Fourteen thousand years ago, long before maps or borders or even names for continents, a group of people paused in what is now Alaska. They lit fires. They worked stone. They shaped ivory taken from a mammoth tusk. When they moved on, they left behind fragments of their lives, pressed quietly into the soil.

For thousands of years, the land kept their story hidden.

Now, stone flakes, ivory tools, and layers of earth are beginning to speak again. At a site called Holzman, tucked within Alaska’s Tanana Valley, researchers have uncovered evidence that may bring us closer than ever to understanding who the first people in the Americas were and how their journey unfolded.

This story does not announce itself with certainty or grand declarations. Instead, it emerges slowly, layer by layer, from the ground itself, revealing a moment of transition, a technological inheritance, and a culture on the move.

The Long Debate Over First Footsteps

For decades, the story of the first Americans seemed almost settled. The Clovis people, identified by their distinctive stone tools, were long thought to be the continent’s earliest inhabitants. Their appearance around 13,000 years ago became a cornerstone of archaeological understanding.

But science rarely stays still. Over time, discoveries from different parts of the Americas began to challenge that timeline, suggesting that humans may have arrived thousands of years earlier. The debate widened, becoming less about a single culture and more about routes, adaptations, and deep time.

Into this debate steps new evidence from Alaska, published in the journal Quaternary International. Rather than overturning existing ideas outright, it does something more subtle and powerful. It suggests a connection. A bridge not just of land, but of knowledge.

Crossing a Lost World Called Beringia

To understand why Alaska matters so deeply in this story, one must picture Beringia, a vast land bridge that once linked Siberia to North America. During a time when sea levels were lower, this expanse allowed people to walk between continents, carrying their tools, skills, and traditions with them.

As these early hunters moved eastward, they did not rush blindly forward. They settled where conditions allowed, favoring ice-free regions of Alaska where resources could sustain them. The Tanana Valley was one such place, and the Holzman site appears to have been one of their stopping points.

What they left behind was not a single snapshot, but a sequence. Layers of soil that captured moments separated by centuries, preserving traces of changing behavior and evolving technology.

