Prostate cancer is often described as the “slow-growing” cancer. For many men, especially those diagnosed with what is considered a low-grade form of the disease, the standard advice is simple: wait, watch, and monitor. This strategy, known as active surveillance, has spared thousands from unnecessary treatments and side effects. But a new study published in JAMA Oncology suggests that this wait-and-see approach may be riskier than previously believed—particularly for those diagnosed with Grade Group one (GG1) prostate cancer.

Led by researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine, University Hospitals Cleveland, and Case Western Reserve University, the study reveals that a significant number of men categorized as GG1 on biopsy—a diagnosis traditionally equated with low risk—may in fact harbor more aggressive cancers. And that, scientists warn, could spell trouble for patients and doctors alike.

Biopsy Blind Spots: The Limits of a Needle

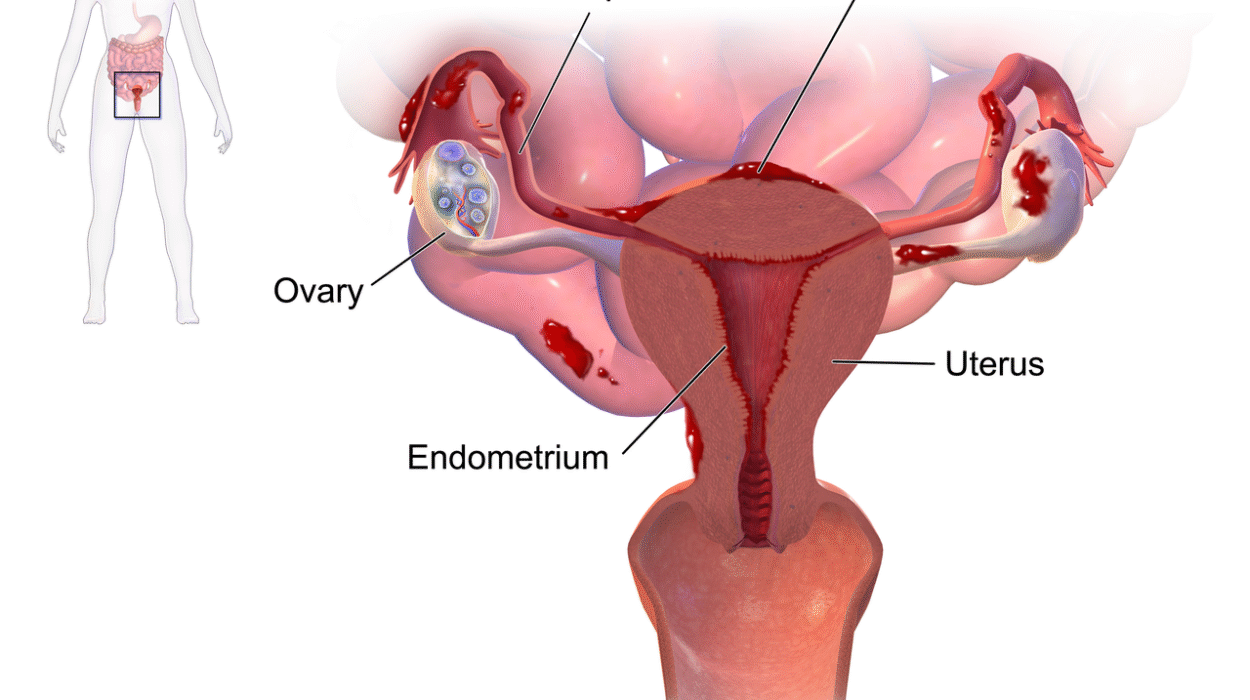

A biopsy, while crucial, offers only a sliver of insight. It samples tissue from small areas of the prostate, essentially taking a snapshot of a much larger landscape. What it can’t always do is expose the full truth.

“The challenge with prostate cancer,” explains co-senior author Dr. Bashir Al Hussein of Weill Cornell Medicine, “is that the disease can be heterogeneous. That means different areas of the prostate may contain different grades of cancer. If the biopsy only samples the lower-grade portion, it may miss more aggressive areas entirely.”

