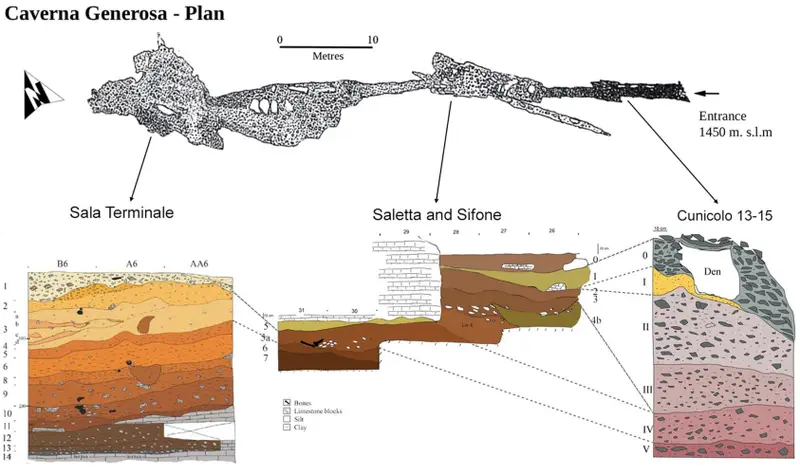

The cave sits quietly at 1,450 meters above sea level, carved into the Italian Alps where the air thins and the weather turns quickly. Today it is known as Caverna Generosa, a place long associated with bears. For years, researchers have pulled hundreds of bear skeletons from its depths, their bones layered like memories of winters long past. But hidden among teeth and fractured ribs, something else waited in silence. Sixteen small stone tools, weathered and altered by time, whispered of visitors who were not animals at all.

This high-altitude shelter was never meant to be permanent. It was not a village, not a home, not even a campsite in the usual sense. Yet the presence of those tools suggests something quietly remarkable. Long before modern maps or climbing gear, Neanderthals passed through this unforgiving landscape, climbing into the mountains and stepping into bear caves as part of a carefully planned journey.

The Unexpected Company of Stone and Bone

When archaeologists first noticed the stone artifacts among the bear remains, the discovery raised immediate questions. Bears had clearly used the cave repeatedly, likely returning year after year. But humans leave different traces, and these traces were scarce. Only 16 tools emerged from the cave, scattered rather than clustered, worn rather than fresh.

