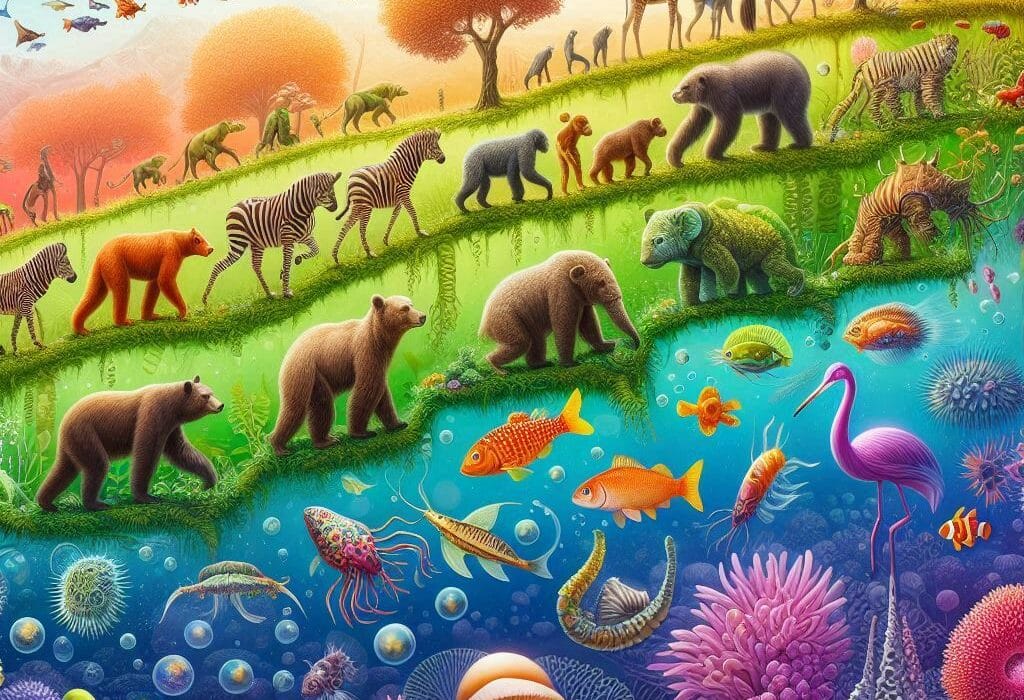

Sleep feels intimate and personal, something that happens quietly behind closed eyes. Yet beneath that stillness, brains hum with activity. For centuries, scientists have tried to understand what truly happens during sleep and why it is so essential that nearly every animal on Earth seems unable to live without it. From mammals and birds to fish, amphibians, and even insects, sleep appears again and again, reshaped by evolution but never erased.

For neuroscientists, the most revealing clues come from listening to the brain itself. Nerve cells communicate through electrical signals, and when billions of them fire together, they create patterns known as brain rhythms. These rhythms rise and fall during sleep, offering a kind of electrical storytelling about what the brain is doing when consciousness fades.

One rhythm, in particular, has long stood out. Known as the infraslow rhythm, it unfolds at a glacial pace, far slower than most other brain waves. For years, it was mainly observed in mammals and linked to non-rapid eye movement sleep, or NREM sleep, a phase associated with deep rest. But a new study has now shown that this rhythm’s roots reach much further back in time than anyone expected.

A Question That Began With Reptiles

The story begins in 2011, when neuroscientist Paul-Antoine Libourel joined a sleep research team at the Lyon Neuroscience Center. At the time, his focus was on understanding REM sleep, the stage of sleep famously tied to vivid dreaming in humans. But Libourel carried a deeper curiosity with him. He wanted to know where sleep states came from in the first place.

To answer that, he turned not to humans or laboratory mice, but to reptiles. These animals are ectothermic, meaning their body temperature depends on the environment. Mammals and birds, by contrast, are homeothermic, generating their own heat and already known to show REM sleep. Reptiles share a common ancestor with both groups, making them a living window into the past.

