Along the dry coast of what is now northern Chile, thousands of years ago, a small community lived between the ocean and the desert. They fished, crafted tools, raised children, and buried their dead. But unlike most ancient societies, the Chinchorro did not let death quietly take its course. Instead, they transformed it. They opened bodies, rebuilt them, painted them, and returned them to the world in altered form. Long before pyramids or embalming rituals elsewhere, the Chinchorro were creating artificial mummies.

A new study published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal suggests that this astonishing tradition may have begun not as ritual or display, but as an intimate human response to unbearable loss. According to Dr. Bernardo Arriaza, the Chinchorro’s earliest mummies may have been born from grief itself, shaped by parents trying to cope with the frequent deaths of their infants.

The idea reframes one of the world’s oldest mortuary traditions as something deeply emotional. The Chinchorro mummies, in this view, are not only archaeological remains. They are frozen expressions of sorrow, care, and love.

A People Who Lived With the Sea and the Dead

The Chinchorro were not static or primitive. They were a highly dynamic group of skilled fishers, artisans, and morticians who lived along the coast of the Atacama Desert. Between roughly 7000 and 3500 years before present, they developed and refined a unique practice of artificial mummification that set them apart from other ancient societies.

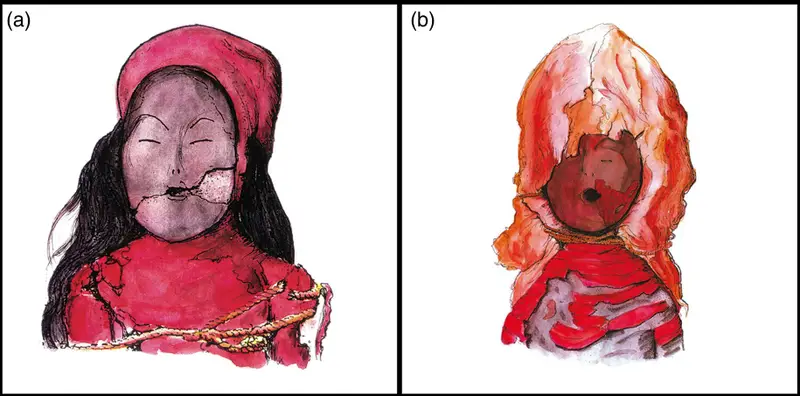

Their mummies are striking not just for their age, but for their complexity. Creating one was a long and deliberate process. The body was carefully taken apart. Internal organs were removed. In some cases, flesh was stripped away entirely. Empty spaces were filled with fibers, clay, and soil. Sticks were used to reassemble and position the body, restoring form where life had ended.

The final step was transformation. The body was coated in a paste made from black manganese, and in later periods, red ocher. Faces were reconstructed. Genitals were reshaped. The dead were not hidden away. They were remade.

For generations, scholars have debated where this practice came from. Some argued it was influenced by outside cultures. Others believed it emerged locally. Dr. Arriaza belongs firmly to the second group, but with a deeply human twist. He proposes that the earliest Chinchorro mummies were created as a form of artistic expression of grief.

The Pain That Would Not Fade

Many of the earliest Chinchorro mummies were children. This is especially true in the Camarones valley, where some of the oldest mummies have been found. The reason, according to the study, may lie in the water the Chinchorro drank every day.

In this valley, water sources contained extremely high levels of toxic arsenic, around 1,000 micrograms per liter, approximately one hundred times the safe limit. Exposure at these levels would have caused severe reproductive health problems. Miscarriages would have been common. Infant mortality would have been devastatingly high.

Nearby valleys did not suffer the same contamination. This uneven exposure may explain why the earliest mummification practices appear concentrated in certain areas.

For families living in small communities, the loss of a newborn was not only emotionally crushing. It could threaten survival itself. Dr. Arriaza explains the weight of this loss directly: “Because we are talking about infant and child mortality, I think parental grief and sorrow were paramount. In a small society, the death of a newborn could threaten a family’s own survival.”

Grief, in this context, was not abstract. It was constant, recurring, and shared.

Turning the Body Into a Canvas

Modern psychology recognizes art therapy as a powerful way to process grief. Creating visual art allows people to express emotions that words cannot carry. Dr. Arriaza suggests something similar may have happened thousands of years ago along the Atacama coast.

“I have been thinking about these ideas for some time, but they take time to develop and polish into hypothetical models. Being at Dumbarton Oaks gave me the opportunity to delve into the multiple aspects of artistic expression—especially art therapy—as a way to help assuage grief,” he explained.

In his view, the Chinchorro did not simply preserve bodies. They transformed them into emotional objects. “It has been a slow process of sorting through my thoughts to explain the Chinchorro’s early, complex, and creative treatment of the dead—children in particular. The transformed body became a canvas for expressing emotion, and a place where these ancient people may have found emotional healing and comfort. They venerated their departed as visual icons.”

Rather than letting death erase presence, the Chinchorro may have used art to keep their loved ones close. The mummies symbolically remained part of the community, bridging the gap between life and loss.

In recent years, scholars have increasingly recognized Chinchorro mummies as works of art. They have even been referenced as such in the Atlas of World Art. This recognition strengthens the idea that mummification was not just a technical process, but a creative one.

