For hundreds of thousands of years, wood has been humanity’s quiet accomplice. It shaped shelters, stirred fires, dug soil, and carried hands through daily work. Yet wood almost never survives long enough to tell its story. Stone does. Bone sometimes does. Wood usually vanishes without a trace. That is why two small, weathered fragments from a lakeshore in Greece have sent a ripple through the study of human origins. Against all odds, they endured, and in doing so, they changed what we know about the earliest tools held by human hands.

At a site called Marathousa 1, in Greece’s central Peloponnese, researchers have uncovered the earliest known hand-held wooden tools ever found. These objects were shaped and used by humans roughly 430,000 years ago, deep in the Middle Pleistocene, a time when our ancestors were beginning to experiment with more complex ways of living and interacting with their environment. The discovery pushes the evidence for such tools back by at least 40,000 years, extending the timeline of human ingenuity further into the past.

A Lakeshore Frozen in a Different World

Marathousa 1 was once the edge of a lake, a place where water met land and life gathered. Today, it preserves a snapshot of intense activity from a vanished world. Alongside the wooden finds, archaeologists uncovered stone tools and the remains of an elephant and other animals, clear signs that early humans used this lakeshore as a butchering site.

This was no quiet scene. The bones tell of large animals being processed. The stones speak of skilled hands capable of shaping sharp edges. And now, the wood adds another layer, suggesting that humans here were not limited to stone alone. They were reaching for plants, selecting specific trees, and shaping wood for particular tasks.

The research, published in PNAS, was jointly led by Professor Katerina Harvati of the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen and Dr. Annemieke Milks of the University of Reading, an expert in early wooden tools. Together with an international team, they followed the faintest clues left on the surface of ancient wood.

The Middle Pleistocene Turning Point

The period in which these tools were made matters deeply. The Middle Pleistocene, spanning roughly 774,000 to 129,000 years ago, marks a critical chapter in human evolution. According to Professor Harvati, it was during this time that more complex behaviors began to emerge, including the earliest reliable evidence for the targeted technological use of plants.

Stone tools from this era are well documented. Bone artifacts appear occasionally. But wood, despite likely being used every day, almost never survives. Its absence has long distorted our understanding, making early humans seem more limited than they truly were. The discoveries at Marathousa 1 help correct that imbalance.

The worked stones and bone artifacts already suggested a wide range of activities at the site. That realization prompted the team to look again at the wooden remains, not as natural debris, but as possible tools waiting to be recognized.

Reading the Scars Left by Ancient Hands

Wood does not announce itself as a tool. It whispers. To hear it, the researchers had to examine every surface with care. As Dr. Milks explains, wooden objects need exceptional conditions to survive over such immense timescales. At Marathousa 1, those conditions existed, preserving not just the wood itself, but also the marks left behind by its makers.

