The Roman Empire left its mark in many ways—through its roads, aqueducts, architecture, warfare, and legal systems. But some of its most enduring, intimate traces are those etched not in law or stone architecture, but in the actual stones themselves: Latin inscriptions carved into slabs, monuments, walls, tombs, amphorae, and even the sides of fountains.

They speak not with the lofty voice of emperors alone but also with the laughter of merchants, grief of bereaved mothers, pride of soldiers, and whispered prayers of slaves. They are the raw, unfiltered voices of the ancient world—some boasting of victory, others pleading for remembrance, and some simply saying, “I was here.”

Every year, roughly 1,500 of these inscriptions resurface from beneath the soil, dislodged by archaeologists, construction workers, or sheer luck. Each one is a piece of an ancient conversation interrupted by time—and each poses a riddle to modern historians.

Now, in a remarkable fusion of classical study and cutting-edge technology, artificial intelligence is joining the conversation. A new AI tool, Aeneas, designed in part by researchers at Google’s DeepMind and the University of Nottingham, is helping historians decipher, date, and contextualize these fragmented voices with unprecedented speed and precision.

History, Written by Every Hand

Latin inscriptions were far more than ceremonial; they were practical, personal, and ubiquitous. Found in nearly every Roman province, they announced market days, honored local officials, marked graves, cursed enemies, praised gods, and advertised everything from gladiator matches to baked goods. They appear on temples, roads, taverns, military camps, and the walls of homes.

A tile might bear the name of a craftsman. A tombstone might capture a woman’s grief for a lost child. A wall in Pompeii might carry the graffiti of a drunk citizen scrawling his political loyalties in charcoal. A floor mosaic might issue a lighthearted warning: Cave Canem—“Beware of the dog.”

Dr. Yannis Assael, AI researcher at DeepMind and one of the creators of Aeneas, calls these inscriptions “precious.” Not just for what they say, but for who said them.

“What makes them unique,” Assael noted, “is that they are written by the ancient people themselves across all social classes on any subject. It’s not just history written by the elite.”

Yet, the passage of time has not been kind. Many inscriptions are incomplete. Some are broken into several pieces; others eroded by centuries of wind and rain. Most lack any record of their original location or time of origin. And for each one discovered, hundreds more lie buried or unread, waiting.

Deciphering the Fragmented Past

The task of interpreting these inscriptions has always been immense. Scholars must manually compare partial texts to massive collections of previously catalogued inscriptions—often in different formats, spread across distant libraries or museum archives. Understanding just one stone might require weeks of searching through Latin dictionaries, historical atlases, linguistic databases, and archaeological notes.

Thea Sommerschield, a historian and epigrapher at the University of Nottingham, co-created Aeneas alongside Assael. She described studying inscriptions as “solving a gigantic jigsaw puzzle.”

“You can’t solve the puzzle with a single isolated piece,” she explained. “Even though you know its color or shape, you need to find how it connects to others.”

That’s where artificial intelligence comes in.

The Aeneas model, named after the Trojan hero who founded the Roman people in myth, is a generative neural network—a powerful form of AI capable of recognizing complex patterns and relationships across vast data sets. In this case, Aeneas was trained on a staggering corpus: over 176,000 Latin inscriptions, totaling more than 16 million characters. Some entries even included visual data from photographs of the stones themselves.

The AI was fed not just the text of the inscriptions, but their known dates, geographies, and linguistic features. Over time, it began to learn how particular words, phrases, and even grammatical quirks corresponded to specific locations and time periods. Much like a seasoned historian, it started spotting subtle clues—archaic spellings, particular abbreviations, or unusual names—that hinted at an inscription’s origin.

