Celiac disease is a master of disguise. It lurks in the shadows of the digestive system, sometimes quietly, other times with a roar, sabotaging one of the body’s most essential functions—absorbing nutrients from food. It doesn’t arrive with fanfare, and it rarely causes immediate, dramatic symptoms that are easy to diagnose. Instead, it creeps in, a slow and steady destroyer of gut integrity. The story of celiac disease is one of betrayal—a betrayal by the very thing we rely on for sustenance: food.

At the heart of the problem is gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. For most people, gluten is harmless, nothing more than a structural protein that helps bread rise and gives pasta its chewy texture. But for those with celiac disease, gluten is poison. It sets off an immune response that attacks the lining of the small intestine, leading to widespread damage and a cascade of systemic consequences. The gut becomes a battlefield, and the consequences can affect every corner of the body.

The Role of the Small Intestine in Digestion

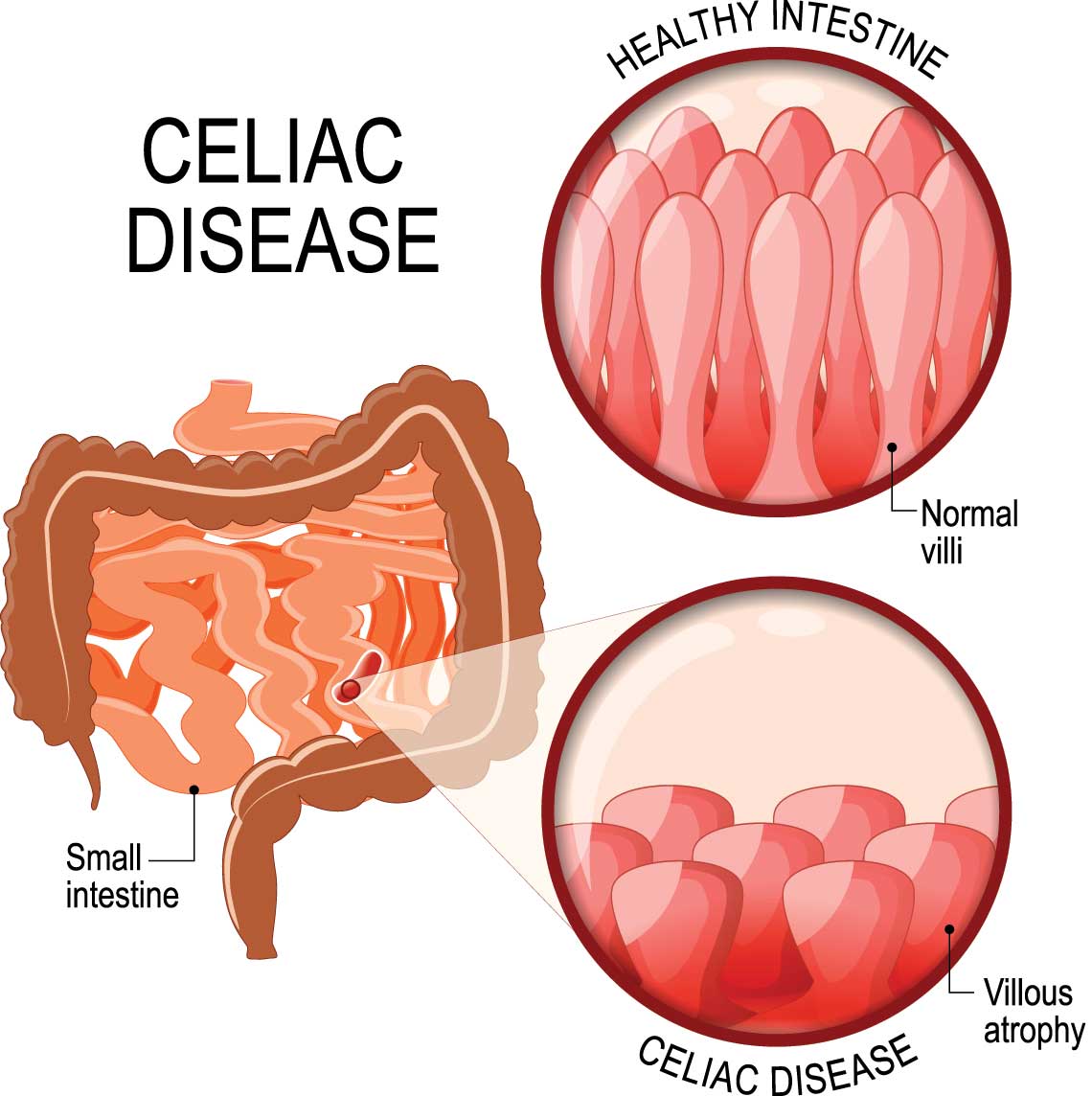

Before we can understand how celiac disease causes harm, we must appreciate the vital role of the small intestine in digestion. This organ is not just a simple tube where food passes through; it is a dynamic, highly specialized surface designed for absorption. Stretching about 20 feet long, the small intestine is lined with millions of finger-like projections called villi. These villi dramatically increase the surface area of the intestine, allowing for efficient absorption of nutrients such as carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals.

