Inhale. Exhale. Every breath we take is a quiet testament to life. Yet for millions of people across the world, that act of breathing—a process so automatic it often goes unnoticed—becomes a daily struggle. Lung cancer does not arrive with a loud announcement. It creeps in silently, often undetected, until it’s already deep within the lungs, making its presence known through persistent coughs, fatigue, or fleeting chest pain.

It is not just a disease of the lungs; it is a thief of voice, energy, clarity, and time. For many, it arrives burdened with guilt or stigma—especially for those who smoked. But lung cancer is not just a smoker’s disease, and its reach goes far beyond cigarette ash. It is complex, devastating, and yet—more than ever before—potentially survivable, thanks to rapid advances in early detection and treatment. To understand lung cancer is to illuminate the silent spaces in our bodies where cells rebel, and where hope must outpace fear.

The Cellular Rebellion: What Lung Cancer Really Is

At its most basic level, lung cancer is the result of cells in the lung growing out of control. Like all cancers, it begins with a single cell that, due to damage or mutation, breaks free from the normal rules of growth and repair. Instead of dying when it should, it keeps dividing. It no longer communicates effectively with its neighbors. It ignores the body’s alarms. Eventually, it forms a mass—what we call a tumor.

But lung cancer is not just one disease. It is a category that contains many distinct types and subtypes, each with its own biology, behavior, and prognosis. The lungs, with their sprawling branches of bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli, offer many places for cancer to take hold. Some tumors grow quietly in the periphery; others clog the central airways. Some spread like wildfire; others remain slow and localized.

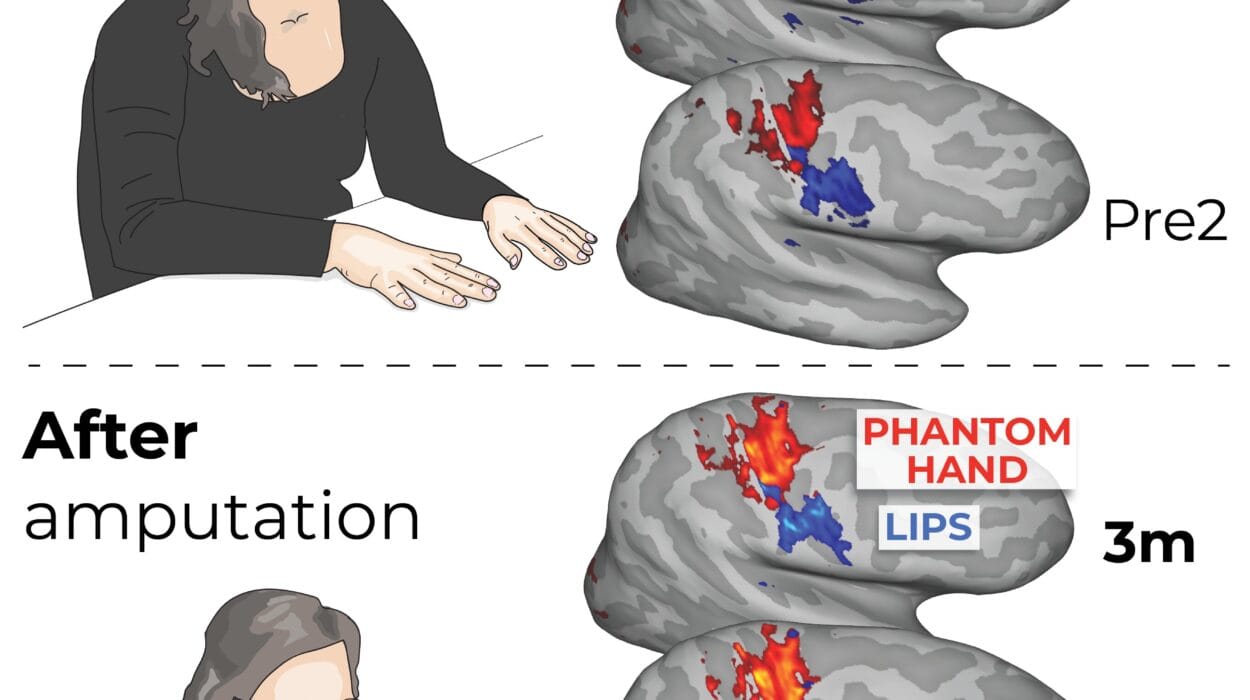

What makes lung cancer especially insidious is its tendency to remain silent in its early stages. The lungs lack pain receptors, so tumors can grow for months or even years without causing noticeable symptoms. By the time a cough or weight loss prompts a medical visit, the disease may have already spread—either within the lungs or beyond them.

