Across deserts, forests, plains, and mountains, beneath layers of soil and stone, lie silent testimonies of human history: ancient burial sites. They are not merely graves but messages from the past, carefully constructed echoes of how our ancestors understood life, death, and what they believed lay beyond. Each burial, whether a grand monument or a humble pit, tells a story—not only of the individuals interred but of entire cultures, their fears, hopes, and spiritual landscapes.

Archaeology has shown that the way humans bury their dead is one of the clearest windows into early beliefs. Burial sites reveal that humans were not content to let death simply be an end; instead, they grappled with it through ritual, symbolism, and architecture. They buried their loved ones with tools, food, ornaments, and sometimes sacrifices—gestures that point to a profound awareness of mortality and an enduring belief in something beyond it.

The First Signs of Burial

The act of burying the dead is not unique to modern humans. Evidence suggests that even our close relatives, the Neanderthals, practiced intentional burials. In sites like Shanidar Cave in Iraq, skeletons have been found carefully arranged, some with traces of pollen that suggest flowers may have been placed with the deceased nearly 60,000 years ago.

Such practices imply that early humans and hominins recognized death as significant, something requiring ritual. Burial marked a departure from leaving bodies exposed to the elements. It suggests reverence, perhaps grief, and likely an idea—however undefined—of a continuation beyond death. These earliest burials are the seeds of human spirituality, the first archaeological evidence of beliefs that death was not simply an ending but a passage.

The Language of Grave Goods

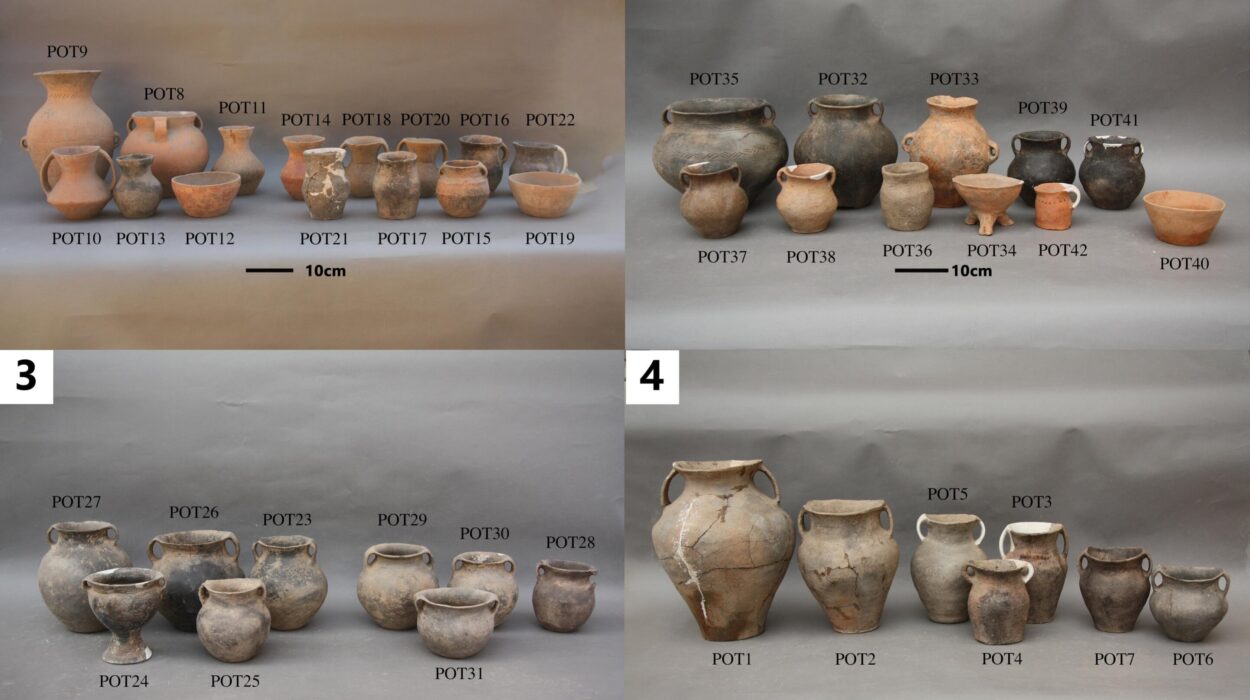

One of the most striking features of ancient burial sites is the inclusion of grave goods—objects buried alongside the dead. These range from simple tools to extravagant treasures and tell us about both the living and the dead.