Each villus is covered with even tinier structures called microvilli, forming what’s known as the brush border. This dense layer of cellular structures is the final checkpoint in digestion, where nutrients are absorbed and passed into the bloodstream. It’s not just architecture—it’s a living, functional landscape, constantly renewing itself and responding to what we eat.

When functioning properly, the small intestine is a marvel of biological engineering. But in celiac disease, it becomes a victim of friendly fire. The very system that’s supposed to protect the body from invaders mistakes gluten for a dangerous enemy and begins an assault that leads to structural ruin.

Gluten: The Spark That Lights the Fire

Gluten itself is not inherently harmful. It is a complex of proteins, mainly gliadin and glutenin, that help form the elastic texture in dough. For someone with celiac disease, however, gluten becomes a dangerous trigger. The trouble starts with the digestion of gliadin, one of the protein components of gluten. As it passes through the stomach and enters the small intestine, fragments of gliadin resist complete breakdown by digestive enzymes. These fragments are small enough to be absorbed but still large enough to trigger an immune response in susceptible individuals.

The immune system, which should ignore harmless food proteins, instead sees these gliadin fragments as threats. This is partly due to a genetic predisposition found in most people with celiac disease—specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes, particularly HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8. These genes code for proteins that present gliadin to the immune system in a way that provokes an attack. This genetic setup essentially primes the body to overreact to gluten, misidentifying it as a foreign invader.

The Immune System’s Misguided Attack

Once the immune system is triggered by gliadin, it responds with a complex cascade of actions that cause inflammation and tissue damage. The body produces antibodies, such as anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and anti-endomysial antibodies, which are not only markers for diagnosis but also agents of destruction. These antibodies contribute to the damage by attacking the very tissue structures responsible for absorbing nutrients.

Tissue transglutaminase is an enzyme naturally found in the small intestine, where it plays a key role in repairing tissues and helping digest proteins. However, when gliadin enters the picture, tTG modifies gliadin in a process called deamidation. This modified gliadin is more likely to be recognized by the immune system, escalating the attack. The antibodies produced don’t just target gliadin—they also turn against tTG, a process that results in the erosion of the intestinal lining.

As the immune response intensifies, the villi in the small intestine begin to atrophy. They flatten and shrink, reducing the surface area available for nutrient absorption. This condition, known as villous atrophy, is the hallmark of celiac disease. The more extensive the villous atrophy, the more severe the malabsorption—and the more widespread the symptoms.

Malabsorption and Nutrient Deficiency

With the villi flattened and microvilli destroyed, the intestine becomes increasingly inefficient at absorbing nutrients. Even a diet rich in vitamins and minerals becomes meaningless if the gut cannot do its job. The consequences of malabsorption ripple outward, affecting every organ and tissue in the body.

Iron deficiency anemia is one of the most common signs of undiagnosed celiac disease. Without functional villi, the intestine struggles to absorb iron, leading to fatigue, weakness, and cognitive issues. Deficiencies in calcium and vitamin D can result in brittle bones, increasing the risk of fractures and osteoporosis even in young individuals. Lack of B vitamins, particularly B12 and folate, can contribute to neurological symptoms like tingling, numbness, and mood disturbances.

Protein-energy malnutrition can occur in severe cases, leading to muscle wasting, swelling from fluid imbalance, and impaired growth in children. Even fat absorption is compromised, leading to greasy, foul-smelling stools and deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K. The body begins to fail in subtle ways at first, then more dramatically, as it is starved of the building blocks it needs to function.

A Wide Array of Symptoms, Often Misunderstood

Celiac disease is known for being a medical chameleon. While some people experience classic gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, bloating, gas, and abdominal pain, many others present with entirely non-digestive complaints. This variability often leads to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

Some patients, especially children, may show signs of failure to thrive, developmental delays, or behavioral problems. Others may suffer from migraines, skin rashes like dermatitis herpetiformis, fertility issues, or even psychiatric symptoms like depression and anxiety. The unifying factor behind these diverse symptoms is damage to the gut and the resulting nutrient malabsorption.

The immune response itself also contributes to the wide-ranging effects. The inflammatory process triggered by gluten doesn’t stay confined to the intestines. Cytokines and immune cells circulate through the bloodstream, creating low-level inflammation throughout the body. This chronic, systemic inflammation may be subtle, but over time it wears down tissues, contributes to fatigue, and plays a role in associated autoimmune conditions.