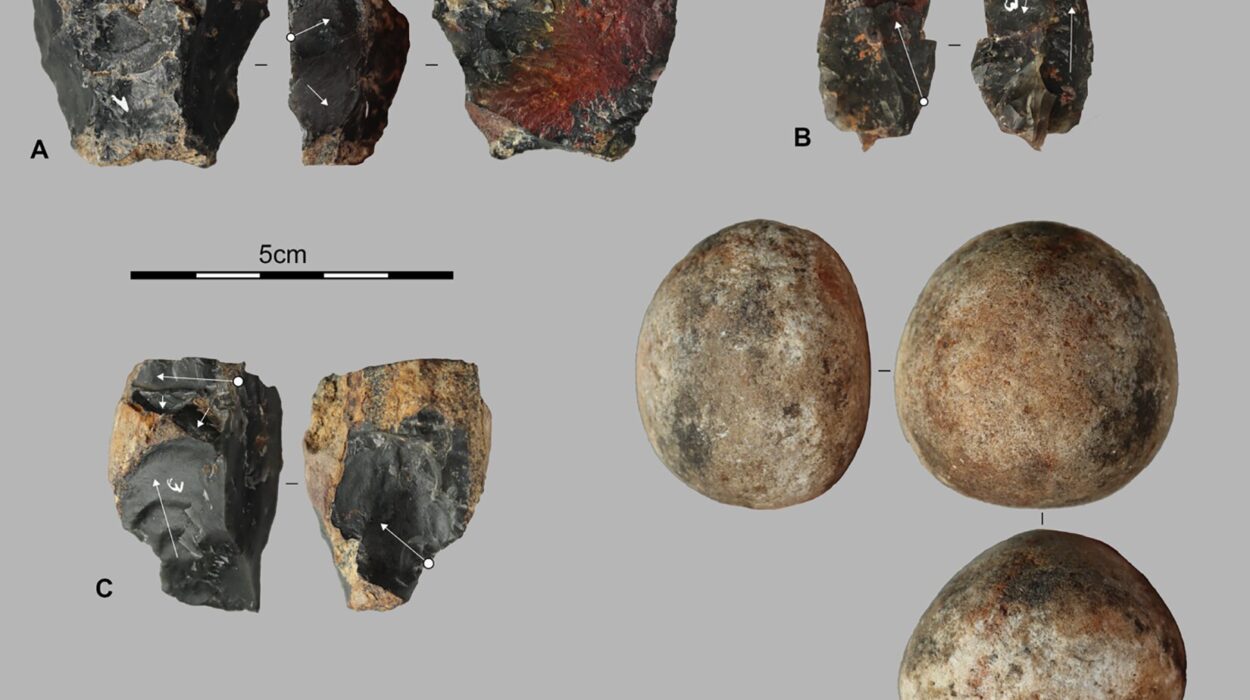

The new study, published in the Journal of Quaternary Science, focused on understanding what these tools were doing so high in the mountains. The researchers examined them closely, looking not just at their shape, but at their chemistry, their damage, and the subtle marks along their edges. What they found suggested that these objects were not accidents, and they were not leftovers from a long stay.

They were carried there on purpose.

Tools That Traveled

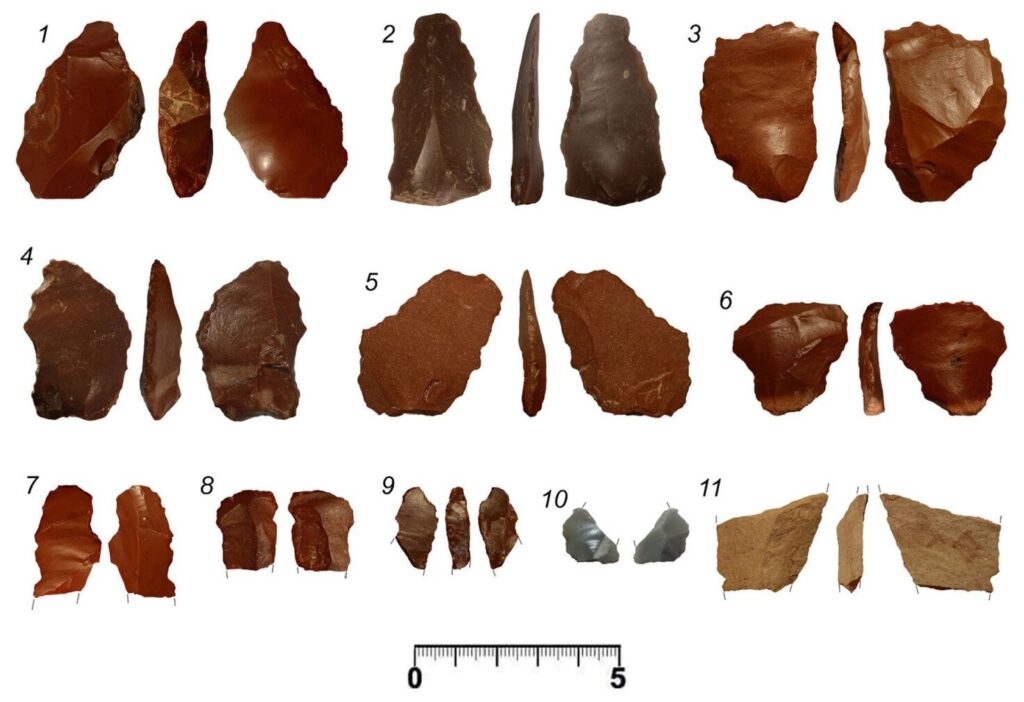

One of the first clues came from what was missing. There were no stone flakes, no chips, no debris from tool-making. This meant the tools were not created inside the cave. Instead, they arrived already finished, tucked into whatever passed for a Neanderthal backpack.

