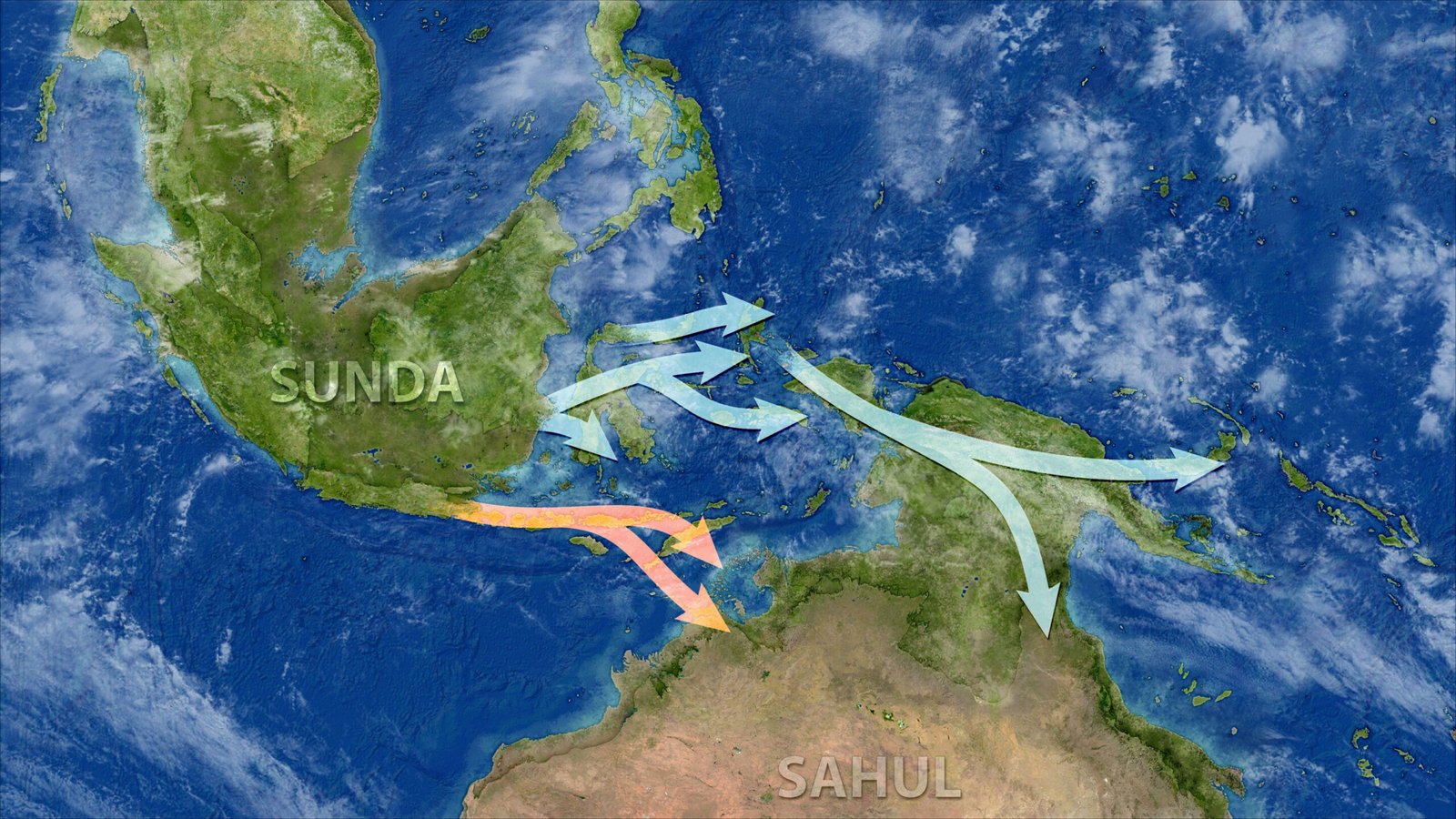

Long before maps, compasses, or recorded history, the world looked very different. During the last Ice Age, when sea levels were far lower than today, New Guinea and Australia were not separate lands divided by water. They were joined as a single vast continent known as Sahul. Forests, plains, and coastlines stretched uninterrupted across what is now open sea. Somewhere far away, modern humans had already begun their long journey outward from Africa, carrying with them not only tools and fire, but curiosity, resilience, and an instinct to explore.

