At the Chaparabad archaeological site in Iran, a ceramic vessel once used for cooking was quietly holding a far more delicate history. Buried inside it was a fetus, preserved so completely that nearly 90 percent of the tiny bones survived the long passage of time. Dated to the mid-5th millennium BC, this burial, known as L522.1, is now recognized as one of the most complete prehistoric infant burials ever found on the Iranian plateau. Just a few steps away, less than three meters apart, another fetal burial lay waiting, similar in age yet profoundly different in treatment. Together, these two silent graves are reshaping how archaeologists think about life, loss, and care in prehistoric southwestern Asia.

The study, conducted by Dr. Mahdi Alirezazadeh and Dr. Hanan Bahranipoor and published in Archaeological Research in Asia, focuses not only on what was found, but on what these remains can tell us about the emotional and cultural choices made by people thousands of years ago. These were not abstract rituals. They were intimate decisions made in domestic spaces, in kitchens and storage rooms, among vessels that once simmered meals for the living.

Two Tiny Lives, Buried Side by Side but Worlds Apart

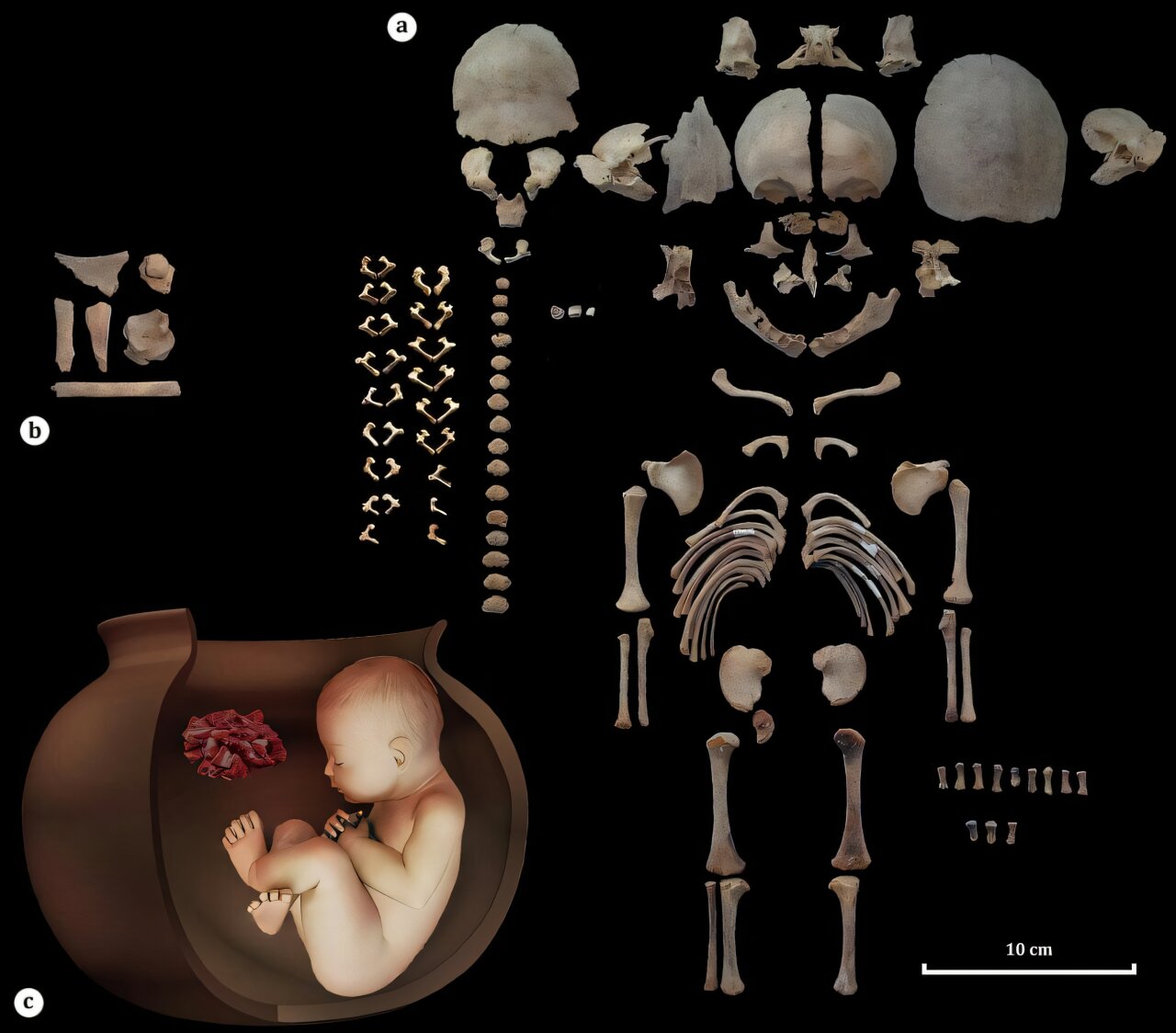

The two burials, labeled L522.1 and L815.1, were uncovered during excavations between 2021 and 2023. Both were fetal vessel burials, meaning the remains were placed inside ceramic containers. Both vessels belonged to the Dalma culture, dating to the early 5th millennium BC, and both had been used in everyday domestic life before becoming burial containers.

