For more than a century, organic chemistry has lived by a thick, trusted rulebook. These rules explain how atoms link together, how bonds form and break, and why molecules adopt certain shapes instead of others. Students memorize them. Researchers rely on them. Entire industries are built on the assumption that these principles are firm and unshakable.

But in a laboratory at UCLA, that certainty has been quietly unraveling.

Organic chemists led by Neil Garg have been asking a question that sounds almost rebellious in a field built on structure: what if some of these rules are not rules at all, but habits of thought? What if chemistry has been capable of far stranger shapes than textbooks ever dared to imagine?

That curiosity has already produced a shockwave. In 2024, Garg’s lab violated Bredt’s rule, a foundational idea that stood unchallenged for a hundred years. Now, the team has gone further, venturing into molecular territory once considered too awkward, too unstable, or simply too strange to exist. Their latest work reveals fleeting, cage-shaped molecules with double bonds that refuse to lie flat, stretching chemistry’s imagination into three dimensions it rarely visits.

A Double Bond That Refuses to Behave

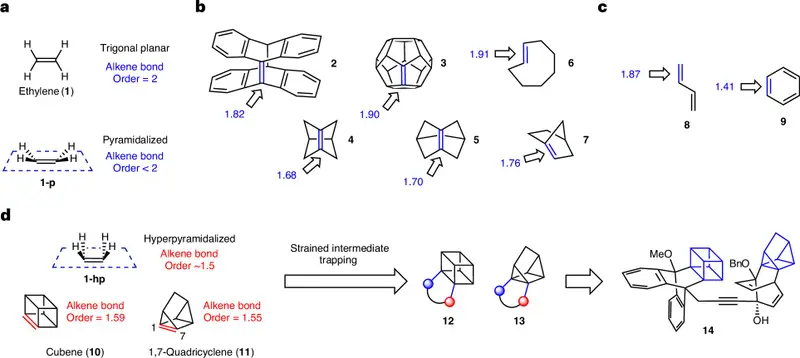

At the heart of this discovery is a familiar concept pushed to an unfamiliar extreme. Organic molecules are stitched together by three basic types of bonds: single, double, and triple. Among them, carbon–carbon double bonds, known as alkenes, are some of the most studied structures in chemistry.

Traditionally, alkenes come with a defining feature. The two carbon atoms involved adopt a trigonal planar geometry, arranging themselves and their neighboring atoms in a neat, flat plane. This flatness is so fundamental that it is often taught as an absolute truth, not a tendency.

But when Garg’s team began working with molecules called cubene and quadricyclene, that flat picture started to crumble.