A Mammoth Tusk in the Deepest Layer

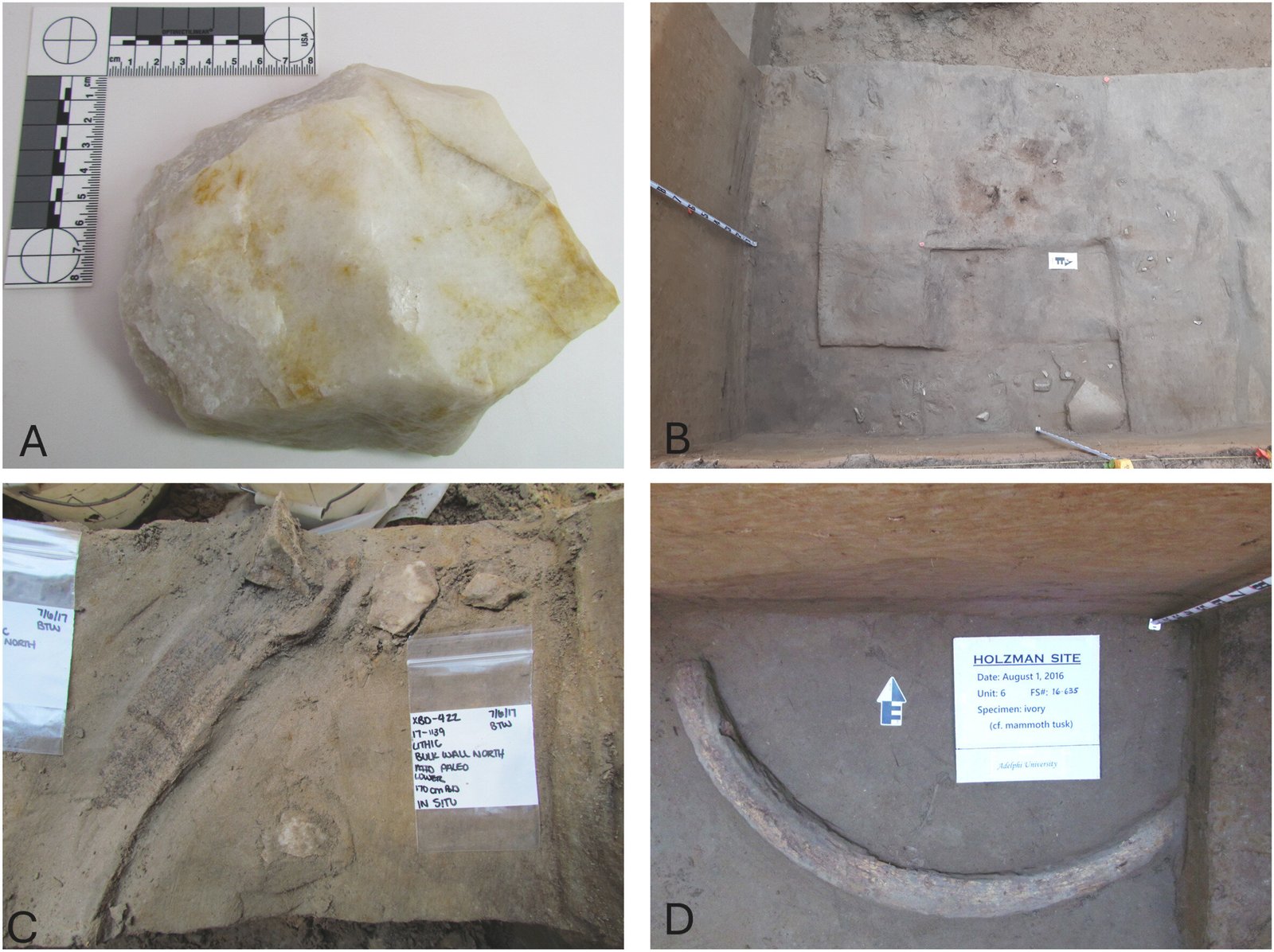

The deepest layer at the Holzman site reaches back 14,000 years. In this ancient stratum, researchers found something remarkable: a nearly complete mammoth tusk, resting alongside the remains of campfires and scattered stone flakes.

This combination tells a quiet but vivid story. Fire suggests warmth, food preparation, and social life. Stone flakes point to tool-making. The mammoth tusk hints at hunting, scavenging, or the careful use of massive animals that once roamed the region.

This layer does not yet reveal finely shaped tools or elaborate craftsmanship. Instead, it captures a moment of presence. People were here. They worked. They survived.

Then, just above this layer, time shifts slightly forward, and the story deepens.

The Workshop That Changed the Conversation

Dating to 13,700 years ago, the layer above contains evidence that has drawn particular attention from researchers. Here, they found what appears to be a workshop, a place where quartz was used to carve ivory rods.

These rods are not just old. They are the earliest known examples of their kind in the Americas.

What makes them truly compelling is not their age alone, but how they were made. The carving techniques used on these ivory rods closely match those associated with the Clovis people, who would appear a few centuries later.

This detail transforms the rods from isolated artifacts into messengers. They suggest that the methods later seen in Clovis culture did not appear suddenly or independently. Instead, they may have been inherited.

Technology That Traveled With People

According to the researchers from Adelphi University and the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the tools at Holzman point to a population that did not remain in one place. These people carried their knowledge with them, passing it down as they moved.

The ivory rods, shaped with precision, reflect learned techniques. Stone tools show continuity rather than reinvention. Together, they suggest a cultural thread stretching from eastern Beringia into regions farther south.

In the researchers’ words, mammoth ivory and lithic material appear to have played an important role in how resources and technologies circulated across the landscape, eventually accompanying people as they dispersed toward the Rocky Mountains and the Northern High Plains of North America.

This was not a single migration event frozen in time. It was a process. A slow unfolding of movement, learning, and adaptation.

Not the First, but a Missing Link

The findings at Holzman do not claim that these Alaskan pioneers were the first humans to enter the Americas. Nor do they argue that Clovis culture emerged entirely from this single site.

What they offer instead is a missing link. Evidence that helps explain how Clovis technology could have developed from earlier traditions rather than appearing abruptly.

By placing Clovis-style carving techniques at 13,700 years ago, before the recognized emergence of Clovis culture around 13,000 years ago, the site provides a plausible technological ancestry.

It suggests continuity where there was once a gap.

What the Earth Still Has Yet to Say

As compelling as these discoveries are, the researchers themselves acknowledge that the story is not finished. Stone tools and ivory can tell us much, but they cannot answer every question.

Further work involving ancient DNA and climate patterns may eventually provide stronger confirmation of who these people were and how they adapted to changing environments.

For now, the evidence rests in the ground, waiting for science to ask the next careful question.

Why This Story Matters Now

This research matters because it reshapes how we think about human beginnings in the Americas. Instead of a single cultural starting point, it reveals a deeper narrative of movement, inheritance, and continuity.

The people at the Holzman site were not isolated innovators or accidental wanderers. They were part of a living tradition, carrying skills across generations and landscapes. Their tools show intention. Their camps show planning. Their legacy suggests connection.

By illuminating the transition from Beringian hunters to Clovis culture, this work helps humanize a journey that can otherwise feel abstract and distant. It reminds us that the peopling of the Americas was not just a matter of dates and routes, but of people adapting, teaching, and remembering as they moved through a changing world.

Fourteen thousand years later, their story is still unfolding. And with every layer uncovered, the ground beneath Alaska brings us a little closer to understanding where we come from.

Study Details

Brian T. Wygal et al, Stone and mammoth ivory tool production, circulation, and human dispersals in the middle Tanana Valley, Alaska: Implications for the Pleistocene peopling of the Americas, Quaternary International (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2025.110087