Libourel and his colleagues wanted to know whether sleep states like those seen in mammals emerged only after warm-blooded animals appeared, or whether their foundations were already present in species that lived roughly 300 million years ago.

Listening to Sleeping Brains in the Wild

Studying sleep across species is not easy. Brain activity must be recorded with precision, often in animals that are small, delicate, or easily stressed. To make this possible, the researchers implanted tiny electrodes on or inside the brains of their animal subjects. These electrodes captured the faint electrical signals produced as neurons communicated during sleep.

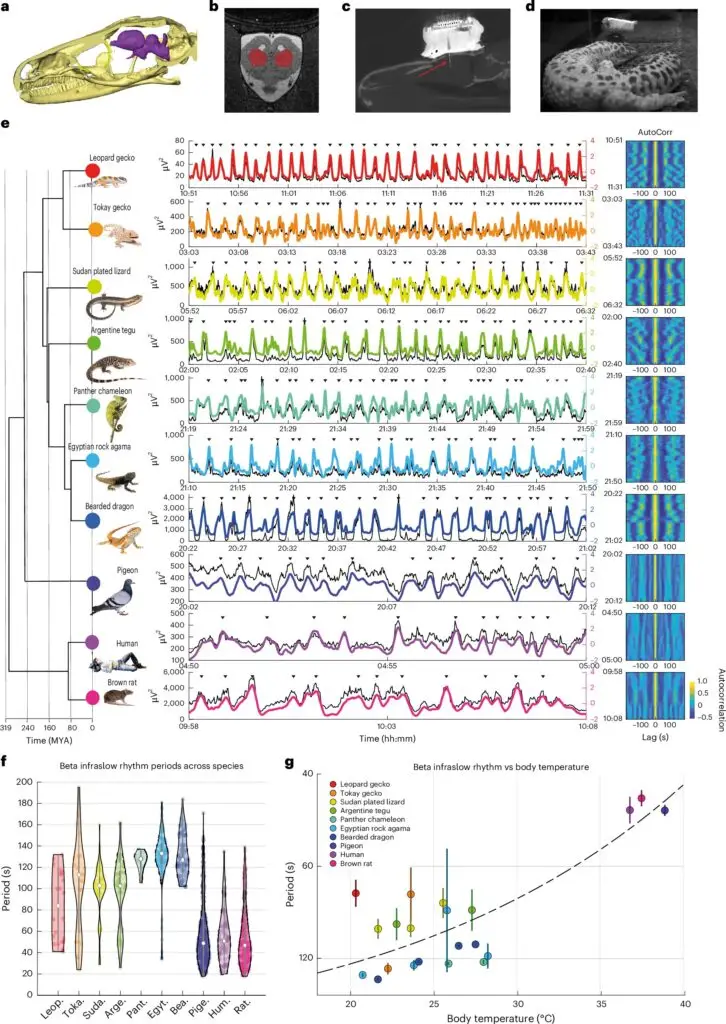

Because some lizards are small, the team worked with the Lyon Institute of Nanotechnology to design a miniature, low-power biologger capable of recording brain activity without disrupting the animal’s natural behavior. This device, later commercialized by Manitty, could simultaneously track brain rhythms, physiology, and behavior. It was powerful enough to be used not only in animals, but also in humans sleeping at home.

The researchers didn’t stop at brain activity alone. They also recorded eye movements, heart rate, breathing rate, and muscle tone, building a rich, synchronized picture of what sleep looked like across the whole body. With the support of Dr. Antoine Bergel, they even measured vascular activity using functional ultrasound imaging, applying this technique to both mice and bearded dragons.

This approach allowed the scientists to see sleep not as a single isolated process in the brain, but as a coordinated, body-wide event.

