The ocean covers most of our planet, yet it remains more mysterious than the Moon or Mars. Satellites have mapped distant galaxies in exquisite detail, while vast regions of Earth’s own seafloor remain unseen by human eyes. Nowhere is this contrast more striking than in the oceanic trenches—long, narrow, crushingly deep scars in the planet’s crust that plunge kilometers below the surrounding seabed. These trenches are not merely deep places. They are environments so extreme that they challenge our understanding of life, geology, and even what it means for a world to be habitable.

To descend into an oceanic trench is to leave behind nearly every familiar reference point. Light vanishes within the first few hundred meters. Pressure rises relentlessly, crushing with the weight of entire mountain ranges. Temperatures hover just above freezing. And yet, life persists. Strange, resilient, and often beautiful, trench ecosystems thrive in conditions that would be instantly lethal to most organisms at the surface.

When we imagine the future—1,000 years from now—it is tempting to look to the stars. But the trenches beneath our oceans may be just as alien, just as transformative, and just as important to humanity’s future. They may become laboratories for understanding life’s limits, repositories of geological memory, and even testing grounds for new forms of exploration and adaptation. To understand what the trenches might become, we must first understand what they are, how they formed, and why they matter.

The Birth of Oceanic Trenches in a Living Planet

Oceanic trenches are born from the restless motion of Earth’s tectonic plates. The planet’s outer shell is not a single unbroken surface but a mosaic of massive plates that drift slowly over the hotter, more fluid mantle beneath. Where these plates collide, one may be forced downward into the mantle in a process known as subduction. The place where this descent begins is marked by a trench.

These trenches are the deepest features on Earth’s surface. Some stretch for thousands of kilometers, tracing the boundaries of colliding plates like wounds that never heal. The deepest known point in the ocean lies within such a trench, where the seafloor plunges to depths that defy ordinary comprehension. At these depths, pressure exceeds a thousand times that at sea level, enough to collapse most materials not specifically designed to withstand it.

But trenches are not static scars. They are dynamic, evolving structures, shaped by earthquakes, volcanic activity, and the slow recycling of Earth’s crust. Sediments slide down their steep walls, carrying organic material from the surface into the depths. Chemical reactions occur as seawater interacts with descending rock, altering both the ocean and the planet’s interior. Trenches are places where the surface world and the deep Earth meet, exchange matter, and reshape each other over geological time.

A Realm Without Sunlight

Sunlight is the foundation of most life on Earth, driving photosynthesis and shaping ecosystems from forests to coral reefs. In oceanic trenches, sunlight is entirely absent. Even the faint glow that penetrates the upper deep ocean disappears long before the trench floor is reached. These depths exist in perpetual night, untouched by the daily rhythms of sunrise and sunset.

In the absence of light, life has followed a different path. Instead of relying on photosynthesis, trench ecosystems are fueled by chemical energy. Organic material produced at the surface sinks slowly downward, a steady rain of particles known as marine snow. This detritus becomes a vital food source, sustaining communities of organisms adapted to scarcity and darkness.

In some trench regions, chemical processes provide additional energy. Microbes use compounds such as methane or hydrogen sulfide to fuel chemosynthesis, a process that converts chemical energy into organic matter. This strategy, entirely independent of sunlight, allows life to flourish even in the deepest and darkest corners of the ocean.

The result is an ecosystem that feels almost extraterrestrial. Creatures glow with bioluminescent light, producing flashes and glimmers in the darkness. Bodies are often soft and gelatinous, designed to withstand pressure rather than resist it. Eyes, if present at all, are adapted to detect the faintest hints of light, or they may be absent entirely.

Life Under Crushing Pressure

Pressure is the defining feature of oceanic trenches. For every ten meters of depth, pressure increases by roughly one atmosphere. In the deepest trenches, pressure reaches levels that would crush a human body instantly. Yet life not only survives but thrives under these conditions.

Trench organisms are masterpieces of adaptation. Their cellular membranes contain special lipids that remain flexible under extreme pressure. Their proteins are structured to function without collapsing or denaturing. Enzymes that would fail at the surface operate efficiently in the cold, high-pressure environment of the deep.

These adaptations are not just biological curiosities. They offer clues about life’s fundamental resilience. By studying trench organisms, scientists gain insight into how life might exist in similarly extreme environments elsewhere, such as beneath the icy crusts of distant moons or in the subsurface oceans of other worlds.