In Upper Paleolithic Europe, for example, individuals were buried with ornaments, beads, and tools. The famous “Red Lady” of Paviland in Wales (actually the remains of a young man, buried about 33,000 years ago) was interred with mammoth ivory jewelry and covered in red ochre. Red ochre, used widely across early burials, may have symbolized life, blood, or rebirth, hinting at the hope of renewal after death.

The practice of including grave goods suggests that the living believed the dead had needs in an afterlife. Weapons, food, pottery, and jewelry may have been offerings to accompany them into another realm. Such rituals are evidence of complex thought: an imagination that life extended into an unseen world, and that human bonds and possessions carried meaning beyond the grave.

Megalithic Monuments and the Rise of Collective Memory

As human societies grew, burials became larger and more elaborate, often serving not just individuals but entire communities. The Neolithic period, beginning around 10,000 years ago, marked a dramatic shift in burial traditions with the rise of megalithic monuments—massive stone structures built for the dead.

Sites like Newgrange in Ireland, Stonehenge in England, and Carnac in France were not only tombs but cosmic markers, aligned with the movements of the sun, moon, and stars. Newgrange, for example, is oriented so that on the winter solstice, sunlight floods its inner chamber—a powerful symbol of death and rebirth, darkness giving way to light.

These monuments were not simply graves; they were sacred landscapes that bound communities together through ritual and memory. They transformed burial from a private act into a collective experience, embedding the dead within the rhythms of nature and the cosmos. Early beliefs became not just personal but communal, linking human life with celestial cycles and eternal time.

Ancient Egypt: Death as a Continuation

No civilization embodies the complexity of burial practices more than ancient Egypt. To the Egyptians, death was not an end but a continuation of life in another world, provided one was properly prepared. Burial was therefore central to their culture, a sacred science intertwined with religion, architecture, and art.

From the modest tombs of commoners to the majestic pyramids of pharaohs, Egyptian burial practices reveal a belief in the afterlife as a mirror of earthly existence. The dead were provided with food, tools, amulets, and texts such as the Book of the Dead, which contained spells to guide them through the challenges of the underworld.

Mummification itself was a testament to their belief in preserving the body for eternity. The Ka (spiritual essence) and Ba (personality) were believed to need a preserved vessel to continue their existence. The grandeur of the pyramids, aligned with cardinal directions and celestial bodies, reflects a cosmology in which death was part of a divine order, connecting mortals to gods and stars.

Mesopotamia: Death in the Land Between Rivers

In Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization, burial practices reveal a different perspective on death. Unlike the Egyptians, who envisioned a glorious afterlife, the Sumerians and Babylonians often imagined a darker realm. The dead were believed to dwell in a shadowy underworld, a place of dust and silence.

Yet burials in Mesopotamia were rich with meaning. Excavations at the Royal Cemetery of Ur, dating to around 2500 BCE, revealed tombs filled with extraordinary treasures: gold, lapis lazuli, musical instruments, and even sacrificed attendants. These elaborate burials suggest that rulers and elites expected to carry their wealth and status into the afterlife.

Ordinary burials, however, often took place beneath homes, connecting families to their ancestors. This practice reflects a belief in continuity between the living and the dead, in which the deceased remained part of daily life, guardians of the household.

