Deep within the quest for a greener planet lies a stubborn paradox: the very chemicals we need to store renewable energy are often the ones most likely to destroy the machines that hold them. For years, scientists have looked toward the zinc–bromine flow battery as a savior for grid-scale storage. These systems are unique because they store energy in liquid electrolytes kept in external tanks, a design that makes them incredibly scalable. But these batteries have long been haunted by a chemical duality—the element bromine is simultaneously the engine of their power and the source of their decay.

The corrosive heart of the battery

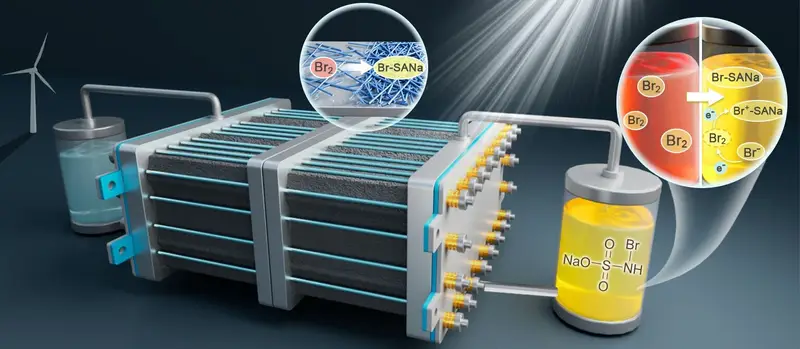

To understand the challenge, one must look at how these liquid power plants breathe. During the charging process, zinc ions plate onto a negative electrode as solid metal, while bromide ions are oxidized into bromine at the positive electrode. When it is time to discharge that energy back into the grid, the reactions reverse. This cycle is what allows the battery to act as a massive reservoir for wind or solar power. However, bromine is a notoriously difficult guest.

In its natural state during operation, bromine is highly volatile and toxic. It is so aggressive that it literally eats the battery from the inside out, corroding the electrodes, the pipes, and even the storage tanks. This chemical aggression means that conventional systems often see a sharp drop in performance after only 30 cycles. Beyond the mechanical damage, the safety risks are significant. Small leaks can release vapors that pollute the air, irritate human tissue, and even interfere with the nervous system. For a long time, the dream of a long-lasting bromine battery seemed trapped behind a wall of rust and risk.