In a sense, oceanic trenches are Earth’s natural experiments in extremity. They show that life is not confined to narrow comfort zones but can expand into realms once thought uninhabitable. This realization reshapes our understanding of biology and broadens our vision of where life might be found.

The Silent Influence of Trenches on the Global Ocean

Though remote and hidden, oceanic trenches play a subtle but significant role in the global ocean system. They act as sinks for organic carbon, drawing material from the surface and locking it away in deep sediments. Over long timescales, this process influences Earth’s carbon cycle, affecting climate and atmospheric composition.

Trenches also interact with ocean circulation. Dense, cold water flows along the seafloor and can become trapped or redirected by trench topography. These movements affect how heat, nutrients, and dissolved gases are distributed throughout the deep ocean.

Earthquakes generated along subduction zones can trigger underwater landslides, sending waves of sediment cascading into trenches. These events reshape the seafloor and inject pulses of nutrients into deep ecosystems. In this way, trenches are not isolated abysses but active participants in the planet’s interconnected systems.

Understanding these processes is crucial for building accurate models of Earth’s climate and geochemical cycles. As human activity increasingly alters the surface environment, the role of deep-sea processes becomes ever more important in determining the planet’s long-term stability.

Human Encounters with the Deepest Depths

For most of human history, oceanic trenches were beyond imagination, let alone exploration. Even today, reaching their depths requires extraordinary technology. Specialized submersibles, built from advanced materials and designed to withstand immense pressure, have carried a handful of explorers to the trench floors.

These missions reveal landscapes that are both stark and hauntingly beautiful. The seafloor may appear smooth and sediment-covered, interrupted by steep walls and occasional outcrops of rock. Life appears sparse at first glance, but closer inspection reveals a surprising diversity of organisms, each adapted to a world without light or warmth.

Human presence in these environments is fleeting. Submersibles can remain at depth only for limited periods, and the logistical challenges of deep-sea exploration are immense. Yet each descent expands our understanding and deepens our sense of wonder. The trenches remind us that Earth still holds vast unknowns, waiting patiently beneath the waves.

The Trenches as Archives of Earth’s History

Sediments accumulating in oceanic trenches act as natural archives, preserving a record of Earth’s past. Layer by layer, particles settle and remain undisturbed for thousands or even millions of years. These sediments contain clues about ancient climates, volcanic eruptions, and biological activity at the surface.

By extracting sediment cores from trench regions, scientists can reconstruct changes in ocean chemistry, temperature, and productivity over time. These records provide context for understanding current environmental changes and predicting future trends.

In this way, trenches function as memory vaults of the planet. They hold evidence of long-gone ecosystems, past climate shifts, and the slow evolution of Earth’s surface. Protecting and studying these archives is essential for gaining a full picture of our planet’s history.

Pollution Reaches the Deepest Places

One of the most sobering discoveries of recent decades is that even the deepest oceanic trenches are not untouched by human influence. Microplastics, industrial chemicals, and other pollutants have been found in trench sediments and organisms. Carried by ocean currents and sinking particles, human-made debris reaches depths once thought isolated from surface activity.

This realization underscores the interconnectedness of Earth’s systems. No place on the planet is truly separate from human actions. The trenches, once symbols of pristine wilderness, now reflect the global reach of pollution.

Understanding how contaminants accumulate and persist in deep-sea environments is a growing area of research. The long-term effects on trench ecosystems are still poorly understood, but the presence of pollution raises urgent questions about responsibility and stewardship.

Imagining the Trenches 1,000 Years from Now

Looking ahead a thousand years invites both caution and imagination. Human technology is advancing rapidly, and our relationship with the ocean is changing. The trenches of the future may be very different from those we know today.

In one possible future, oceanic trenches become sites of sustained exploration. Autonomous vehicles, guided by artificial intelligence, may roam the depths continuously, mapping terrain, monitoring ecosystems, and collecting data. Human presence may remain rare, but our understanding could expand dramatically.

These technologies could transform trenches into living laboratories. Long-term observatories might track seismic activity, chemical fluxes, and biological changes in real time. Such systems would deepen our understanding of Earth’s inner workings and improve our ability to predict natural hazards like earthquakes and tsunamis.

At the same time, the trenches may play a role in humanity’s search for new resources. Advances in engineering could make it feasible to access minerals or other materials from deep-sea environments. Whether this future unfolds responsibly or recklessly will depend on choices made long before the thousand-year mark is reached.