That’s exactly what the new study reveals. Drawing on data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program—an extensive, real-world cancer database—the researchers examined nearly 300,000 men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer between 2010 and 2020. Of those, roughly 117,000 had biopsy-confirmed GG1 tumors.

When researchers went beyond biopsy results and included other clinical factors—such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and tumor size—they found that one in six of these men were actually at intermediate or high risk. More than 18,000 patients in the GG1 group showed characteristics of cancers typically treated with surgery or radiation, not surveillance.

Not All “Low Grade” Means “Low Risk”

The discovery highlights a subtle but critical distinction: low grade is not always low risk. And that misunderstanding could be dangerous.

“There is a conflation happening in both the public and some medical discussions,” says Dr. Jonathan Shoag, associate professor of urology at Case Western Reserve University and co-senior author of the study. “People assume that a biopsy diagnosis of GG1 means the cancer is harmless. But our data shows that many of these patients actually face meaningful risks if left untreated.”

This growing confusion has led to calls from some experts to rename GG1 tumors—to remove the word “cancer” altogether. The idea is rooted in a desire to reduce patient anxiety and avoid overtreatment. After all, many GG1 tumors behave in a non-aggressive manner and may never cause harm.

But Shoag and his colleagues warn that such a change could cause more harm than good. “A name change might give patients a false sense of security,” he explains. “We found that around 30% of higher-risk patients were managed with active surveillance based on their GG1 biopsy, meaning they may have been undertreated.”

When Numbers Tell a Different Story

The study’s strength lies in the breadth and depth of its data. Unlike clinical trials, which may include only a narrow slice of the population, SEER captures a comprehensive picture of prostate cancer across the United States. It’s real-world data reflecting real-world decisions and outcomes.

