For centuries, dementia has been one of medicine’s most painful mysteries. It robs people not only of memory but of identity, unraveling the threads of personality and leaving families watching helplessly as loved ones fade. Among the different forms of dementia, Lewy body dementia stands out as particularly devastating, blending memory loss with hallucinations, sleep disturbances, and Parkinson’s-like symptoms. Now, in groundbreaking research, a team at Johns Hopkins Medicine has uncovered a potential molecular connection between air pollution and this cruel disease, shining a spotlight on an invisible but powerful threat in our daily environment.

The Ghost in the Brain: What Are Lewy Bodies?

At the heart of Lewy body diseases lies a microscopic saboteur: a protein called alpha-synuclein. In healthy brains, this protein plays a role in communication between neurons. But when it misfolds and clumps together, it forms toxic clusters known as Lewy bodies. These sticky protein tangles disrupt brain function, kill neurons, and trigger the cognitive decline characteristic of both Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia.

Think of the brain as a symphony, where each neuron is an instrument playing in harmony. Lewy bodies are like patches of static that spread through the orchestra, throwing the music into disarray. The question scientists have long struggled to answer is: why do these toxic protein clumps form in the first place?

A Polluted Connection

The new study, published in Science, suggests that the air we breathe may be part of the answer. Fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5, is composed of microscopic particles released from cars, factories, wildfires, and even residential stoves. Invisible to the naked eye, these tiny particles slip deep into the lungs and, as evidence increasingly shows, can travel from the bloodstream into the brain.

Over the last decade, research has linked PM2.5 exposure to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s. But the Johns Hopkins team, led by Dr. Xiaobo Mao, wanted to go deeper. Could air pollution specifically spark the formation of Lewy bodies? And if so, could this explain why people exposed to dirty air seem to develop dementia at higher rates?

From Big Data to the Lab

The investigation began with an ambitious analysis of U.S. hospital records. The researchers combed through data from more than 56 million patients admitted between 2000 and 2014. By pairing ZIP code information with air quality records, they estimated long-term exposure to PM2.5 for each patient. The results were striking: every significant increase in PM2.5 concentration correlated with a 17% higher risk of Parkinson’s disease dementia and a 12% higher risk of dementia with Lewy bodies.

This was more than a statistical blip. It was a strong signal that polluted air was linked not just to dementia in general but specifically to disorders driven by Lewy bodies. With this evidence in hand, the team turned to the laboratory to uncover the biology behind the numbers.