Life’s Future in the Deep

The biological future of oceanic trenches is uncertain. Climate change is altering ocean temperatures, circulation patterns, and chemistry. These changes will inevitably affect the deep sea, though the extent and pace remain unclear.

Some trench ecosystems may prove resilient, buffered by their isolation and slow rates of change. Others may be vulnerable to shifts in food supply or chemical conditions. Because trench organisms often grow slowly and reproduce infrequently, recovery from disturbance could take centuries.

In a thousand years, new forms of life may evolve, shaped by changing conditions and perhaps influenced by human activity. Alternatively, some unique lineages may disappear, lost before they are fully understood. The trenches remind us that biodiversity is not only a surface phenomenon but extends into the deepest reaches of the planet.

The Trenches and the Search for Alien Life

Oceanic trenches have become powerful analogs for extraterrestrial environments. The icy moons of the outer solar system are believed to harbor subsurface oceans beneath thick shells of ice. These oceans are dark, cold, and potentially high-pressure, conditions reminiscent of Earth’s deep trenches.

By studying how life survives and adapts in trenches, scientists gain insight into how life might exist elsewhere. Chemosynthetic ecosystems, pressure-resistant biology, and energy-limited survival strategies offer models for life beyond Earth.

In this sense, trenches are not just features of our planet but windows into the broader question of life in the universe. They teach us that habitability is not limited to sunlit surfaces but can extend into hidden, extreme realms.

Ethical Questions at the Edge of the Abyss

As our ability to explore and exploit the deep ocean grows, ethical questions loom large. Who has the right to access and use trench environments? How do we balance scientific discovery, economic interests, and conservation?

The trenches challenge traditional ideas of ownership and responsibility. They lie beyond national borders, in international waters that belong to no single nation. Decisions about their future will require global cooperation and foresight.

In a thousand years, humanity may look back on the early twenty-first century as a turning point, when the fate of the deep ocean was decided. Whether that legacy is one of care or neglect remains an open question.

Emotional Power of the Deepest Places

There is something profoundly moving about oceanic trenches. They embody both the fragility and the resilience of life, the vastness of the unknown, and the limits of human experience. To contemplate these depths is to confront our own smallness, but also our capacity for curiosity and understanding.

The trenches evoke a sense of the alien not because they are separate from Earth, but because they reveal aspects of our planet that lie beyond everyday perception. They remind us that reality is richer and stranger than it appears from the surface.

In this emotional resonance lies much of their power. The trenches are not just scientific subjects but sources of wonder, capable of inspiring art, philosophy, and a renewed sense of connection to the planet.

A Thousand Years of Possibility

In a thousand years, oceanic trenches may still be largely unexplored, or they may be among the best-studied environments on Earth. They may serve as refuges for unique life, as archives of planetary history, or as cautionary tales of environmental neglect.

What seems certain is that they will continue to challenge and inspire us. As long as humanity seeks to understand its world, the trenches will stand as reminders that even on our own planet, there are alien worlds waiting to be known.

At the bottom of the sea, in darkness and silence, the Earth reveals some of its deepest truths. The future of those truths, and of the trenches themselves, depends on how we choose to listen.