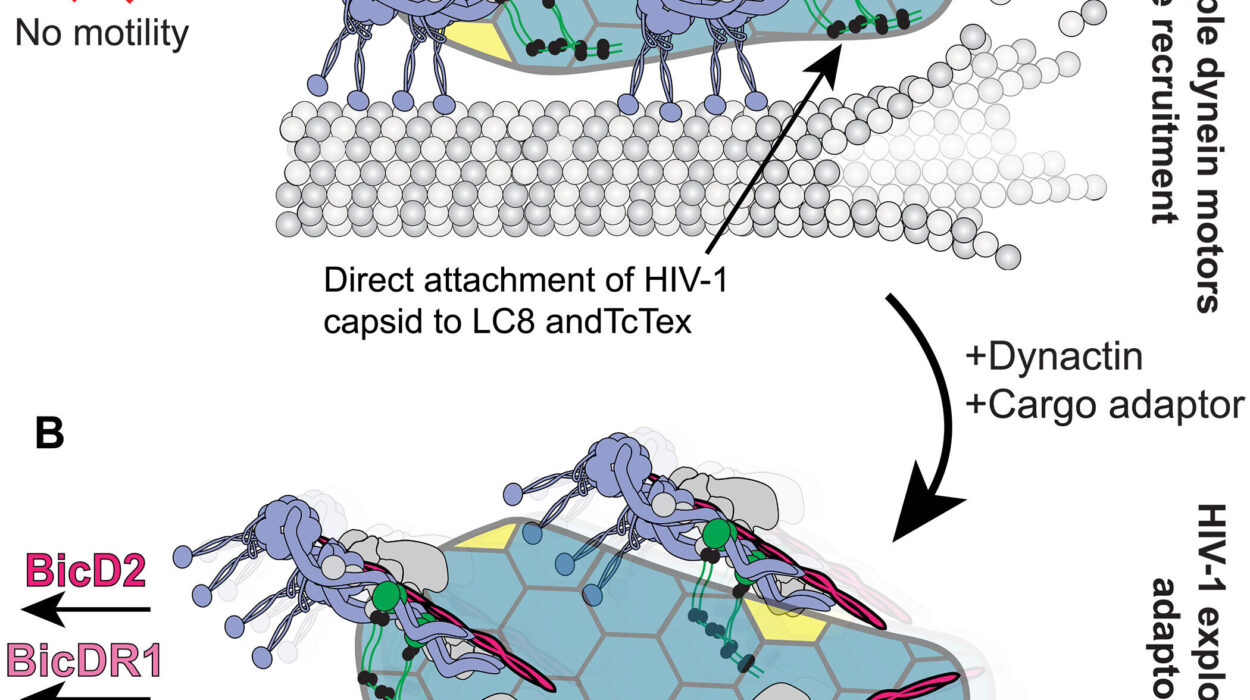

Lead author Dr. Neal Arvind Patel, a urologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, points out another key insight: the biology behind GG1 prostate cancer is more complex than once thought. “Some of these so-called low-grade tumors come with adverse clinical features. We need to study this biology more closely. It could lead us to a better understanding of which cancers are truly indolent and which ones just appear that way at first glance.”

One of the study’s major findings is that PSA levels—often used as a barometer for prostate cancer activity—can be misleading when interpreted in isolation. Some patients with low PSA and GG1 results still showed higher-grade disease when all factors were considered. It’s a reminder that cancer doesn’t always play by the rules.

A Better Way to Talk About Risk

If this new research reveals anything, it’s that physicians need to have more nuanced conversations with their patients. Risk isn’t binary. It exists on a spectrum, shaped by age, PSA levels, tumor volume, genetics, and biopsy results. Simply telling a man he has “low-risk” cancer may obscure the real danger.

“We need to change the way we talk to patients,” says Dr. Al Hussein. “Instead of using blanket terms, we should be offering a more personalized risk profile—explaining what the biopsy shows, what the imaging suggests, and what the PSA levels mean in context. Patients can handle complexity. What they can’t afford is misinformation.”

For now, the researchers advocate caution when interpreting GG1 results and urge both doctors and patients not to be lulled into a false sense of safety. Active surveillance remains a valid strategy for many men, but it must be guided by comprehensive clinical evaluation—not biopsy alone.

The Case Against Renaming

The debate over whether GG1 prostate cancer should still be called “cancer” is not just about semantics—it’s about strategy. Names carry weight. For better or worse, the word “cancer” activates concern, action, and often fear. Removing that word could lower patient anxiety, but it might also dissuade them from seeking follow-up care or second opinions.

“There’s this push to make the diagnosis less frightening,” says Dr. Shoag, “but fear, when paired with information, can lead to healthy decision-making. If we rename GG1, we risk encouraging complacency in men who actually need close monitoring—or even treatment.”

The issue is further complicated by how GG1 is defined. Biopsy results don’t always match the final pathology found after a prostate is surgically removed. In some cases, the cancer turns out to be more advanced than initially believed. That discrepancy is another reason experts say it’s premature to drop the term “cancer” from GG1 entirely.

A Call for Better Diagnostics

Ultimately, the study underscores a pressing need for improved diagnostic tools. The reliance on biopsy alone is insufficient. Advances in imaging, such as multiparametric MRI, and molecular testing may offer more accurate ways to predict cancer behavior and guide treatment.

“There’s real hope in emerging technologies,” says Dr. Patel. “But until those become standard practice, we need to be vigilant with the tools we have. That means using everything available—PSA tests, imaging, patient history, and clinical judgment—to make the best call for each individual.”

While the science evolves, the core message remains: even when a cancer appears quiet, it may be whispering warnings we can’t afford to ignore.

Looking Ahead: Personalized Prostate Cancer Care

The future of prostate cancer care likely lies in greater personalization. No longer can patients be categorized into neat boxes labeled “low-risk” or “high-risk” based solely on a biopsy. The human body is more nuanced than that.

Physicians are beginning to shift toward more holistic approaches—looking at patterns across the prostate, evaluating genetic predispositions, and incorporating artificial intelligence to detect early signals of progression. These innovations could help prevent both overtreatment and undertreatment, leading to better outcomes for all.

But until that future arrives, the study’s findings serve as a wake-up call.

“Biopsy is just the beginning,” says Dr. Al Hussein. “For some men, it’s the whole story. But for others, it’s only chapter one in a longer, more complicated narrative. We owe it to our patients to read the whole book before deciding what to do next.”