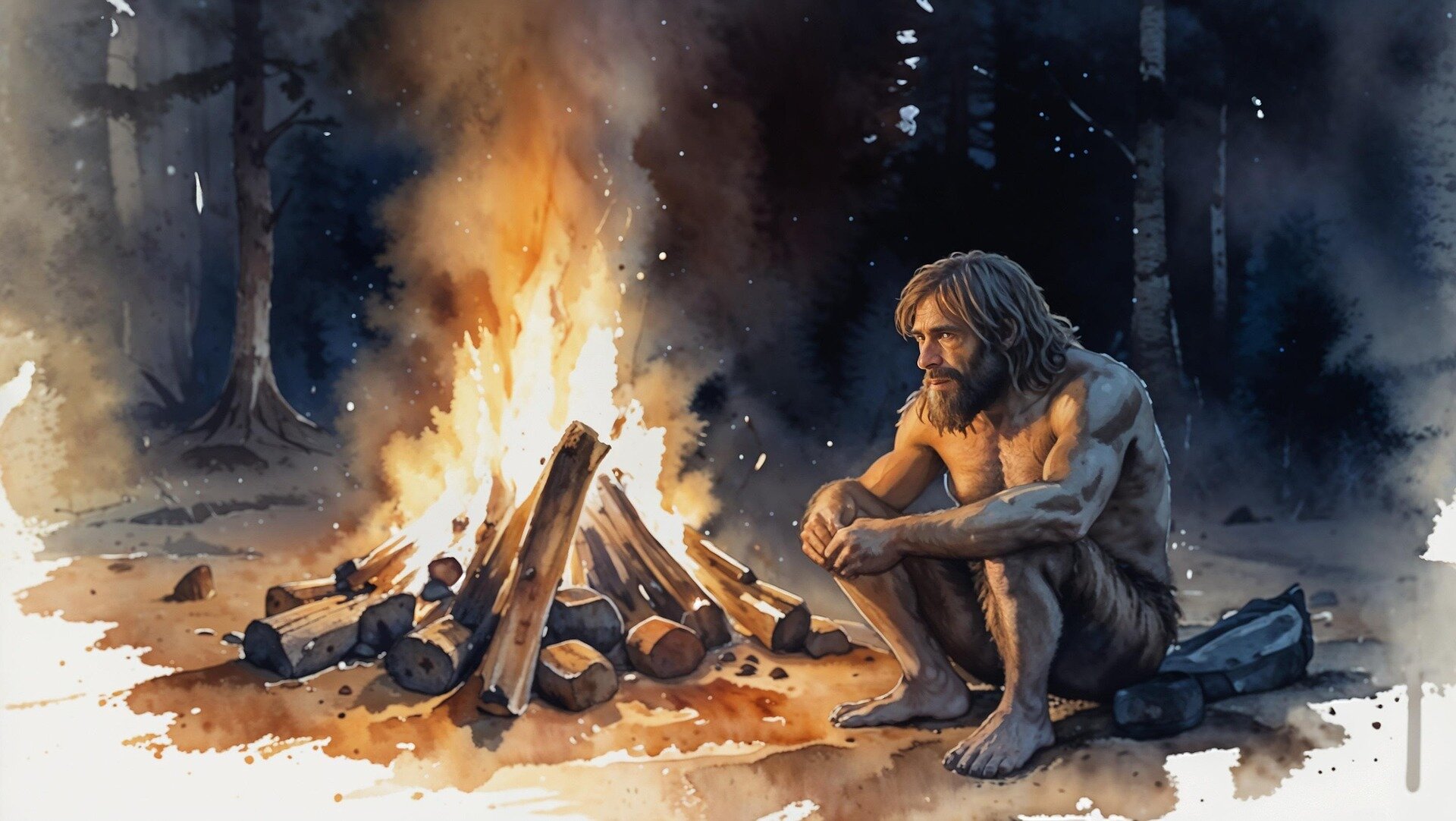

For most living creatures, fire is an absolute boundary. It is something to flee, a danger written deep into instinct. For humans, fire became something else entirely. It warmed our nights, cooked our food, shaped our tools, and quietly entered our daily lives. And with that intimacy came a price that few other species have ever paid: we learned to live with burns.