Study Details

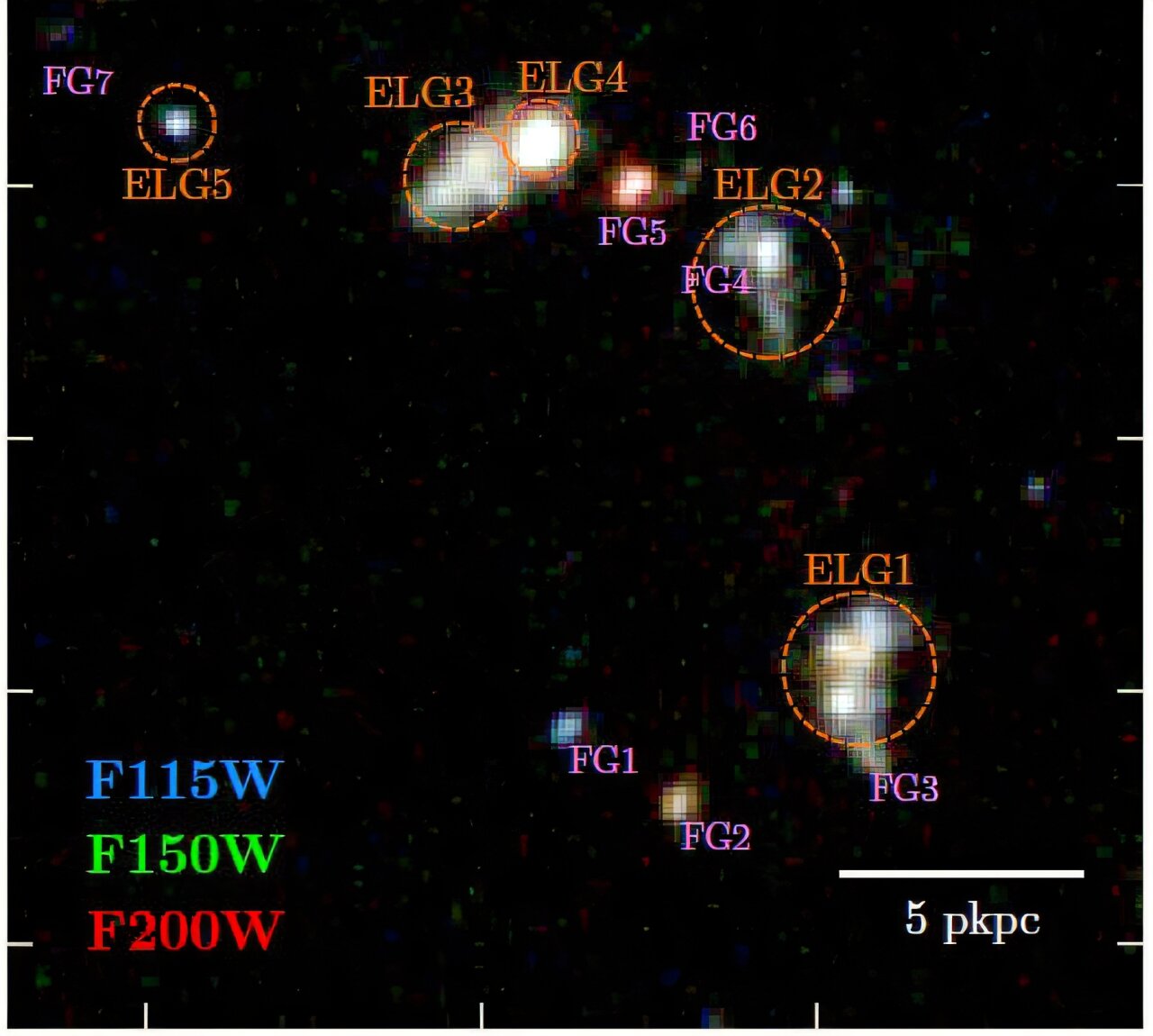

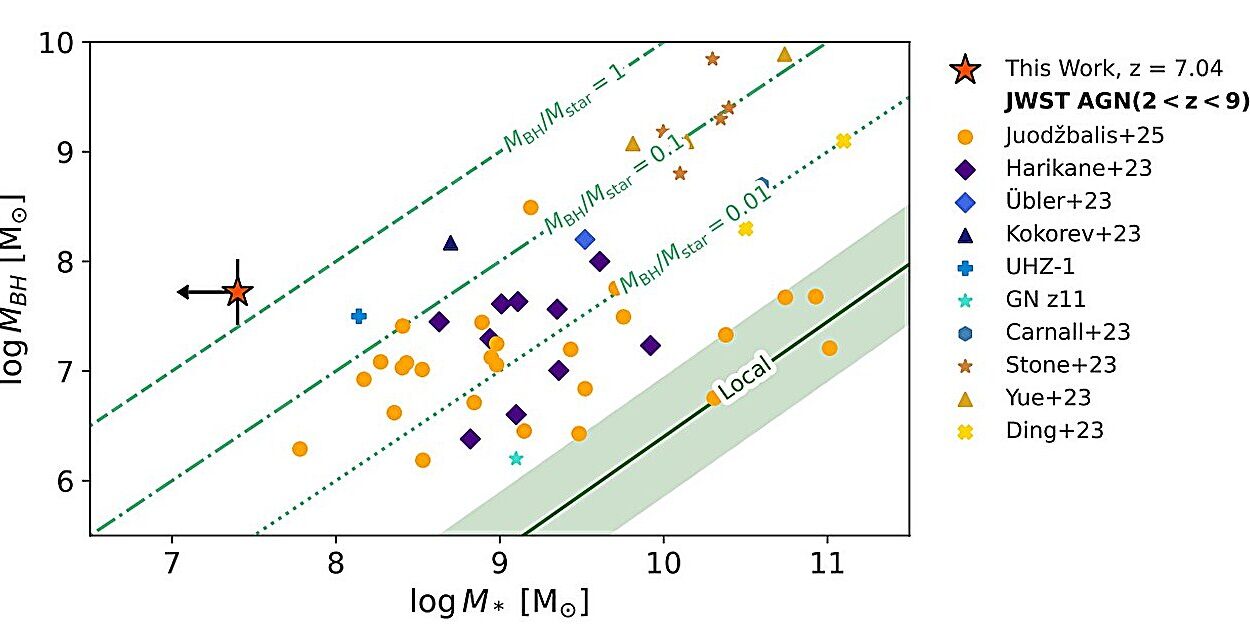

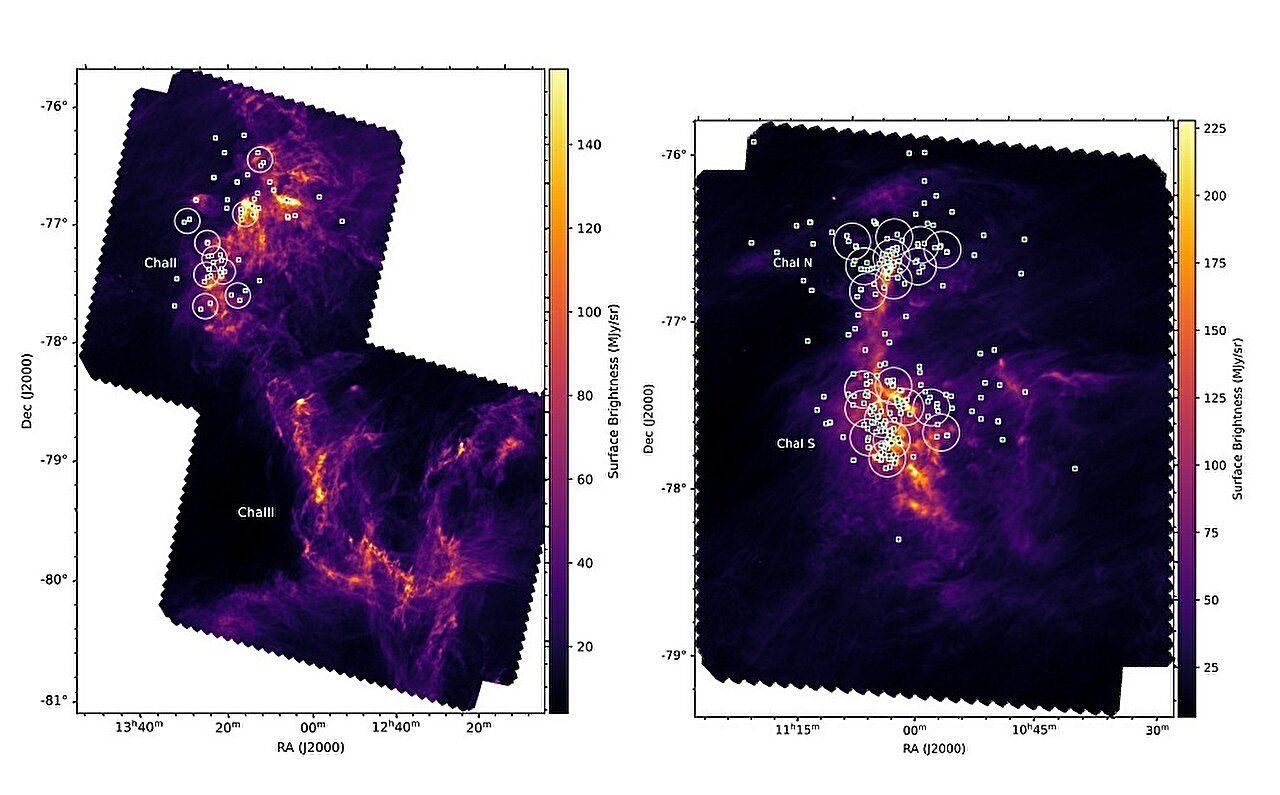

Weida Hu et al, Extended enriched gas in a multi-galaxy merger at redshift 6.7, Nature Astronomy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02636-1