The Indus Valley and the Mystery of Simplicity

The Indus Valley Civilization, flourishing around 2600–1900 BCE, left behind cities of remarkable planning and sophistication, yet their burial practices seem strikingly simple compared to their Egyptian or Mesopotamian contemporaries. Graves contained pottery, ornaments, and occasionally tools, but lacked monumental architecture.

This simplicity raises questions: Did the people of the Indus Valley hold different beliefs about death? Were their rituals less concerned with individual immortality and more with collective memory? The absence of grand tombs suggests a worldview that may have valued equality in death or placed spiritual emphasis elsewhere, perhaps in rituals we cannot fully reconstruct.

China: Ancestors and the Mandate of Heaven

In ancient China, burial practices reveal a culture deeply rooted in ancestor worship and cosmic order. Tombs dating back to the Shang and Zhou dynasties often contained rich offerings of bronze vessels, jade ornaments, and sacrificial victims.

The Chinese believed that ancestors held power in the afterlife, influencing the fortunes of the living. Proper burial and continued offerings ensured harmony between the living and the dead. The elaborate tombs of emperors, such as the mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor with its famous Terracotta Army, reflect not only a desire for protection in the afterlife but also a cosmic mandate. Burial was a way to affirm the ruler’s eternal connection to heaven and earth, legitimizing power even beyond death.

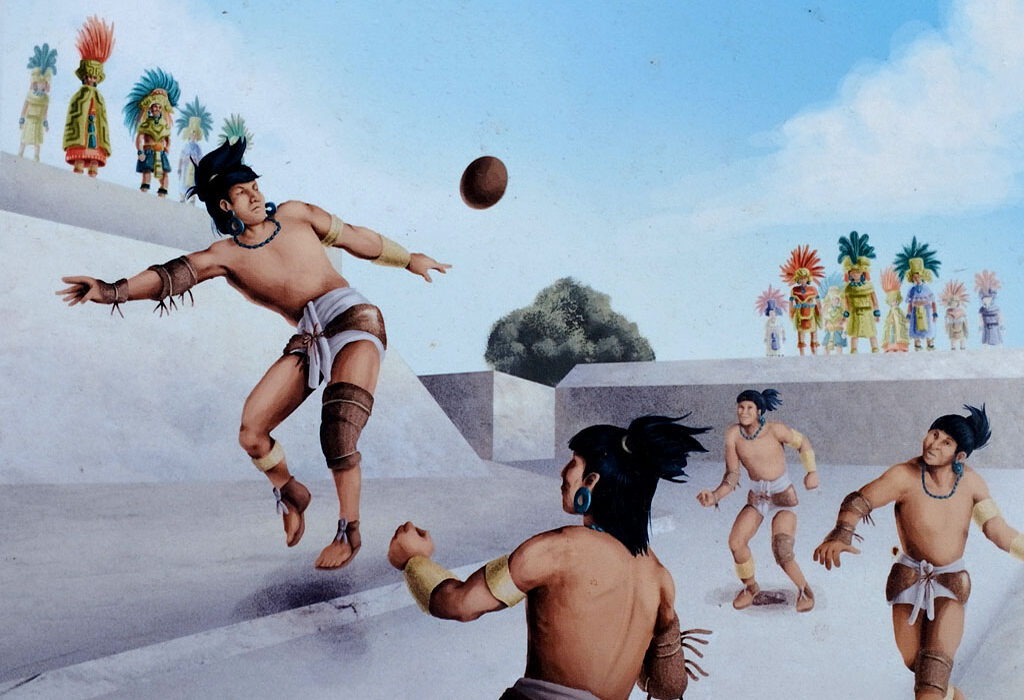

The Americas: Death as Transformation

Across the Americas, ancient burial sites reveal diverse beliefs but often share a common theme: death as transformation. In Mesoamerica, the Maya built elaborate tombs within pyramids, aligning them with celestial events. The dead were often buried with jade, symbolizing life and renewal, and with maize, a sacred crop representing rebirth.