Yet despite these similarities, the differences are striking. L522.1 was found inside structure D, interpreted as a kitchen. The vessel holding the fetus was a Red Slip Ware, a well-known ceramic type of the Dalma tradition. Smoke staining on its outer surface revealed that it had once sat over a fire, cooking meals before being repurposed for burial.

L815.1, in contrast, was buried in what archaeologists believe was a storage space. No grave goods accompanied this fetus. The vessel itself offered no additional items, no animal remains, no worked objects. The burial was simple, quiet, and unadorned.

These differences immediately raised questions. Why were two fetuses, buried so close together and during the same time period, treated so differently?

Inside the Bones, a Final Moment Preserved

The exceptional preservation of L522.1 allowed researchers to look closely at the skeletal remains. By examining bone fusion and long bone lengths, the team estimated that both fetuses died between 36 and 38 weeks of gestational age. They were, by biological standards, near full term.

No signs of violence or deliberate harm were found on the bones. There was, however, a fracture on the right parietal bone of L522.1, part of the skull. At first glance, this might seem alarming. But the context tells a gentler story. The fractured bone was located near the rim of the vessel, and the researchers concluded that soil pressure during or after burial likely caused the break. It was not a wound from life, but a consequence of time pressing down.

The bones of L815.1 were less complete, yet still informative. Together, the remains show that these fetuses were carefully placed, not discarded. Their burials were deliberate acts.

Gifts for One, Silence for the Other

What truly sets the two burials apart is the presence of grave goods. L522.1 was accompanied by ovicaprid remains, likely sheep or goat, placed both inside the vessel near the rim and beneath it. Nearby, archaeologists also found a worked stone, suggesting additional symbolic or practical meaning attached to the burial.

L815.1 received none of these items. No animal bones. No tools. No offerings.

Because the two burials were found within the same architectural space of approximately 310 square meters, and because both date to a time when the Dalma and Pisdeli cultures were active, the researchers could rule out simple explanations. This was not a matter of different cultural traditions or different time periods. Nor could it easily be explained by social rank or family status.

As Dr. Alirezazadeh explains, their proximity and shared chronology make these usual explanations unlikely. The variation, instead, seems to reflect something more nuanced and personal.

A Pattern of Difference Across Ancient Lands

What happened at Chaparabad is not an isolated case. Across southwestern Asia, fetal and infant burials from the Neolithic through the Chalcolithic periods show remarkable diversity. Some infants were buried with care and offerings, others with none. Some vessels were sealed with inverted bowls or ceramic fragments, others left open. Some burials included objects of stone or even metal, while others remained empty.

Examples from other sites illustrate this range. At Chagar Bazar in Syria, burial vessels ranged from weaning bowls to miniature pots. At Tell as-Sawwan, vessels were often sealed with inverted bowls and ceramic fragments. At Girdi Sheytan, a fetus was buried with stone beads. At Ovçular Tepesi, three copper axes were found alongside fetal remains. And at Yarim Tepe, near Dalma, all fourteen fetal burials contained no grave goods at all.

Chaparabad fits squarely into this broader picture of variability. The difference between L522.1 and L815.1 echoes choices seen across the region, suggesting that there was no single rule governing how fetal individuals were treated in death.

The Limits of Knowing, and the Care of Not Guessing

Despite the richness of the evidence, the researchers are careful not to overreach. They emphasize that archaeologists were not members of these prehistoric communities. They cannot know the personal circumstances, beliefs, or emotions that shaped each burial.

As Dr. Alirezazadeh notes, interpretations can only extend as far as the data allow. The presence or absence of grave goods may have reflected family decisions, ritual meanings, or circumstances surrounding each death. Without written records or living witnesses, certainty remains out of reach.

What can be said, however, is that fetal individuals were culturally significant. They were not ignored or treated as disposable. Their placement within domestic spaces and within vessels once used for daily life suggests a profound connection between the living household and the loss that occurred within it.

Looking Ahead, What These Tiny Graves May Still Tell Us

The story of these two burials is not finished. Ongoing DNA analysis and stable isotope studies may soon offer new insights into biological relationships, health, and maternal conditions. Each new method has the potential to add another layer to the narrative preserved in bone and clay.

For now, these discoveries stand as rare windows into prehistoric life. Fetal burials are seldom preserved so well, and even more rarely found so close together with such clear differences in treatment.

Why This Research Matters More Than It First Appears

At first glance, these burials might seem like small details in the vast sweep of human history. But they touch on something deeply universal. They show that even five thousand years ago, people grappled with loss before birth. They made choices about care, remembrance, and meaning. They placed fetal remains inside familiar household objects, embedding grief within the rhythms of daily life.

By studying L522.1 and L815.1, researchers are not just cataloging bones and pots. They are uncovering evidence of how prehistoric communities understood personhood, mourning, and the value of lives that barely had time to begin. The variability in burial practices reminds us that ancient cultures were not rigid or uniform. They were complex, responsive, and human.

In the quiet soil of Chaparabad, two tiny graves remind us that the past is not distant or cold. It is intimate. And sometimes, the smallest remains carry the heaviest stories.

Study Details

Mahdi Alirezazadeh et al, Fetal vessel burials dated to 6500 years ago at the Chaparabad archaeological site, Northwestern Iran, Archaeological Research in Asia (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.ara.2025.100682