Seven Lizards and a Hidden Signal

The new study, published in Nature Neuroscience, focused on seven different lizard species: the leopard gecko, tokay gecko, Sudan plated lizard, Argentine tegu, panther chameleon, Egyptian rock agama, and bearded dragon. These animals vary widely in size, behavior, and ecology, making them ideal candidates for exploring whether a common sleep rhythm truly existed among reptiles.

As the data accumulated, a striking pattern emerged. Across species, the researchers observed the same infraslow rhythm previously described in mammals. It was not faint or fleeting. It appeared consistently, rising and falling in a slow, steady cadence during sleep.

Even more surprising was how familiar it looked. The rhythm closely resembled the infraslow activity seen during NREM sleep in mammals. Its presence in reptiles suggested that this was not a recent evolutionary innovation, but something far older.

A Rhythm That Belongs to the Whole Body

What made the discovery even more compelling was that the infraslow rhythm was not confined to the brain. It was accompanied by changes in physiological processes and peripheral vascularization, meaning blood flow throughout the body shifted in sync with the brain’s slow pulses.

This revealed the rhythm as a global, organism-wide phenomenon, not just a local brain event. Sleep, in this sense, appeared as a deeply integrated state, coordinating brain activity, circulation, and bodily functions together.

In mammals, similar rhythms have been proposed to help with brain “cleaning” processes, potentially aiding the removal of metabolic waste through cerebrospinal fluid flow. The rhythm is also associated with gentle fluctuations in vigilance, possibly allowing sleeping animals to periodically monitor their environment and reduce the risk of predation.

While these ideas have not yet been tested in lizards, the resemblance is striking enough to raise fascinating questions about shared functions across vastly different animals.

Rethinking What Sleep States Really Are

The presence of the infraslow rhythm in reptiles, birds, rodents, and humans suggests an ancestral mechanism that predates the split between cold-blooded and warm-blooded animals. This challenges the idea that sleep states evolved independently in different lineages.

At the same time, the findings complicate how scientists think about REM and NREM sleep. If the infraslow rhythm reflects an NREM-related process in mammals, then reptiles may not experience REM and NREM sleep in the same way mammals do. Their sleep-state organization may be fundamentally different, even while sharing conserved biological processes.

This does not mean reptiles do not dream. In humans, REM sleep is strongly associated with dreaming, but the absence of a mammal-like REM structure does not rule out dream-like experiences in other animals. It simply suggests that evolution has found multiple ways to organize sleep around shared core rhythms.

Following the Rhythm Into the Past and Future

For Libourel and his colleagues, this discovery is not an endpoint but a beginning. They plan to explore other animal groups, including amphibians and fish, to see how widespread the infraslow rhythm truly is. They also aim to uncover the mechanisms that generate this rhythm and determine whether it serves the same functions across species.

Each new experiment adds another piece to a puzzle that stretches back hundreds of millions of years, to a time when the earliest ancestors of today’s animals first settled into cycles of activity and rest.

Why This Discovery Matters

Understanding sleep is about more than curiosity. Sleep is essential for survival, memory, and health, yet it remains one of biology’s deepest mysteries. By revealing that a key brain rhythm is shared across reptiles, birds, and mammals, this research shows that sleep is built on ancient foundations that have endured dramatic evolutionary change.

The discovery of the infraslow rhythm in lizards suggests that some of the most fundamental processes of sleep were already in place long before humans, or even mammals, existed. It reframes sleep not as a collection of species-specific tricks, but as a deeply conserved biological strategy.

By tracing sleep back to its evolutionary roots, scientists gain a clearer picture of why it matters so profoundly today. In every slow pulse of that ancient rhythm lies a reminder that when we sleep, we are participating in a biological tradition older than imagination, one that has been quietly sustaining life on Earth for hundreds of millions of years.

Study Details

Antoine Bergel et al, Sleep-dependent infraslow rhythms are evolutionarily conserved across reptiles and mammals, Nature Neuroscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02159-y.