Mice, Memory, and Molecular Clues

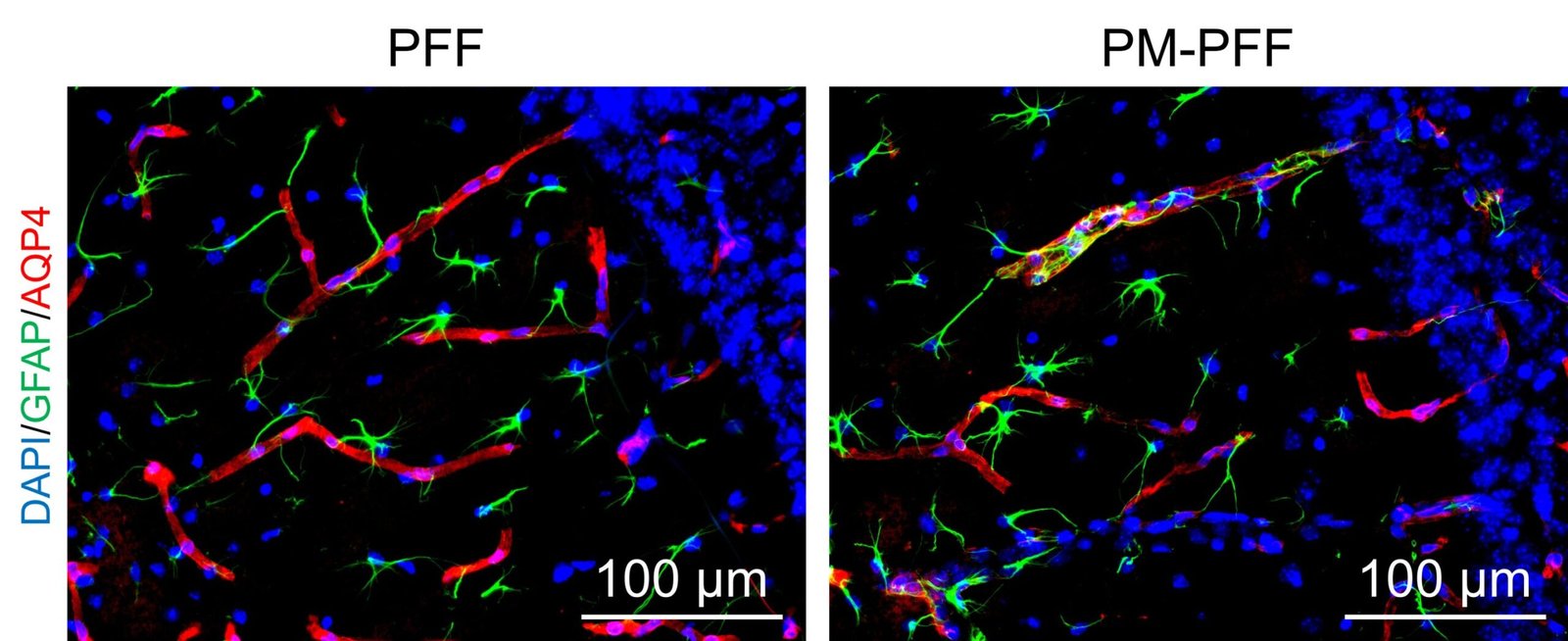

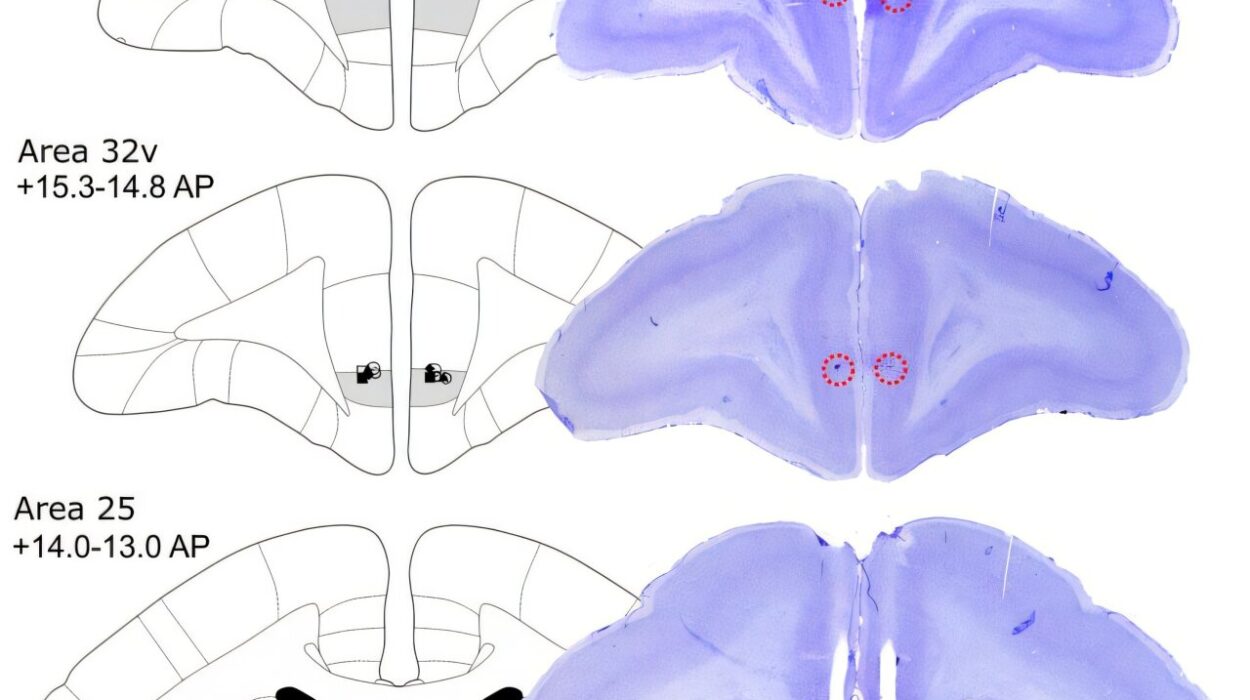

To probe the connection, Mao’s group exposed mice to PM2.5 over the course of months—simulating the kind of chronic pollution people encounter in real life. The results were unsettling. In normal mice, prolonged exposure triggered brain atrophy, cell death, and cognitive decline eerily similar to Lewy body dementia in humans. Under the microscope, their brains revealed clusters of misfolded alpha-synuclein proteins, the very hallmark of the disease.

In contrast, mice genetically engineered to lack alpha-synuclein did not develop these changes. Their brains remained largely intact, suggesting that air pollution’s destructive effects hinged on this single vulnerable protein.

To make matters more compelling, when the researchers exposed mice carrying a human gene mutation known to cause early-onset Parkinson’s disease, the damage was even more severe. Within five months, their brains were riddled with alpha-synuclein clumps, accompanied by cognitive decline.

What the researchers found most fascinating was that the protein clumps formed under pollution exposure were not identical to those that appear during natural aging. These new clusters were a distinct “strain” of Lewy bodies—novel toxic structures that may represent a unique fingerprint of air pollution’s impact on the brain.

A Universal Threat

Pollution, of course, is not confined to one country. To test whether geography matters, the team exposed mice to PM2.5 samples collected from the United States, Europe, and China. The results were grimly consistent: no matter where the particles came from, the mice developed similar brain damage and Lewy body formation.

This finding suggests a chilling truth: the risk posed by air pollution is not tied to a specific region’s industrial mix but may be a universal property of fine particulate matter itself.