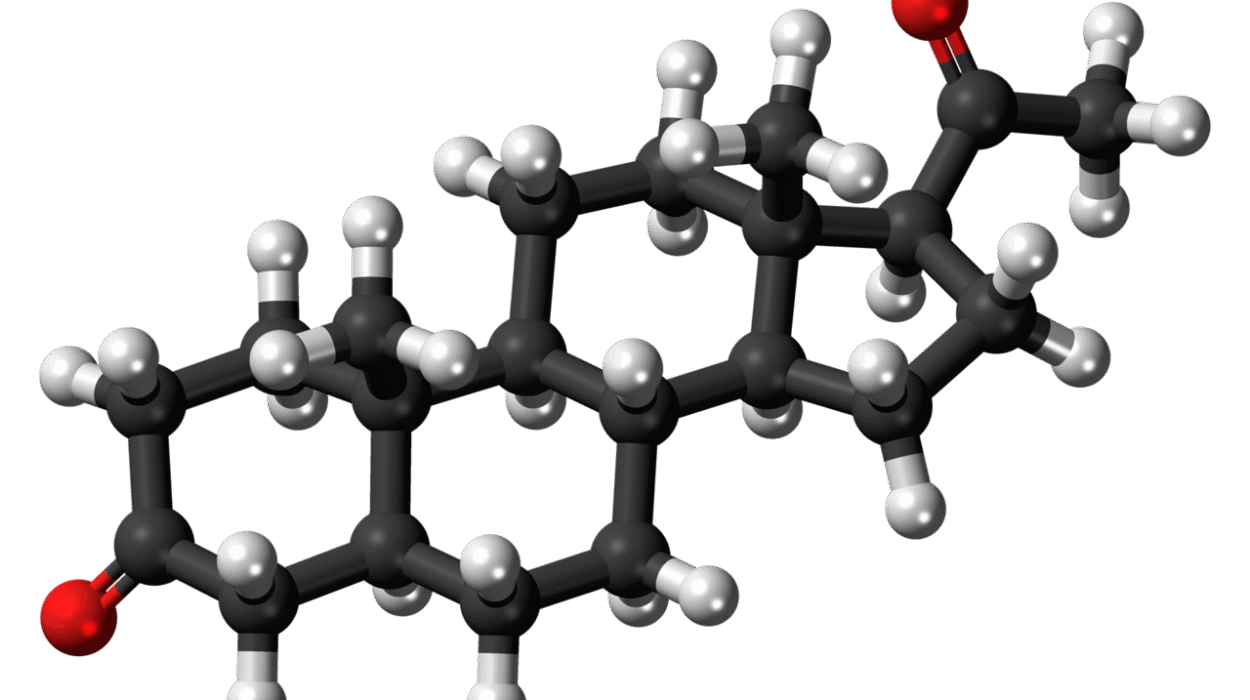

These molecules are shaped like rigid cages, forcing their atoms into uncomfortable positions. In such confined spaces, the usual rules of geometry begin to fail. The carbon atoms around the double bond cannot flatten themselves into a plane. Instead, they bend, twist, and rise out of alignment, forming shapes that look almost swollen or peaked rather than flat.

The researchers describe these carbon atoms as hyperpyramidalized, a term that captures just how dramatically the structure departs from expectation. The double bond still exists, but it is strained, distorted, and weaker than what chemists are used to seeing.

Bond Orders That Live Between the Numbers

One of the most striking aspects of cubene and quadricyclene is something chemists usually consider settled science: bond order.

In the classroom, bond orders are clean and simple. A single bond has a bond order of 1. A double bond is 2. A triple bond is 3. These numbers reflect how many pairs of electrons are shared between atoms, and they shape how molecules behave.

But in these cage-shaped molecules, the math refuses to stay tidy.

Because of their extreme three-dimensional distortion, the double bonds in cubene and quadricyclene behave less like classic alkenes. Computational studies by Garg’s team and his longtime collaborator Ken Houk show that these bonds have a bond order closer to 1.5 than to 2. They are not quite single bonds, not quite double bonds, but something in between.

For a field that thrives on categories, this is deeply unsettling in the best possible way.

“Having bond orders that are not 1, 2 or 3 is pretty different from how we think and teach right now,” Garg said. It is a quiet admission that chemistry, as it is taught, may be a simplified map of a far more rugged landscape.

Molecules That Exist Only for a Moment

Cubene and quadricyclene are not molecules you can bottle, store, or even see directly. They are highly strained and unstable, appearing briefly before transforming into something else. Yet their existence is not speculative or imagined.

The team created stable precursor molecules decorated with silyl groups, which contain a silicon atom at their center, and carefully placed leaving groups. When these precursors were treated with fluoride salts, the reactions triggered the sudden formation of cubene or quadricyclene inside the reaction vessel.

Almost as soon as they formed, these fleeting molecules were intercepted by another reactant, locking their unusual structures into more stable, complex products. These products carry the fingerprints of cubene and quadricyclene’s brief lives, providing experimental evidence that the molecules truly existed, even if only for an instant.

The reactions happened with surprising speed. The researchers believe this is because the distorted, hyperpyramidalized carbons are under enormous strain. Like a compressed spring, the molecules are eager to react, releasing their tension through rapid chemical transformations.

Why Chemists Looked Away for So Long

What makes this work especially remarkable is not just what was discovered, but how long it was avoided.

Decades ago, chemists predicted that alkene-like molecules with these unusual shapes should be possible. The theory was there. The math supported it. Yet the molecules remained largely unexplored.

The reason, Garg suggests, lies in the power of tradition.

“We’re still very used to thinking about textbook rules of structure, bonding and reactivity in organic chemistry,” he said. As a result, molecules like cubene and quadricyclene were quietly set aside, labeled too strange or too impractical to pursue.

This new work challenges that mindset head-on. It suggests that many of chemistry’s most sacred rules should be treated not as laws, but as guidelines, useful but flexible, reliable but not inviolable.

