It’s not often that the dead speak as clearly as they do through a bed burial.

Beneath the quiet soil of European landscapes, from the wooded hills of southern Germany to the windswept plains of East Anglia, a rare and elegant form of burial took shape during the early medieval centuries. The dead were laid not on cold stone or in bare earth, but on wooden bed frames—sometimes richly adorned, sometimes modest, always deliberate. Now, a new study is helping to decode this enigmatic funerary practice, revealing that beneath its surface lies a complex story of cultural exchange, regional tradition, gender, and even long-distance migration.

Dr. Astrid Noterman, an archaeologist with a passion for piecing together the unspoken customs of early medieval Europe, has taken on the monumental task of comparing bed burials across three regions: Germany, England, and Scandinavia. Her findings, recently published in the European Journal of Archaeology, are reshaping how historians understand this rare and captivating mortuary practice.

The conclusion? Bed burials were not a single, monolithic tradition. Instead, they were a web of related but distinct rituals, deeply influenced by local customs, available materials, and perhaps most intriguingly—by the origins and lives of the deceased themselves.

Beneath the Fields of Germany: The Elegance of Simplicity

In the heart of southern Germany, in places like Oberflacht and Trossingen, archaeologists have long puzzled over bed burials that dot ancient cemeteries with little outward sign of distinction. No grand markers. No imposing mounds. And yet, beneath the earth, quiet acts of reverence took place.

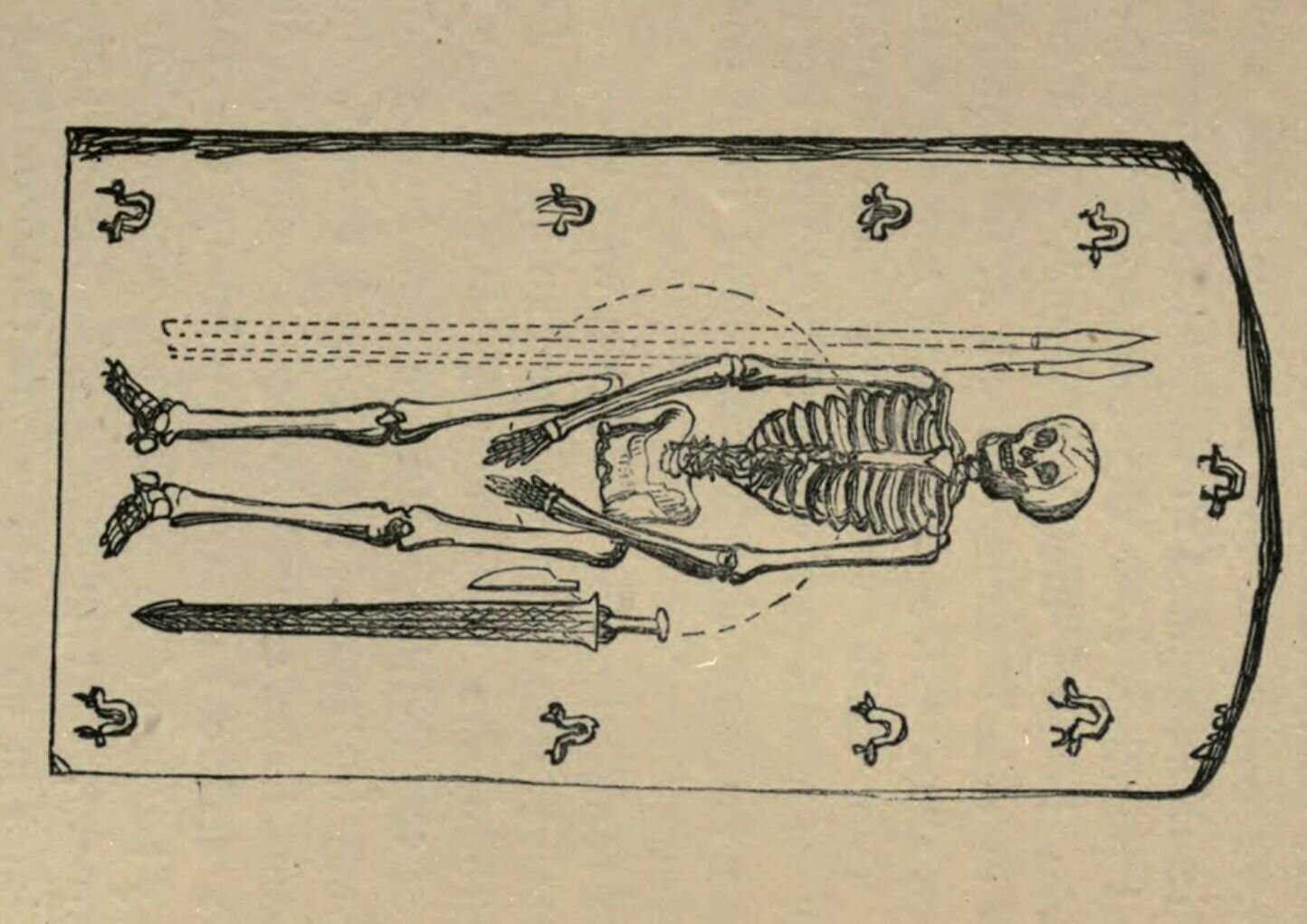

The German tradition, as Dr. Noterman observed, leaned toward humility and uniformity. A wooden bed frame—often remarkably well-preserved—was placed inside the grave, supporting the body of the deceased like a final cradle. Grave goods, when included, were modest: a wooden bowl, a metal ring, perhaps a personal comb.