When Healing Came at a Cost

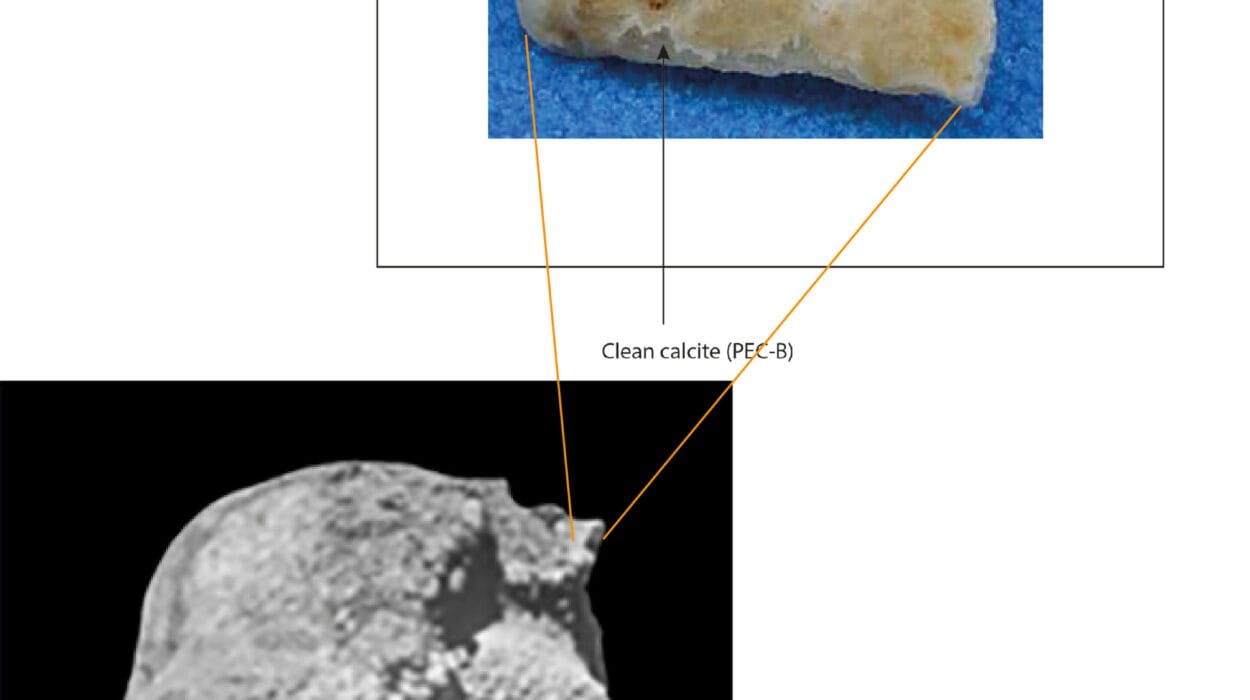

The same materials that helped give form and meaning to grief may also have carried hidden dangers. During the period known as the black mummy tradition, the Chinchorro coated bodies with manganese oxide paint. Over time, this practice may have exposed those involved in mummification to harmful levels of manganese.

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy analysis has revealed elevated manganese concentrations in many Chinchorro individuals. This suggests chronic and excessive exposure, likely through repeated contact with the pigment during mortuary rituals.

Such exposure can lead to a condition known as manganism, a Parkinson-like syndrome. Its symptoms include hallucinations, compulsive behavior, physical pain, difficulty walking, pathological laughter, and a loss of facial expressions resulting in a fixed gaze.

If the Chinchorro experienced these effects, they may eventually have recognized that something was wrong. Dr. Arriaza suggests this awareness could explain a major shift in their mortuary practices. Over time, the use of manganese declined, and red ocher became more common. The black mummies faded from tradition, replaced by red ones.

Changing Hands, Changing Meanings

Dr. Arriaza’s hypothesis goes further, suggesting that shifts in materials may reflect shifts in social roles. During the black mummy period, roughly between 6000 and 4750 years before present, women may have led the mummification process. Their close bonds with deceased infants, formed through pregnancy and early care, may have placed them at the center of these early rituals.

Later, during the red mummy period, between about 4500 and 4000 years before present, the focus of mummification appears to have changed. Visibility, competition, and territorial demarcation became more prominent. Dr. Arriaza suggests that men may have taken a larger role during this time.

These ideas remain hypotheses, but they open new paths for research. As Dr. Arriaza notes, “As new bioarchaeological evidence emerges, we should continue examining sex ratios in mortuary contexts and body preparation, while also paying closer attention to grave goods and increasing microanalytical work on contaminants that may be associated with specific activities.”

Why This Ancient Story Still Matters

This research matters because it challenges how we think about the origins of culture, art, and ritual. It suggests that some of humanity’s most complex traditions may not have begun with power or belief systems, but with love and loss.

By viewing Chinchorro mummification as a response to grief, the study brings ancient people emotionally closer to us. It reminds us that sorrow, care, and the need to remember are not modern inventions. They are deeply human traits that stretch back thousands of years.

The Chinchorro did not have written language, but through their mummies, they left behind a record of feeling. Their transformed bodies tell a story of parents who refused to let death be the end of connection, who used creativity to endure pain, and who turned mourning into meaning.

In understanding this, we do more than learn about the past. We recognize ourselves in it.

More information: Bernardo Arriaza, The Artistic Nature of the Chinchorro Mummies and the Archaeology of Grief, Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1017/s095977432510022x