A Shift Toward a More Three-Dimensional Future

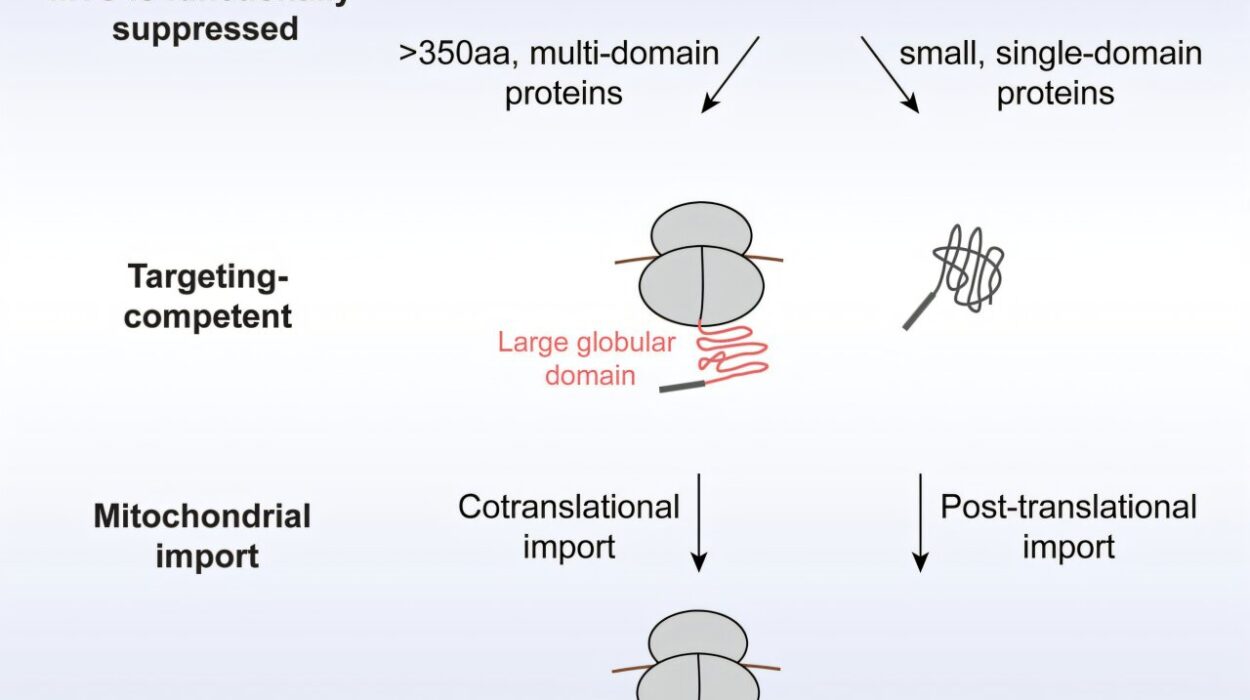

The timing of this discovery is no accident. Chemistry, especially medicinal chemistry, is undergoing a quiet transformation.

For much of the 20th century, drug molecules tended to be relatively flat. These shapes were easier to design, easier to make, and easier to understand. But over time, researchers have begun to exhaust the possibilities of these simpler structures.

Today, there is growing interest in rigid, three-dimensional molecules that occupy space in more complex ways. Such shapes open new possibilities for how medicines interact with biological systems.

“Making cubene and quadricyclene was likely considered pretty niche in the 20th century,” Garg said. “But nowadays we are beginning to exhaust the possibilities of the regular, more flat structures.”

Cubene and quadricyclene represent more than chemical curiosities. They are proof that chemistry can reach into previously inaccessible regions of molecular shape, creating structures that were once thought impractical or impossible.

A Laboratory Built on Curiosity and Courage

Behind this work is a lab culture that encourages questioning, creativity, and a willingness to challenge authority. Garg’s approach to chemistry emphasizes pushing fundamentals, pursuing practical value, and training students to think boldly about what molecules can be.

That philosophy has made his organic chemistry courses among the most popular at UCLA and has shaped the careers of students and postdoctoral scholars who now contribute to discoveries like this one. The study itself includes contributions from Jiaming Ding, Sarah French, Christina Rivera, Arismel Tena Meza, Dominick Witkowski, and computational insights from Ken Houk.

It is a reminder that scientific breakthroughs are rarely solitary acts. They emerge from teams willing to ask uncomfortable questions and explore ideas that do not fit neatly into existing frameworks.

Why This Discovery Truly Matters

At first glance, cubene and quadricyclene might seem like intellectual experiments, beautiful but impractical. After all, they cannot be isolated, and their existence is fleeting. But their importance runs deeper than their stability.

This research expands the very definition of what a chemical bond can be. It shows that bond orders can blur, geometries can warp, and molecules can exist in states that defy tidy classification. That expanded understanding gives chemists a larger creative toolkit.

For pharmaceutical science, this matters enormously. As drug discovery moves toward increasingly sophisticated three-dimensional structures, chemists need new ways to build complexity. The strategies developed to access cubene and quadricyclene could inspire entirely new classes of molecules, unlocking shapes and reactivities that were previously out of reach.

More broadly, this work is a powerful argument for scientific humility. Rules are essential, but they are not the final word. By questioning long-held assumptions, Garg’s team has shown that chemistry still holds surprises, waiting just beyond the edge of what we think we know.

In pushing the limits of structure and imagination, they remind us that progress often begins with a simple, daring thought: what if the rules are not as rigid as they seem?

Study Details

Ding, J., et al. Hyperpyramidalized alkenes with bond orders near 1.5 as synthetic building blocks. Nature Chemistry (2026). doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-02055-9