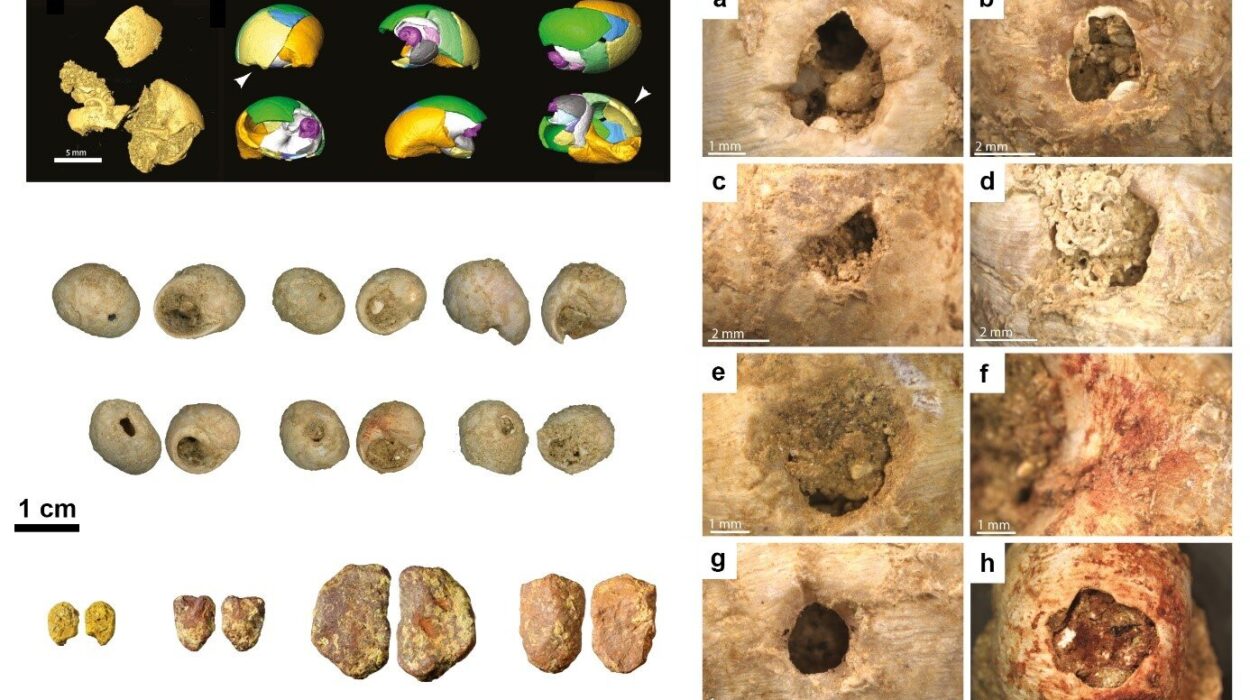

Under microscopes, the team studied the surfaces in detail. What they found were unmistakable signs of chopping and carving, patterns that do not occur through natural processes alone. Two objects stood out clearly as human-made.

One was a small piece of alder wood, part of a trunk that showed both deliberate shaping and signs of wear from use. Its edges and surfaces bore the subtle scars of repeated contact, suggesting it had been held, pressed, and worked against other materials.

The second object, even smaller, came from a willow or poplar tree. Though modest in size, it too carried evidence of working and possible use. Together, these pieces form the oldest known example of humans shaping wood to hold and use directly.

Tools for Life at the Water’s Edge

What were these tools used for? The evidence allows for careful interpretation, not speculation. The alder tool, worn and shaped, was likely used for digging at the edge of the lake or removing tree bark. These are tasks closely tied to survival, whether for accessing edible plants, processing materials, or maintaining tools and shelters.

The setting reinforces this idea. A lakeshore offers soft ground, plant resources, and opportunities for repeated activity. A wooden digging tool would have been both practical and efficient, easy to make, easy to replace, and well suited to the environment.

The second wooden piece, smaller and more fragmentary, shows signs of working but leaves its exact function open. What matters is not the specific task, but the broader implication. These early humans were choosing particular types of wood and modifying them intentionally.

Separating Human Work from Animal Marks

Not every wooden fragment at Marathousa 1 turned out to be human-made. A third piece, a larger section of alder trunk with a distinctive groove pattern, initially drew attention. Closer examination revealed that the grooves were the result of claw marks from a large carnivore, possibly a bear, rather than human shaping.

This distinction is crucial. It shows the care taken by the researchers to avoid overinterpretation. It also paints a vivid picture of the site itself. Humans were not alone at this lakeshore. Large carnivores moved through the same space, leaving their own marks behind.

Professor Harvati notes that the presence of carnivore marks near the butchered elephant remains points to fierce competition between humans and large predators. This was a shared landscape, contested and dangerous, where access to resources could mean survival.

Pushing the Timeline of Wooden Technology

Before this discovery, the oldest known wooden tools came from places such as the United Kingdom, Zambia, Germany, and China, including weapons, digging sticks, and tool handles. All of them, however, are younger than the finds from Marathousa 1.

There is only one older piece of evidence for human use of wood, from Kalambo Falls in Zambia, dated to around 476,000 years ago. Yet that wood served as structural material, not as a hand-held tool. The difference matters. Using wood as part of a structure reflects one kind of planning. Shaping it to hold and use reflects another, more intimate relationship between hand, material, and purpose.

With the Marathousa 1 tools, researchers can now say with confidence that humans were crafting and using wooden hand-held tools much earlier than previously documented.

Why These Quiet Objects Matter So Much

At first glance, two small pieces of ancient wood may seem insignificant. They are not dramatic weapons or monumental structures. Yet their importance is profound. They remind us that much of early human life was built from materials that rarely survive, and that our picture of the past has long been incomplete.

These tools show that humans 430,000 years ago were not limited to stone and bone. They understood the properties of different trees. They selected alder, willow, or poplar for specific reasons. They shaped wood with intention and used it repeatedly, leaving behind traces of wear that still speak across time.

The discovery also highlights how exceptional sites like Marathousa 1 can transform our understanding. Preservation here was good enough to capture moments of daily life that usually disappear forever. It reveals humans competing with carnivores, butchering massive animals, and quietly working wood at the water’s edge.

Most importantly, this research reshapes how we think about the roots of human creativity. The hands that shaped these tools were already experimenting, adapting, and solving problems with materials beyond stone. In the grain of ancient wood, we see not just tools, but the early outlines of the technological mind that would one day reshape the world.

Study Details

Milks, Annemieke et al, Evidence for the earliest hominin use of wooden handheld tools found at Marathousa 1 (Greece), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2026). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2515479123