For decades, scientists have argued over when and how those people first reached Sahul. The question is not a small one. It touches the origins of seafaring, the earliest chapters of maritime mobility, and the deep ancestry of Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans. Now, a collaboration between researchers in the United Kingdom, Europe, and Australia has brought new clarity to that ancient crossing, offering a story that reaches back roughly 60,000 years and reshapes how we understand the first ocean voyagers.

Following Traces Written Inside Living Cells

The research was led by maritime archaeologist Professor Helen Farr at the University of Southampton, alongside Professor Martin Richards and the Archaeogenetics Research Group at the University of Huddersfield. Their collaboration brought together archaeologists, geneticists, earth scientists, and oceanographers, weaving multiple lines of evidence into a single narrative of human movement.

Rather than relying solely on stone tools or coastal sites, the team turned to a quieter archive of history: mitochondrial DNA. This DNA lives inside the mitochondria, the tiny energy-producing structures inside our cells. Unlike most genetic material, mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from mothers. Because of this, small changes that accumulate over generations form a record of maternal ancestry that can be traced far back in time.

By comparing how mitochondrial DNA differs among people today, scientists can reconstruct genealogical trees and estimate when populations diverged from one another. This method does not look at bones or artifacts directly. Instead, it reads the story written inside living people and works backward, step by step, generation by generation.

A Debate That Has Divided the Past

Before this study, the scientific community was split between two competing timelines for the settlement of Sahul. One camp supported what is known as the long chronology, proposing that modern humans first arrived around 60,000 years ago. The other camp argued for a short chronology, placing the first arrival much later, around 45,000 to 50,000 years ago.

This debate has persisted partly because Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans have inhabited Sahul for tens of thousands of years, with many Aboriginal Australians understanding that they have always been on country. Western scientific methods, however, have struggled to pin down precise dates and routes for those earliest journeys.

Recent genetic studies had begun to favor the short chronology, suggesting that earlier settlers might have been replaced by later waves of migration. But archaeological and fossil evidence in Southeast Asia and Australia has long pointed to a much earlier presence of modern humans, dating to at least 60,000 years ago. Reconciling these lines of evidence has been one of the central challenges in understanding humanity’s deep past.

Building a Family Tree of the Ancient World

To address this, the team analyzed nearly 2,500 mitochondrial DNA genomes from Aboriginal Australians, New Guineans, and people living across Southeast Asia and the western Pacific. Using these data, they constructed a detailed genealogical tree, tracking how maternal lineages branched and spread from region to region.

DNA changes gradually over time. By measuring the rate at which these changes occur, a method known as the molecular clock, scientists can estimate when different lineages emerged. To ensure accuracy, the researchers checked their clock against islands in the Remote Pacific where colonization times are already well understood. This comparison relied on data from a recent study published in Scientific Reports, led by Dr. Pedro Soares of the University of Minho and involving both Professor Richards and Professor Farr.

The results were striking. Mitochondrial DNA clearly showed that there was only one main successful migration of modern humans out of Africa, dated to about 70,000 years ago. From there, the trail led eastward.

Sixty Thousand Years Ago, Across the Water

The most ancient mitochondrial lineages found among Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans, and nowhere else in the world, dated to around 60,000 years ago. This finding firmly supported the long chronology, placing the first settlement of Sahul far earlier than some recent genetic arguments had suggested.

Tracing these lineages backward revealed their roots in Southeast Asia. Most originated in more northerly regions, such as northern Indonesia and the Philippines. A significant minority, however, traced back to southern Indonesia, Malaysia, and Indochina. This pattern suggested that there were at least two distinct dispersal routes into Sahul.