The Connection Between the Gut and the Brain

One of the more fascinating and troubling aspects of celiac disease is its impact on the brain. Cognitive impairment, often described as “brain fog,” is a common complaint among those with active disease. Patients report difficulty concentrating, memory lapses, and mental fatigue. These symptoms often improve on a gluten-free diet, suggesting a direct connection between intestinal health and brain function.

This gut-brain connection is thought to be mediated by immune and inflammatory processes. When the gut lining is damaged, it becomes more permeable—a condition sometimes called “leaky gut.” This allows inflammatory molecules and partially digested proteins to enter the bloodstream and potentially reach the brain, where they can influence mood and cognition.

Neurological complications such as ataxia (a movement disorder), neuropathy (nerve pain), and even seizures have been linked to celiac disease. In many cases, these symptoms precede any gastrointestinal signs, further complicating the diagnostic process. The gut, it turns out, speaks volumes to the brain—and when the message is one of inflammation and dysfunction, the brain listens.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis: The Skin’s Cry for Help

In some individuals, the damage caused by gluten exposure shows up not just in the gut, but on the skin. Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an intensely itchy, blistering rash associated with celiac disease. It commonly appears on the elbows, knees, buttocks, and scalp and is often mistaken for eczema or another skin condition.

What makes DH especially telling is that it is caused by the same autoimmune mechanism that damages the gut. The body produces antibodies to tissue transglutaminase, which then cross-react with a related enzyme in the skin. The result is a rash that may look purely dermatological but is rooted in the same gluten-driven immune dysfunction. Even in patients who don’t experience digestive symptoms, DH can be a clear indicator of underlying celiac disease.

The Only Cure: A Lifelong Commitment

Unlike many autoimmune diseases, celiac disease has a known trigger and a clear treatment—complete removal of gluten from the diet. This is both a blessing and a burden. On one hand, there is no need for immunosuppressive drugs or risky surgeries. On the other, gluten is ubiquitous in modern diets and food processing. The commitment to a gluten-free diet must be lifelong, rigorous, and meticulously maintained.

Even trace amounts of gluten—crumbs on a cutting board, hidden ingredients in sauces—can cause an immune response and renew intestinal damage. The healing process can be slow, taking months or even years for the gut to fully recover. Children often heal faster than adults, but the road to recovery is rarely linear.

Despite the challenges, adherence to a gluten-free diet can lead to dramatic improvements in symptoms and quality of life. Villi can regenerate, nutrient levels can normalize, and systemic inflammation can decrease. But the vigilance must remain constant. There is no tolerance level for gluten in someone with celiac disease; the body remembers, and it reacts.

Long-Term Consequences of Unmanaged Disease

When celiac disease goes undiagnosed or untreated, the long-term consequences can be severe. Chronic malabsorption can lead to serious complications including infertility, neurological decline, osteoporosis, and increased risk for certain types of cancer, particularly intestinal lymphoma. The constant immune activation takes a toll, wearing down tissues and weakening resilience.

Even among those who have been diagnosed, the risk remains if dietary vigilance lapses. Some patients develop refractory celiac disease, a rare but serious form that does not respond to a gluten-free diet and may require immunosuppressive therapy. For these individuals, the damage becomes so entrenched that the immune system continues to attack the intestine even in the absence of gluten.

Hope on the Horizon

Research into celiac disease continues to evolve. Scientists are exploring therapies that could allow people with celiac disease to tolerate small amounts of gluten without triggering an immune response. Enzyme supplements, vaccines, and drugs that block the immune cascade are all under investigation. While none of these treatments have yet replaced the gluten-free diet, they offer hope for a future where dietary restrictions are less burdensome.

More importantly, increased awareness and improved diagnostic tools are leading to earlier recognition of the disease. Blood tests that measure specific antibodies, followed by intestinal biopsies, can confirm a diagnosis with increasing accuracy. Genetic testing can help rule out the disease in those who do not carry the associated HLA genes.

A Personal Journey Toward Healing

Living with celiac disease means learning to navigate a world that was not designed with your body in mind. It requires reading every label, asking every server, educating friends and family, and constantly advocating for yourself. But it also means understanding your body in a profound way. You learn to respect its signals, to listen when it whispers rather than waiting for it to scream.

With time and support, many people with celiac disease not only recover their health but also develop a stronger relationship with their bodies and their food. The disease demands discipline, but it also offers clarity—a knowledge of what your body needs and what it cannot tolerate.

Celiac disease damages the gut, yes. But with understanding, treatment, and care, that damage can be healed. The gut, like the body as a whole, has an extraordinary capacity for regeneration. And that, perhaps, is the most important lesson of all.