They say the eyes are the windows to the soul. But according to new research, they may also be windows into the health of the brain. Scientists have long known that memory and attention leave subtle footprints in the way we move our eyes, but a new multi-institution study has shown just how powerful those footprints can be.

A team of researchers from Canada and the West Indies reports that simple gaze patterns—where we look, how often we shift our focus, and how consistently we return to the same spots—may serve as an early and sensitive marker of cognitive decline. The findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), suggest that eye-tracking could help identify memory problems years before more obvious symptoms appear.

Why Eye Movements Matter

When we look at the world, our eyes do far more than capture images. Each glance, each flicker of attention, reflects the brain’s work of encoding and retrieving information. In healthy young adults, the eyes wander widely and flexibly, sampling many different features of a scene. This kind of exploratory scanning helps the brain build a rich, detailed memory of the environment.

But as memory function declines with age or disease, the pattern shifts. The eyes become less adventurous, revisiting the same spots again and again. Instead of layering new details into memory, the brain begins to rely on fewer cues, leading to weaker, less complete recollections.

That connection—between memory function and viewing behavior—has been observed before. But this new study goes further, showing that multiple gaze features taken together, rather than a single measure, provide a powerful picture of cognitive health.

Inside the Study

To probe the link between memory and gaze, researchers ran two large experiments with more than 170 participants divided into five groups: young adults, healthy older adults, older adults at risk of cognitive decline, individuals diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and individuals with amnesia.

Each participant wore a head-mounted eyetracker while viewing hundreds of images—ranging from animals to landscapes to everyday objects. Some images were novel, while others were repeated across viewing sessions. Importantly, participants were not asked to remember anything. They simply looked at the images, allowing their natural eye movements to tell the story.