A molecular scavenger joins the fray

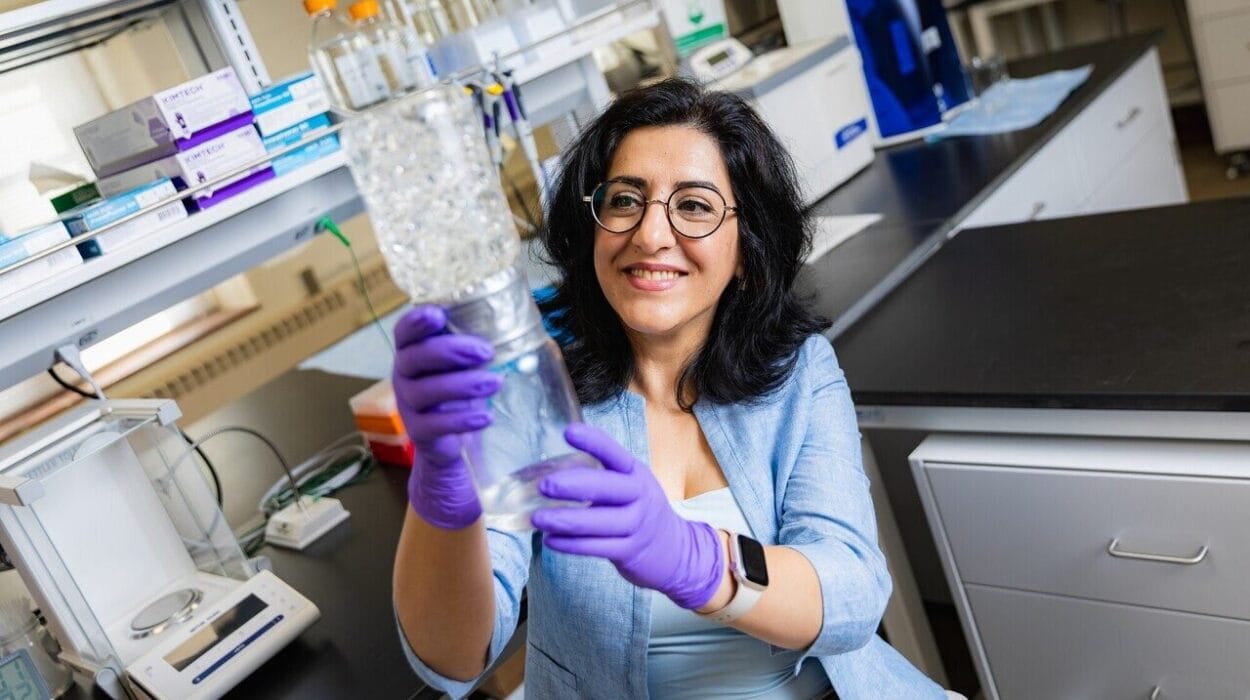

Researchers refused to accept that bromine had to be a destructive force. They began searching for a chemical antidote, a way to tame the element without stripping it of its energy-storing potential. Their breakthrough came in the form of a simple molecular scavenger called sodium sulfamate, or SANa. By adding this scavenger directly into the electrolyte solution, the team discovered they could fundamentally alter how bromine behaves when the battery is under load.

The SANa acts as a sophisticated chemical trap. When the battery charges and bromine (represented chemically as Br₂) is produced, the scavenger initiates a specific type of redox process known as a disproportionation reaction. In this elegant chemical dance, the bromine gas is split and bound to the scavenger, converting the hazardous substance into a much milder product called N-bromo sodium sulfamate. This transformation effectively “cages” the tiger. By binding the bromine into this new form, the researchers managed to slash the concentration of free-floating, corrosive bromine down to a manageable level of approximately 7 millimoles per liter.

Doubling the power and the lifespan

The introduction of SANa did more than just stop the rot; it unlocked a hidden level of efficiency. The researchers observed a two-electron transfer phenomenon triggered by the scavenger’s interaction with the bromine. This meant the battery wasn’t just safer—it was significantly more powerful. While conventional versions of these batteries typically reach an energy density of about 90 Wh/l, the new design fortified with the scavenger surged to 152 Wh/l.

This leap in density was matched by a staggering increase in endurance. To prove the discovery worked in the real world, the team built a 5 kW stack featuring 30 individual battery cells connected in series. The results were transformative. While old designs withered after a few dozen uses, this redesigned flow battery powered through over 700 stable cycles. This represents nearly 1,400 hours of continuous operation without any significant loss in performance. By trapping the bromine, the scientists had effectively stopped the clock on the battery’s aging process.

Stripping away the cost of complexity

The beauty of this discovery lies in its simplicity. Because the electrolyte itself is now “mild” and non-corrosive, the physical architecture of the battery can change. In the past, manufacturers had to use exotic, expensive corrosion-resistant membranes, specialized pumps, and heavy-duty storage tanks to survive the chemical onslaught. These requirements drove up the price of energy storage, making it difficult to compete with dirtier alternatives.

With the SANa scavenger doing the heavy lifting at the molecular level, these expensive safeguards become unnecessary. The battery can be built with standard, lower-cost materials because the liquid inside is no longer trying to dissolve its container. This shift lowers the barrier to entry for grid-scale applications, offering a pathway to store massive amounts of energy at a much lower price point. It turns a temperamental, high-maintenance technology into a durable workhorse for the modern electrical grid.

Why this chemical breakthrough matters

This research represents a pivotal shift in how we approach the transition to renewable energy. For the world to move away from fossil fuels, we need more than just solar panels and wind turbines; we need a way to keep the lights on when the sun sets and the wind stops. Zinc–bromine flow batteries have always been a promising candidate for this role because they are inherently scalable and made from low-cost materials. However, their short lifespan and toxic nature kept them on the sidelines.

By solving the bromine problem with a simple additive, these researchers have cleared the path for a new generation of high-energy-density storage. We now have a blueprint for batteries that are not only high-performing but also environmentally safer and more affordable. This work ensures that the infrastructure of our future power grid can be as clean and resilient as the energy it carries, providing a stable foundation for a world powered by the elements.

Study Details

Yue Xu et al, Grid-scale corrosion-free Zn/Br flow batteries enabled by a multi-electron transfer reaction, Nature Energy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41560-025-01907-5