Triggers in the Air: What Causes Lung Cancer?

The most well-known cause of lung cancer is tobacco smoke. Decades of research have confirmed this beyond doubt: cigarettes are responsible for approximately 85% of lung cancer cases. Tobacco smoke contains over 7,000 chemicals, including at least 70 that are known carcinogens—such as benzene, formaldehyde, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Each inhale delivers a toxic cocktail to the delicate tissues of the lungs, damaging DNA and overwhelming the cells’ repair mechanisms.

But lung cancer doesn’t end with smoking. A significant portion—up to 15% of cases—occur in people who have never smoked. In these patients, the causes are often more elusive but no less real. Radon gas, a naturally occurring radioactive element that seeps from soil into homes, is the second leading cause of lung cancer. It is invisible and odorless, making it especially dangerous.

Other culprits include occupational exposures to asbestos, arsenic, diesel exhaust, and industrial pollutants. Air pollution itself, particularly fine particulate matter from vehicle emissions and coal burning, has been classified as a carcinogen by the World Health Organization. And then there are the biological wild cards—genetic mutations inherited from parents or acquired randomly, for reasons still unknown.

In women and young non-smokers, certain gene mutations—especially in the EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 genes—are increasingly recognized as triggers. These mutations often drive the growth of specific subtypes of lung cancer, particularly adenocarcinoma, and are now targets for precision therapies.

Unfolding in Shadows: How Lung Cancer Progresses

Lung cancer’s story unfolds through stages—a progression that reflects how far the disease has spread and what it’s doing to the body. Medical professionals use the TNM system: T for the size and location of the primary tumor, N for the involvement of nearby lymph nodes, and M for metastasis, or the spread to distant organs. These metrics are combined to create an overall stage from 0 to IV.

Stage 0, sometimes called “carcinoma in situ,” is the earliest. The cancer is confined to a small area and hasn’t invaded deeper tissues. At this point, it may be curable with surgery alone. But Stage I and II, though still localized, may require more aggressive treatment. Stage III involves spread to regional lymph nodes, often in the center of the chest. And Stage IV—metastatic lung cancer—is the most advanced, where cancer has traveled to distant organs such as the brain, liver, bones, or adrenal glands.

The experience of living through these stages is not just medical—it is emotional, existential. Early-stage patients grapple with the fear of recurrence. Those with advanced disease face choices about quality of life, treatment burdens, and hope. The medical staging offers structure, but the human experience resists categorization. It is filled with unpredictability, courage, and deeply personal decisions.

The Faces of Lung Cancer: Types and Subtypes

Lung cancer is generally divided into two main categories based on how the cells look under a microscope.

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) accounts for about 85% of all cases. It includes several subtypes:

- Adenocarcinoma is the most common, particularly in non-smokers and women. It typically arises in the outer regions of the lungs.

- Squamous cell carcinoma is more strongly associated with smoking and tends to develop in the central airways.

- Large cell carcinoma is rarer and more aggressive, often growing quickly and spreading early.

Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC), which makes up the remaining 15%, is a fast-growing, aggressive form often found in smokers. It tends to spread quickly and is usually diagnosed at a later stage. While initially very responsive to chemotherapy and radiation, SCLC often recurs, sometimes within months.

These distinctions are not academic—they guide treatment. A patient with an EGFR-mutant adenocarcinoma may benefit from targeted pills rather than standard chemotherapy. Someone with limited-stage SCLC may receive a combination of chemotherapy and radiation with curative intent. The challenge lies in making the right diagnosis early, before the disease outpaces intervention.

Detection in the Fog: The Challenge of Diagnosis

Because symptoms of lung cancer often mimic less serious conditions like bronchitis or pneumonia, diagnosis is frequently delayed. Persistent cough, coughing up blood, chest pain, hoarseness, shortness of breath—these may not appear until the cancer has progressed significantly.