Chemical analysis revealed where they came from. The stones were made of high-quality flint and radiolarite, materials not found near the cave itself. Their source lay a few kilometers away and much lower down the mountain. Whoever carried them had climbed with intention, bringing carefully chosen tools upward into a harsh and unpredictable environment.

These were not casual objects picked up along the way. They were part of a plan.

Edges That Tell a Story

Under high-powered microscopes, the tools revealed another layer of their history. Along their edges were clear retouch marks, signs that the tools had been resharpened again and again. This kind of maintenance suggests long-term use, not disposable gear.

In a place where making new tools was impossible, the ones brought along had to last. The repeated sharpening shows foresight. These travelers expected to rely on their tools for the duration of their journey. They knew where they were going, and they knew what they would need once they got there.

Most of the artifacts were identified as Levallois products, made using a specific prehistoric stone-working method. Their presence reinforces the idea that these were not random objects, but carefully selected pieces of a mobile toolkit, designed for flexibility and endurance.

A Stop Along the Way, Not a Home

The researchers describe Caverna Generosa as a place of “episodic passage.” The phrase captures the spirit of the site perfectly. Everything about the cave points away from long-term living. The extremely low number of artifacts, their altered condition, and the absence of manufacturing debris all suggest brief visits rather than settlement.

This was a refuge, not a residence. A pause in the journey. A place to shelter, perhaps to work briefly, then to move on.

Neanderthals were not carving out a life here. They were passing through.

Sharing Space With Giants

The cave’s most dominant residents were bears. The sheer number of bear skeletons makes that clear. These animals likely used the cave for hibernation, returning season after season. The Neanderthals, however, probably timed their visits carefully.

The researchers suggest that humans most likely entered the cave during the summer months, when bears were away. Living alongside hibernating giants would have been dangerous and unnecessary. Still, the overlap in space raises intriguing possibilities.

Although detailed wear analysis was not possible due to the tools’ poor condition, similar tools found in other bear caves have been linked to animal processing. This opens the possibility that Neanderthals hunted bears or scavenged those that had died during hibernation. The cave may have offered both shelter and opportunity, though never comfort.

Travelers With a Plan

Much of what we know about Neanderthals comes from valley settlements, places where people stayed long enough to leave deep archaeological footprints. Caverna Generosa tells a different story. It speaks of movement rather than permanence, of routes rather than roots.

These Neanderthals were capable of planning trips through challenging terrain. They selected durable tools, sourced materials from far below, maintained their equipment, and timed their movements with the seasons. They understood the mountains well enough to navigate them, and they prepared for what awaited them along the way.

This was not wandering. It was strategy.

Why This Discovery Changes the Picture

The significance of this research lies not in the number of tools, but in what they reveal about Neanderthal behavior. The findings show that Neanderthals were not limited to comfortable environments or simple routines. They moved through high-altitude landscapes with purpose and preparation.

By studying a cave that was never meant to be home, scientists have gained insight into how Neanderthals thought ahead, managed resources, and adapted to demanding journeys. These travelers were skilled planners, capable of organizing mobile toolkits and using temporary shelters to extend their reach into difficult terrain.

Caverna Generosa reminds us that intelligence is not always loud or obvious. Sometimes it appears quietly, in a handful of worn tools left behind in a bear cave high above the valleys below.

Study Details

Davide Delpiano et al, Neanderthal incursions at a high‐altitude “bear cave”: Reassessing Caverna Generosa in the southern Alps, Journal of Quaternary Science (2026). DOI: 10.1002/jqs.70048