia, who led the new ATLAS analysis, explains that while radial flow had been observed before, scientists had not fully examined how fast and slow particles were correlated within each collision, or how those relationships varied with momentum and direction along the beam.

That gap began to close in 2020, when theorists Bjoern Schenke, Derek Teaney, and Chun Shen developed a framework linking momentum-dependent radial flow to the size of the QGP fireball. Their idea was elegant. For collisions producing the same total number of particles, a smaller, denser fireball should generate a stronger pressure gradient than a larger, more spread-out one.

Stronger pressure means stronger push.

Following the Speed of Particles

The theory made a clear prediction. Smaller QGP droplets should fling out more fast-moving particles and fewer slow ones, compared with larger droplets. To test this idea, physicist Somadutta Bhatta turned to the ATLAS data, examining millions of collision events.

Using two-particle correlations, a method already proven powerful in elliptic flow studies, Bhatta tracked how particle momenta fluctuated from one event to the next. He looked at particles moving transversely, sideways relative to the beam, and examined how their speeds related to the inferred size of the fireball.

The results lined up with theory. Events corresponding to smaller QGP systems showed exactly the expected pattern: an increase in high-momentum particles and a decrease in low-momentum ones. Crucially, this relationship held true at all angles along the beam direction.

Bhatta likened the effect to puncturing balloons filled with the same amount of water. The smaller balloon, under higher pressure, sends water shooting out faster. In the same way, the compact QGP fireballs release particles with greater speed.

A Collective Motion, No Matter the Angle

What emerged from the analysis was a striking confirmation that radial flow is not a localized or directional quirk. It is a global collective phenomenon. Every particle in the event participates in the outward push, carrying the imprint of the fireball’s internal pressure.

As Peter Steinberg, a co-author on the ATLAS paper, put it, when a single speck of QGP is created, the overall flow is directly tied to how particle speeds are distributed. High-momentum particles rise as low-momentum ones fall, all without requiring any special shape to drive the expansion.

The ATLAS findings are reinforced by complementary measurements from the ALICE experiment, another detector at the LHC. ALICE analyzed similar collisions using different methods and reported consistent results in the same journal issue, strengthening confidence that the observed radial flow reflects genuine properties of the quark-gluon plasma.

Listening to the Plasma’s Resistance

Beyond confirming collective behavior, radial flow opens a new window into the internal character of the QGP. In particular, it offers a way to probe bulk viscosity, a measure of how resistant a substance is to being compressed or expanded uniformly.

Bulk viscosity differs from shear viscosity, which describes resistance to layers sliding past each other and helped establish the QGP’s nearly perfect fluidity. In a radially expanding system, even a fluid with low shear viscosity can be slowed if it resists compression.

By measuring how strongly the QGP expands outward, scientists can test how compressible it is. Radial flow becomes a sensitive probe of this subtle property, adding a new dimension to the study of hot nuclear matter.

Why Shape-Free Flow Matters

One of the most promising aspects of radial flow is that it does not depend on the detailed shape of the fireball. This makes it especially valuable for studying small systems, created when nuclei much lighter than lead or gold collide.

In these tiny collisions, determining the exact shape of the QGP is extremely challenging. Radial flow sidesteps that problem entirely. If collective expansion is observed without relying on geometry, scientists gain a powerful tool to investigate whether even the smallest droplets of QGP behave like a fluid.

The work also strengthens the scientific bridge between RHIC and the LHC. By applying ideas and techniques across facilities operating at different energies, researchers can test whether the same physics holds under varied conditions. For Jia, who works with both the ATLAS and STAR collaborations, this cross-fertilization is key to progress.

Why This Research Matters

At its heart, this research is about understanding how matter behaves under the most extreme conditions imaginable. The quark-gluon plasma is not just an exotic state created in laboratories. It is a relic of the universe’s earliest moments, when everything we know today was still taking shape.

By showing that radial flow is a true collective phenomenon driven by pressure and fireball size, scientists gain a clearer picture of how the QGP expands, cools, and transforms back into ordinary matter. These insights refine our understanding of fundamental forces and the behavior of quarks and gluons when freed from confinement.

Each new flow measurement adds another piece to the story of the early universe, written not in stars or galaxies, but in the fleeting motion of particles born from fireballs smaller than an атом. Through them, scientists continue to listen to matter itself, learning how it once moved together at the dawn of time.

Study Details

G. Aad et al, Evidence for the collective nature of radial flow in Pb+Pb collisions with the ATLAS detector, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/ldcn-r2lq

S. Acharya et al, Long-range transverse-momentum correlations and radial flow in Pb-Pb collisions at the LHC, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/l36g-6f46