Both routes appear to have been used at roughly the same time. The northern route gave rise to lineages spread across both New Guinea and Australia, while the southern route produced lineages found only in southern Australia. Together, they paint a picture of early humans navigating complex coastal and maritime landscapes, capable of crossing water gaps and adapting to new environments with remarkable skill.

Testing the Story Against Every Clue Available

The researchers did not rely on mitochondrial DNA alone. They tested their conclusions against Y-chromosome data, which traces paternal ancestry, as well as genome-wide data inherited from both parents. They also compared their genetic findings with archaeological evidence, paleogeographical reconstructions, and environmental data.

One limitation of genetic research in this region is the scarcity of ancient DNA. In tropical environments, DNA rarely survives long enough to be recovered from human remains. Although the team did recover DNA from an archaeological sample dating to the Indonesian Iron Age, this material was too recent to shed light on the earliest settlement of Sahul. It did, however, suggest ancient migrations back westward from New Guinea into Indonesia, hinting at long-term movement and interaction across the region.

Despite these challenges, the overall picture remained consistent. The genetic evidence aligned well with archaeological and environmental data pointing to an early arrival of modern humans in Sahul.

Challenging a Growing Scientific Trend

In recent years, many geneticists have leaned toward the short chronology, largely because of studies re-dating when Neanderthals interbred with the ancestors of modern non-Africans in the Middle East. Since all non-Africans carry about 2% Neanderthal DNA, some researchers argued that this interbreeding must have happened less than 50,000 years ago. If that were true, then the ancestors of Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans, who also carry Neanderthal DNA, could not have arrived in Sahul earlier than that.

However, this creates a conflict. Archaeological and fossil evidence places modern humans in Southeast Asia and Australia at least 60,000 years ago. To reconcile this, supporters of the short chronology have suggested that the earliest settlers were completely replaced by later populations.

The new findings offer a different interpretation. Instead of being wiped out, those first pioneers appear to be the direct ancestors of today’s Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans.

Professor Richards explained the significance clearly, saying, “We feel that this is strong support for the long chronology. Still, estimates based on the molecular clock can always be challenged, and the mitochondrial DNA is only one line of descent. We are currently analyzing hundreds of whole human genome sequences—3 billion bases each, compared to 16,000—to test our results against the many thousands of other lines of descent throughout the human genome.

“In the future, there will be further archaeological discoveries, and we can also hope that ancient DNA might be recovered from key remains, so we can more directly test these models and distinguish between them.”

A Story of Skill, Memory, and Deep Heritage

For Professor Farr, the findings resonate far beyond genetics. They speak to the ingenuity and maritime expertise of early humans who crossed open water tens of thousands of years ago. These were not accidental drifters but skilled voyagers, capable of planning, navigation, and survival in unfamiliar lands.

“This is a great story that helps refine our understanding of human origins, maritime mobility and early seafaring narratives,” she said. “It reflects the really deep heritage that Indigenous communities have in this region and the skills and technology of these early voyagers.”

Why This Research Matters Now

This research matters because it restores depth and continuity to the human story in Sahul. It supports the idea that Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans are descended from the very first modern humans to reach this part of the world, arriving around 60,000 years ago and remaining connected to the land ever since.

It also reshapes our understanding of early seafaring, showing that maritime mobility was not a late development but a defining feature of human expansion. Long before written history, people were already reading coastlines, crossing water, and carrying culture across vast distances.

Most of all, the study reminds us that science is not just about dates and data. It is about listening carefully to many kinds of evidence and respecting the deep time embedded in living communities. By combining genetics, archaeology, and environmental science, this research brings us closer to understanding not just when humans arrived in Sahul, but who they were, how they traveled, and why their legacy still matters today.

More information: Francesca Gandini et al, Genomic evidence supports the “long chronology” for the peopling of Sahul, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ady9493