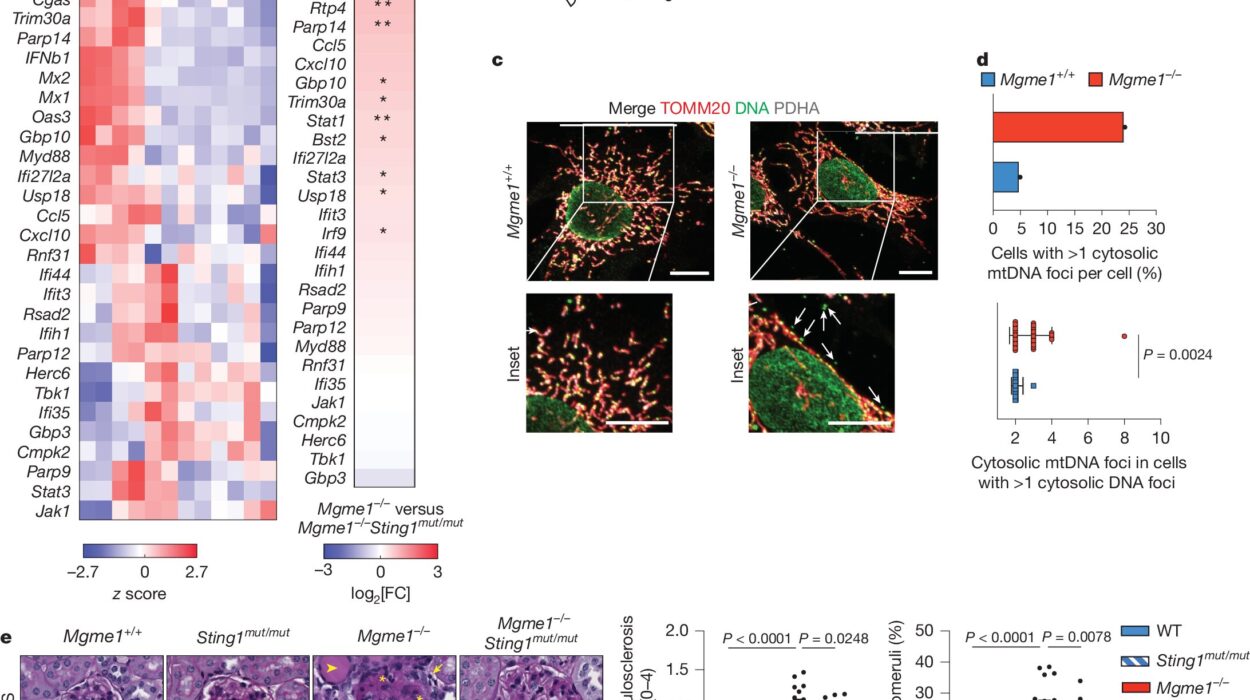

The Human Parallel

Perhaps the most compelling evidence came from comparing gene activity in the brains of pollution-exposed mice with postmortem brains from patients who had Lewy body dementia. The overlap was striking. The same disease-related gene expression changes seen in humans appeared in the mice, strongly supporting the idea that PM2.5 does not just accelerate aging but may directly mimic and drive the disease process.

As Dr. Shizhong Han, a collaborator on the study, explained, “This suggests that pollution may not only trigger the build-up of toxic proteins but also reprogram the brain at a genetic level.” In other words, air pollution could be acting as both a spark and a fuel for neurodegeneration.

Beyond Genes: A Matter of Choice

Genetics undoubtedly play a role in who develops neurodegenerative diseases, but one of the most hopeful aspects of this study is the idea of control. Unlike our genes, environmental exposures can be changed. If pollution contributes to Lewy body dementia, then reducing exposure could lower risk.

Dr. Mao and his colleagues emphasize the importance of identifying the most harmful components of PM2.5. Not all particles are equal—some may be far more dangerous to the brain than others. Pinpointing these could guide policymakers and public health officials in designing smarter regulations to protect vulnerable populations.

A Call for Awareness and Action

The implications of this research ripple far beyond the laboratory. For city planners, it highlights the hidden neurological cost of unchecked pollution. For doctors, it raises the possibility of using environmental history as a risk factor in dementia screening. For families, it underscores the importance of clean air not just for physical health but for preserving memory, personality, and dignity.

But perhaps most importantly, it reframes how we think about dementia itself. Lewy body dementia is not only a product of aging or genetics. It may also be, in part, a disease of our modern world, shaped by the invisible particles we inhale every day.

The Fragile Balance of Brain and Environment

The brain, for all its complexity, is astonishingly vulnerable. A few misfolded proteins can derail decades of memory. A tiny change in gene expression can tilt the balance toward degeneration. This new research is a sobering reminder of how deeply the environment seeps into our biology, blurring the line between the world outside us and the world within.

And yet, there is hope. By uncovering this molecular link, scientists have opened the door to new strategies for prevention and treatment. If we can identify and block the specific “strain” of Lewy bodies triggered by pollution, future therapies may not only slow dementia but stop it before it begins.

Looking Ahead

The story of Lewy body dementia is far from over. But with each discovery, we move closer to understanding how and why this disease unfolds. The Johns Hopkins study is more than a scientific achievement—it is a call to recognize the cost of pollution not only on lungs and hearts but on the most human part of us all: the mind.

In the end, the findings remind us of a profound truth. The air we breathe does not simply sustain life; it shapes it. Clean air is not just a matter of comfort or convenience—it may be one of the most powerful tools we have to protect memory, preserve identity, and safeguard the essence of who we are.

More information: Xiaodi Zhang et al, Lewy body dementia promotion by air pollutants, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu4132. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adu4132