A Machine That Reads Ancient Minds

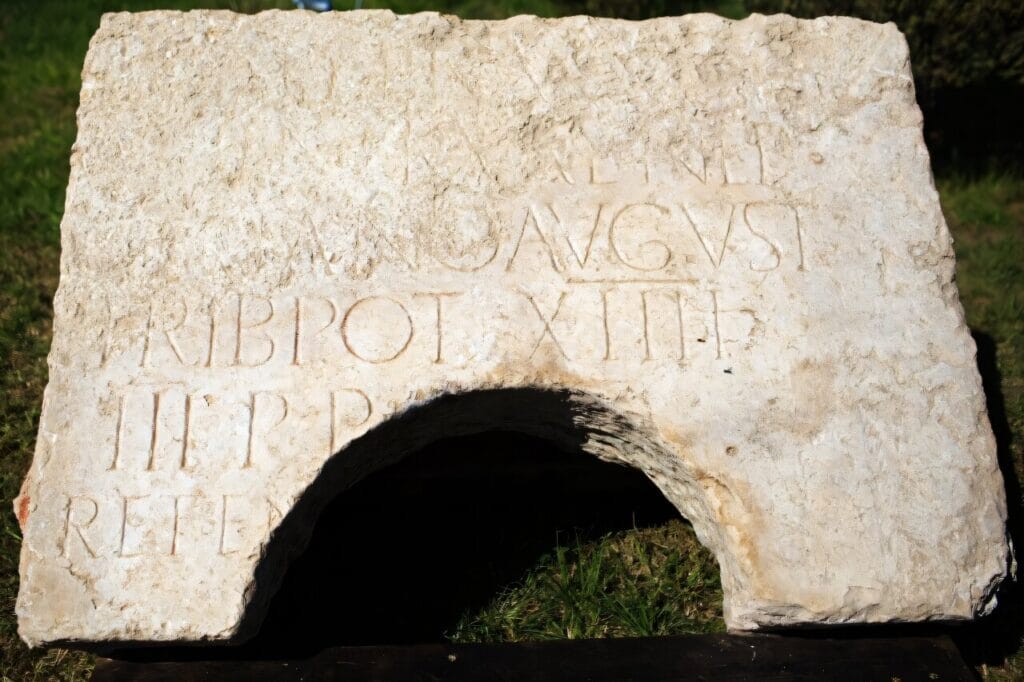

The real test came when Aeneas was asked to analyze one of the most famous inscriptions in Roman history: Res Gestae Divi Augusti, the autobiographical epitaph of Emperor Augustus. Carved into bronze pillars and later copied across the empire, this grand text boasts of Augustus’s deeds and conquests. Yet scholars still debate when precisely it was written, given its mixture of truthful events, political propaganda, and chronological inconsistencies.

Aeneas wasn’t daunted.

Despite the complex, exaggerated style of the text, the AI focused on minute linguistic details and orthographic patterns. It narrowed the origin to two specific decades—exactly the same two periods that historians have long debated.

It was not magic, but math and memory—an understanding built from thousands of similar texts. And when tested across new, unseen data sets, Aeneas still achieved about 80% accuracy in matching inscriptions to time periods and locations, proving that its insights weren’t limited to its training examples.

Humans and Machines, Working Together

But the tool is not meant to replace historians—it is meant to empower them.

When more than 20 Latin scholars used Aeneas during early trials, 90% said it provided valuable leads. It’s not that the AI does their job for them. Rather, it accelerates the grunt work—cutting down hours of archival searches into moments—and highlights connections they might not have otherwise noticed.

“It doesn’t diminish the role of the human researcher,” said Belgian AI specialist Robbe Wulgaert, another co-author of the study. “Instead, it adds a layer of analysis that can support deeper, more informed interpretations.”

In a world where AI often generates anxiety about lost jobs, false information, and plagiarism, Aeneas offers a different vision—one where machine learning doesn’t stifle human insight but helps it flourish. As Wulgaert put it, “This is an example of how generative AI can strengthen, not undermine, the goals of education and scholarship.”

Preserving Fragile Time Capsules

Beyond the scholarly advances, there’s a larger truth hiding beneath this digital tool: it gives voice to those long silenced.

Aeneas helps decode the epitaph of a forgotten child buried in a provincial graveyard. It traces the origin of a brickmaker’s stamp, connecting it to a broader trade network. It identifies where a fragment of a political edict once stood, offering insights into the legal framework of a small Roman town.

Each inscription is a time capsule—a frozen moment of human expression, carved by hands that never imagined a future reader. By reading these fragments, we reach back across two thousand years, not to kings or generals, but to citizens, workers, travelers, and lovers. AI helps reassemble their voices with care and context.

A Future of Deeper Understanding

What’s next for Aeneas and tools like it?

The team behind the project plans to expand the model’s reach, incorporating more image data, different ancient languages, and inscriptions from other cultures—Greek, Aramaic, and beyond. They also aim to make the system more accessible to universities, museums, and even amateur historians.

In time, tools like Aeneas could become part of the standard toolkit for archaeological digs. A newly uncovered fragment in Turkey could be scanned, uploaded, and analyzed within minutes—its context revealed not years later, but on site. That would revolutionize our ability to preserve and understand history in real time.

And perhaps most importantly, Aeneas stands as a reminder that the past is not inert. It speaks. It hums beneath the surface, waiting to be heard again—not in static textbooks or dusty libraries, but in vibrant, digitized voices, interpreted through the combined brilliance of human scholarship and artificial intelligence.

Reference: Yannis Assael, Contextualizing ancient texts with generative neural networks, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09292-5. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09292-5