Imaging tests are typically the first step. A chest X-ray may reveal a suspicious mass, but it lacks sensitivity. CT scans provide a more detailed look, helping identify the size, shape, and location of tumors. PET scans reveal metabolic activity, showing how “hot” or active the cancer is, while MRIs are particularly useful for detecting brain metastases.

Confirming lung cancer requires a biopsy—removing a small sample of tissue for microscopic analysis. This may be done via bronchoscopy (threading a camera into the lungs), CT-guided needle biopsy, or even surgery. Once the tissue is obtained, it’s analyzed for cell type, molecular markers, and mutations. This “molecular fingerprinting” is crucial for personalized medicine, which has transformed treatment in recent years.

Fighting Fire with Science: Treatment Options

Lung cancer treatment is no longer a blunt instrument. It is increasingly a precision strike—tailored, targeted, and, at times, remarkably effective. The choice of treatment depends on many factors: the type and stage of cancer, molecular profile, overall health, and patient preferences.

In early stages, surgery is often the first option—removing the tumor along with part of the lung (lobectomy or pneumonectomy). Sometimes it’s followed by chemotherapy or radiation to kill residual cells. In patients who cannot tolerate surgery, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) offers a highly focused alternative, delivering lethal doses of radiation to tumors while sparing nearby tissues.

For advanced cases, chemotherapy has long been the backbone of treatment. It attacks rapidly dividing cells, including cancer—but also harms healthy tissues, leading to hair loss, nausea, fatigue, and immune suppression.

Targeted therapy, by contrast, goes after specific mutations driving the cancer. Drugs like osimertinib (for EGFR), crizotinib (for ALK), and entrectinib (for ROS1) can shrink tumors dramatically, with fewer side effects. However, resistance can develop over time, requiring changes in therapy.

Immunotherapy has ushered in a new era. By unleashing the body’s own immune system, drugs like pembrolizumab and nivolumab have provided long-term remissions in some patients with advanced disease. These checkpoint inhibitors block the “don’t eat me” signals cancer cells send to T-cells, allowing the immune army to attack.

Radiation continues to play a vital role—especially in cases where surgery isn’t possible or when treating specific symptoms like brain metastases. And for some, clinical trials offer access to the newest treatments before they’re widely available.

Beyond the Body: The Emotional Terrain

A diagnosis of lung cancer is never just physical. It penetrates the psyche, the relationships, the future plans. Patients often experience fear, guilt, anger, and grief—not only about their health, but about the disruption of identity and routine. Many wrestle with stigma, especially if they smoked. Others feel isolated, as lung cancer has historically received less public sympathy and funding than other cancers.

Support groups, counseling, and palliative care are vital parts of the treatment journey. These are not optional extras—they are essential to healing, even when cure is not possible. Palliative care, in particular, focuses on relieving symptoms, improving quality of life, and supporting families, from diagnosis onward—not just at the end.

Hope in the Horizon: Survival and Innovation

Though lung cancer remains one of the deadliest cancers worldwide, survival rates are improving—especially for those diagnosed early. The five-year survival rate for localized non-small cell lung cancer can be as high as 63%, compared to just 7% for distant-stage disease. For small cell lung cancer, survival is still challenging, but new regimens are emerging.

Low-dose CT screening has begun to shift the tide. For high-risk individuals—such as heavy smokers aged 50 and above—regular screening can catch lung cancer at earlier, more treatable stages. Public awareness is slowly growing, and stigma is being challenged by survivors and advocates who declare, rightly, that no one deserves cancer.

The pipeline of innovation is full: liquid biopsies that detect cancer from a blood sample, new immunotherapy combinations, vaccines that train the immune system to attack tumors, and AI tools that analyze scans for early changes invisible to the human eye.

Breathing Forward: A Story of Resilience

Lung cancer is not just a statistic or a scan. It is a father watching his daughter graduate despite a terminal diagnosis. It is a young woman defying the odds through targeted therapy. It is a researcher staring down a microscope, dreaming of a world where cancer is a memory, not a sentence.

It is, at its core, a story of breath—the fight to keep breathing, the courage to keep living, the science that makes survival possible.