Among the Inca, the dead were mummified and kept as active members of society. Mummies were brought out during festivals, consulted for decisions, and offered food and drink. This reflects a worldview in which the dead did not vanish but remained present, guiding the living.

In North America, burial mounds built by the Adena and Hopewell cultures stand as monuments to communal memory. Grave goods, including shells, copper, and intricately carved stone pipes, suggest beliefs in journeys to other realms and a reverence for the interconnectedness of life and death.

Africa Beyond Egypt: Spirit and Continuity

While Egyptian practices are well known, other African cultures also reveal rich traditions. In West Africa, ancient burials often involved placing the dead in seated positions, sometimes with offerings of food and tools. Such practices emphasize continuity, the belief that the dead remained participants in community life.

The Nok culture of Nigeria, known for its terracotta figures, suggests ritual practices connected to burial, though much remains mysterious. Across sub-Saharan Africa, burial practices consistently highlight reverence for ancestors and a belief that the spiritual world and physical world are intertwined.

Symbols of Rebirth

One of the most persistent themes in ancient burial practices is the symbolism of rebirth. Red ochre, eggs, seeds, and spirals recur across cultures and time, pointing to a shared human instinct: to see death not as final but as part of a cycle.

In many burials, seeds or food were placed with the dead, suggesting nourishment for a journey. Spirals, often carved into tombs, symbolize eternity and the cycles of nature. Fire and light, invoked through lamps or solar alignments, speak to the hope of life continuing beyond darkness. These symbols reveal that early beliefs, though expressed differently across cultures, were united by a common hope: that death leads to renewal.

The Social Meaning of Burials

Burial sites are not only about beliefs in the afterlife but also about life itself. They reflect social structures, hierarchies, and values. Monumental tombs indicate centralized power and wealth, while simple graves suggest communal or egalitarian traditions.

The presence of sacrifices—whether human or animal—points to the weight of belief in ensuring safe passage for the dead. Differences in burial treatment between elites and commoners reveal how societies projected their values into eternity. In every case, burials were as much about the living asserting identity, memory, and continuity as they were about the dead.

Archaeology and the Modern Imagination

For archaeologists, ancient burial sites are among the most valuable windows into past societies. Unlike perishable materials, bones, pottery, and tombs endure, preserving clues about diet, health, ritual, and belief. Through careful excavation and analysis, archaeologists piece together narratives of early human spirituality.

Yet burial sites also stir something beyond science: imagination and empathy. Standing in a tomb thousands of years old, surrounded by the objects chosen with care for someone long gone, one feels the thread of shared humanity. These were people who loved, feared, and wondered—just as we do.

Death, Belief, and the Human Condition

What do ancient burial sites ultimately reveal? That from the earliest times, humans sought to give meaning to death. Whether through flowers in a cave, treasures in a tomb, or monuments aligned with the stars, people have always framed death as more than absence. They envisioned journeys, transformations, and continuities that bound the living and the dead together.

These practices speak to the deepest aspects of the human condition: the need for memory, the yearning for immortality, the fear of oblivion, and the hope for renewal. Burial sites are not only about the dead; they are about life—how people understood themselves, their communities, and their place in the cosmos.

Conclusion: The Eternal Dialogue

Ancient burial sites remind us that belief in life beyond death is one of humanity’s oldest and most enduring ideas. Though cultures differed in expression—from pyramids to mounds, from mummies to ashes—the underlying impulse was the same: to seek meaning in mortality.

Today, we may no longer build megaliths or entomb treasures with our dead, but the questions remain the same. What happens when life ends? Do we continue elsewhere, or do we live on only in memory?

By studying the burial practices of our ancestors, we glimpse the universality of these questions and the creativity with which humans have tried to answer them. Beneath the earth lie not only bones and stones but stories—stories of belief, of love, of fear, and of hope. Ancient burial sites are not just graves; they are dialogues across millennia, whispering that the search for meaning in death is as ancient as humanity itself.