But some graves hinted at more. A lyre, the instrument of a bard. A candelabra, casting symbolic light. A double chair, evoking companionship or ceremonial status. These details spoke volumes about the lives once lived—and the meaning attached to death.

Interestingly, both men and women were buried this way, though female graves frequently featured weaving tools: spindle whorls, needles, distaffs. It was as if these women were not just being laid to rest, but honored for the roles they played in the fabric of daily life. In this tradition, there was dignity in domesticity.

England’s Ancient Mounds and Migrant Queens

Crossing the English Channel brings us to a very different vision of the dead.

In Anglo-Saxon England, bed burials were rarer, and their settings more eclectic. Some were found in organized cemeteries; others, intriguingly, were placed inside ancient burial mounds—structures that predated them by centuries, possibly millennia. The reuse of such sites suggests a deep reverence for the past, or perhaps a desire to claim ancestral legitimacy through physical connection to ancient landscapes.

Unlike in Germany, English bed burials typically involved dismantled beds. Instead of lying atop a wooden frame, the dead were buried with the bed components arranged around them—planks, posts, and even decorative fittings.

Most striking of all, these burials overwhelmingly belonged to women. And they weren’t just local women.

Stable isotope analysis—an advanced technique that traces where a person grew up based on the chemistry of their bones—revealed that many of these women were not native to the British Isles. At sites like Edix Hill and Trumpington, the chemical signatures told a different story: these women had grown up in continental Europe, possibly in what is now Germany or France.

Were they nobles? Brides brought across the sea to secure alliances? Religious figures? The answers remain speculative. But their foreign origins, paired with the richness of their burials, suggest that these were women of status, power, and perhaps influence—migrants who brought not only their lives but their burial traditions with them.

The Viking Drama of Scandinavian Bed Burials

Then, far to the north, in the fjord-laced coastlines of Scandinavia, the bed burial reaches its most dramatic form—transforming from personal ritual into grand spectacle.

Here, bed burials were not quiet or hidden. They were monumental. They were meant to be seen.

The ship burials at Oseberg and Gokstad are legendary in archaeological circles. At Oseberg, two women were laid to rest in a richly carved ship surrounded by a bounty of grave goods—tapestries, carts, animals, tools, even board games. One of the women, recent research suggests, may have journeyed from the distant Black Sea region, adding yet another twist to the story.

In Scandinavia, bed burials were not part of everyday cemeteries. They were singular, monumental events. Ships served as both transportation and tomb, and the beds within them were thrones of memory. Unlike the more private traditions of Germany or England, Scandinavian burials embraced spectacle, status, and visibility. They were placed near trade routes, along waterways, where passing ships could see them—reminders that the dead still mattered, still held sway.

Children of the Bed

Beyond gender, Dr. Noterman’s study uncovered another fascinating pattern: the treatment of children.

In Germany, children buried in bed graves were typically quite young—between three and seven years old. In England, the age range skewed older, from thirteen to eighteen. This difference could point to variations in cultural views about childhood, status, or even religious beliefs regarding the age of maturity.

These young burials were rare but telling. They suggest that bed burials were reserved not merely for the elite, but for those considered special, marked in life or death. In England especially, where some of these children were also migrants, the implication is profound: youth alone was not the defining factor. Identity, lineage, and perhaps destiny played a role.

A Practice That Traveled With People

Perhaps the most haunting insight of all from Dr. Noterman’s study is the idea that bed burials may not have originated in one place—but followed people across landscapes, carried like heirlooms of ritual.

In Germany, they appear deeply rooted, practiced among local communities. But in England and Scandinavia, the evidence increasingly points to migrants bringing the tradition with them.

Whether these were brides forging alliances, religious leaders on missionary paths, or individuals fleeing upheaval, they brought with them not only language and culture—but beliefs about how to honor the dead. And those beliefs took root in new soils, mingling with local customs to create new forms.

Uncovering the Humanity in Death

Dr. Noterman’s work offers more than an archaeological catalog—it opens a door to empathy across time.

In the quiet logic of bed burials, we see medieval Europeans grappling with the same things we do today: how to remember, how to honor, how to mark the passage from life to whatever lies beyond.

They remind us that death was not just an ending, but a statement. And that those statements—crafted in wood, woven with thread, framed by landscape—still speak across centuries.

Reference: Noterman, A. A. Sharing a Bed but Nothing Else: Bed Burial Traditions in First Millennium AD Europe. European Journal of Archaeology (2025) DOI: 10.1017/eaa.2025.10009