Quantum computers promise to tackle problems that overwhelm even the fastest classical machines, yet behind that promise sits a surprisingly ordinary challenge: memory. No matter how exotic a computer may be, it still needs a place to store information quickly, reliably, and without wasting energy. For quantum systems, this challenge is especially severe. They demand memory components that can operate at extreme conditions while introducing as few errors as possible.

This is where superconducting memories enter the story. Built from superconductors, materials that carry electrical current with zero resistance when cooled below a critical temperature, these memories offer a tantalizing advantage. They can be faster and far more energy-efficient than conventional technologies. But for years, their promise has been weighed down by practical limits. Many designs struggle with high error rates. Others are too bulky to scale into large, usable systems.

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a team of researchers set out to confront these obstacles directly. Their work, reported in Nature Electronics, introduces a new kind of superconducting memory that aims to be both compact and dependable. The result is a small but meaningful step toward memory systems that could one day support fault-tolerant quantum computers.

When size and reliability refuse to cooperate

Superconducting memory has long lived with a frustrating trade-off. Traditional logic-based superconducting memory cells tend to occupy a large footprint, which makes it difficult to pack many of them together. This limits scaling and restricts how powerful a system can become.

Nanowire-based designs appeared to offer a solution. Nanowires, which are one-dimensional nanostructures with distinctive optoelectronic behavior, allow memory cells to shrink dramatically. Yet this miniaturization has come at a cost. Previous nanowire-based superconducting memories often suffered from high error rates, making them unreliable when assembled into larger arrays.

The MIT team framed the problem clearly in their paper. Scalable superconducting memory is essential for building low-energy superconducting computers and fault-tolerant quantum computers, but existing approaches fall short in either size or reliability. Their goal was not just to make memory smaller, but to make it stable enough to function in realistic systems.

A memory built from loops and patience

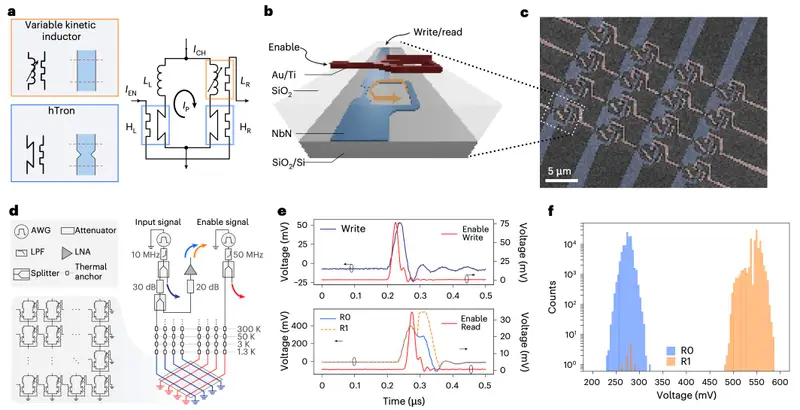

The researchers’ solution centers on a carefully engineered nanowire-based superconducting memory array. Instead of focusing on a single memory cell, they designed and demonstrated a 4 × 4 array, intentionally structured for scalable row-column operations. This architecture is a key step toward larger, more complex memory systems.

Each memory cell is built around a superconducting nanowire loop. Inside that loop sit two superconducting switches and a kinetic inductor. The switches respond to changes in temperature, while the kinetic inductor resists sudden changes in electrical current. Together, these components guide current along predictable paths, helping the cell remain stable during operation.

The array operates at 1.3 K, a temperature where superconductivity can be reliably maintained. At this extreme cold, the researchers implemented and characterized multiflux quanta state storage, a method that allows magnetic flux to represent stored information. Reading the data is destructive, meaning the act of reading clears the stored state, a known and manageable behavior in superconducting memory systems.

Writing information with a pulse of heat

At the heart of this memory is an elegant method for writing data. Information is written and read using carefully timed electrical pulses sent to specific cells in the array. When a pulse arrives, it briefly heats one of the nanowire switches. This small rise in temperature increases the switch’s resistance, just enough to allow a magnetic flux to be injected into the loop.

That magnetic flux is the memory. Depending on its state, it encodes a 0 or a 1. Once the electrical pulse ends, the nanowire cools back down and returns to its superconducting state. The flux becomes trapped inside the loop, quietly preserving the stored information.

The kinetic inductor plays a crucial role during this process. By resisting abrupt changes in current, it ensures that the system evolves smoothly, preventing unintended disturbances that could corrupt the stored data. The result is a memory cell that behaves predictably, even as it transitions between writing, storing, and reading.

Chasing errors until they almost disappear

Reliability is where this new design truly distinguishes itself. Through careful optimization of the write- and read-pulse sequences, the researchers minimized bit errors and expanded the operating margins of the memory. The performance observed in initial tests was striking.

The array demonstrated a minimum bit error rate of 10⁻⁵, which translates to roughly one error in 100,000 operations. Compared with many superconducting memories introduced in recent years, this represents a substantial improvement. Lower error rates are not just a technical detail; they are a prerequisite for scaling memory systems into larger, functional arrays.

To better understand how and why their design worked so well, the team also relied on circuit-level simulations. These simulations revealed the memory cell’s internal dynamics, explored its performance limits, and tested its stability under varying pulse amplitudes. This deeper insight strengthens confidence that the observed reliability is not accidental, but rooted in the structure of the design itself.

Density as a quiet measure of progress

Beyond error rates, the researchers also reported a notable achievement in functional density. Their memory array reached 2.6 Mbit cm⁻², reflecting how efficiently information can be packed into a given area. Density matters because every additional bit stored without increasing size brings scalable superconducting systems closer to practicality.

The row-column architecture of the array further reinforces this progress. By demonstrating that nanowire-based memory can be addressed in an organized, scalable way, the work moves beyond isolated proof-of-concept devices toward architectures that resemble real computing systems.

Why this step forward matters

This research does not claim to solve every challenge facing superconducting memory, but it addresses several of the most persistent ones at once. By combining compact nanowire-based cells, a scalable array design, and a significantly reduced error rate, the MIT team has shown that reliability and miniaturization do not have to be enemies.

For quantum computers and low-energy superconducting computers, memory is not a supporting actor. It is a core requirement that shapes performance, efficiency, and feasibility. A memory system that wastes little energy, occupies minimal space, and rarely makes mistakes brings these machines closer to operating outside the lab.

Perhaps most importantly, this work suggests a direction forward. The researchers note that their design can be further improved and scaled, opening the door to even more reliable and higher-performing systems. In the quiet loops of superconducting nanowires, cooled to near absolute zero, a practical future for quantum memory is beginning to take shape.

Study Details

Owen Medeiros et al, A scalable superconducting nanowire memory array with row–column addressing, Nature Electronics (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41928-025-01512-0