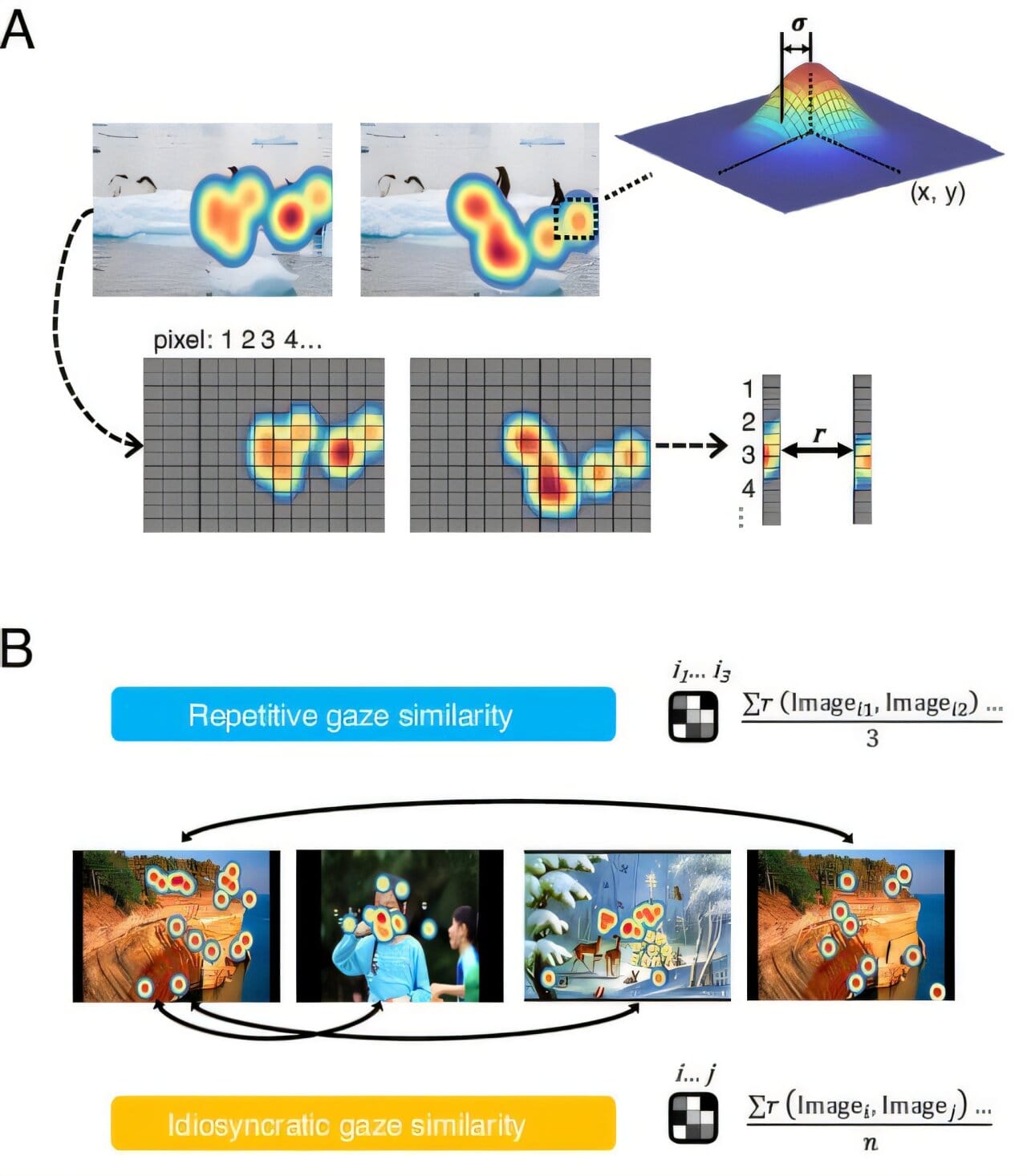

The team then analyzed the gaze data using sophisticated statistical models. They looked at three key factors:

- Idiosyncratic gaze similarity – how consistently a participant’s eyes landed on the same features of different images.

- Fixation count – how many distinct points the eyes fixated on.

- Fixation dispersion – how widely the eyes roamed across an image.

What the Eyes Revealed

The results were striking. Idiosyncratic gaze similarity steadily increased as memory function declined. Young adults showed the least similarity—meaning they explored each image in unique ways—while individuals with amnesia showed the highest similarity, often locking onto the same limited details again and again.

Fixation dispersion also decreased with memory impairment, showing a clear drop in explorative scanning. Interestingly, fixation count rose slightly across groups, but this change was not strong enough to be considered reliable.

In the second experiment, where some images were repeated, the pattern was even clearer. Young adults shifted their gaze with each presentation, encoding fresh details and strengthening their memory of the image. In contrast, those with memory impairments tended to view the same features repeatedly, a strategy that reinforced weak or incomplete memory traces.

Why It Matters

These findings go beyond academic curiosity. They suggest that naturalistic gaze patterns—measured during simple, everyday viewing tasks—can serve as sensitive, non-invasive markers of memory decline. Unlike complex medical tests, eye-tracking is relatively easy and inexpensive, opening the door to new screening tools for conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

Even more importantly, the results highlight what may be happening in the brains of people with memory impairments. Instead of building new, detailed representations, their encoding strategies fall back on repetition and redundancy. Over time, this leads to “impoverished memory representations,” or weaker memories that fade more easily.

Toward the Future of Early Detection

Imagine a future where a routine eye exam could do more than check vision—it could also screen for early signs of memory decline. The technology already exists. Eyetrackers are widely used in psychology labs and are becoming increasingly affordable. What studies like this show is that with the right analysis, they could become powerful tools for brain health monitoring.

For families and clinicians, this could mean earlier detection of conditions like mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease, when interventions may be most effective. For researchers, it provides a new, objective way to study how memory works and why it falters.

The Eyes as Silent Witnesses

Albert Einstein once said, “The important thing is not to stop questioning.” In a way, our eyes are always questioning the world—seeking details, patterns, and meaning. As this study reveals, the way we look tells a hidden story about how well our memory is functioning.

Far from being passive windows, our eyes are active narrators of our cognitive health. And now, science is learning to listen to what they have to say.

More information: Jordana S. Wynn et al, Decoding memory function through naturalistic gaze patterns, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2505879122