According to new research, that long and uneasy relationship with high heat may have reached far deeper than culture or technology. It may have reshaped our bodies themselves. Over more than one million years of controlling fire, humans did not just master flames. We were injured by them, survived them, and carried those experiences forward in our biology.

The study suggests that our repeated exposure to high-temperature burn injuries helped sculpt how human skin heals, how our immune systems respond to danger, and why our bodies sometimes spiral into failure after severe burns. Fire, it turns out, may have quietly written part of the human evolutionary story in scars.

A World Where Burns Became Normal

In the natural world, burns are rare. Most animals instinctively avoid fire, and those that encounter it often do not survive. Humans are different. We build fires. We cook over them. We design technologies around intense heat. And across a lifetime, most people experience burns that are small, painful, and survivable.

This pattern is not modern. It likely stretches back to our earliest ancestors who first learned to control fire. From that moment on, burns became a recurring part of human life rather than an occasional catastrophe. No other species regularly experiences burn injuries and survives them.

That difference matters. Evolution responds not just to dramatic events, but to repeated pressures over long periods of time. Small burns, endured again and again across generations, may have created exactly that kind of pressure. The new research argues that natural selection began favoring human traits that helped individuals recover from small to moderate burns, because those individuals were more likely to survive and pass on their genes.

Skin Under Siege

Burns are unlike most other injuries. They damage the skin, the body’s primary barrier against the outside world. When that barrier is breached, bacteria can enter, infections can spread, and the risk grows the longer the wound remains open.

The researchers describe burn injuries as existing along a spectrum. Minor burns often heal on their own, while severe burns can lead to lifelong disability or death. For early humans living without modern medicine, the danger of infection would have been constant, especially when large areas of skin were damaged.

In this context, traits that closed wounds quickly would have been powerful advantages. Faster inflammation, quicker wound closure, and stronger pain signals could all help limit infection and promote survival. Pain, while unpleasant, discourages further injury and forces rest, giving the body time to heal.

Over generations, humans who healed faster from burns likely had better chances of surviving a world shaped by fire. Those traits would spread, slowly becoming part of what made humans biologically distinct.

The Double-Edged Sword of Survival

Yet evolution rarely offers gifts without cost. The same traits that help with small injuries can become dangerous when injuries are large.

The study suggests that the human body’s tendency toward extreme inflammation, heavy scarring, and even organ failure after major burns may be the flip side of adaptations that once improved survival. A system tuned to respond aggressively to injury can spiral out of control when damage overwhelms it.

In other words, our bodies may still be reacting as though they are dealing with a small, survivable burn, even when faced with catastrophic injury. The immune system surges, inflammation intensifies, and the very mechanisms designed to protect us begin to cause harm.

This idea offers a possible explanation for why severe burns in humans can lead to such complex and dangerous complications, even today.

Traces Written in Our Genes

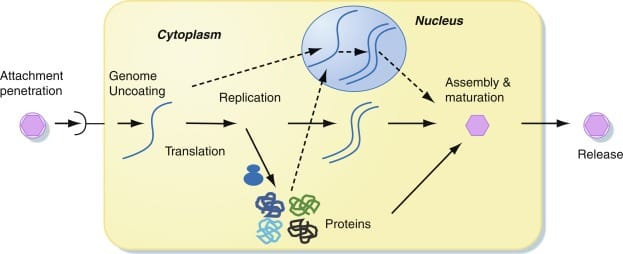

To explore whether this theory left a biological fingerprint, the researchers turned to comparative genomics. By examining genetic data across primates, they searched for signs that certain human genes evolved more rapidly than expected.

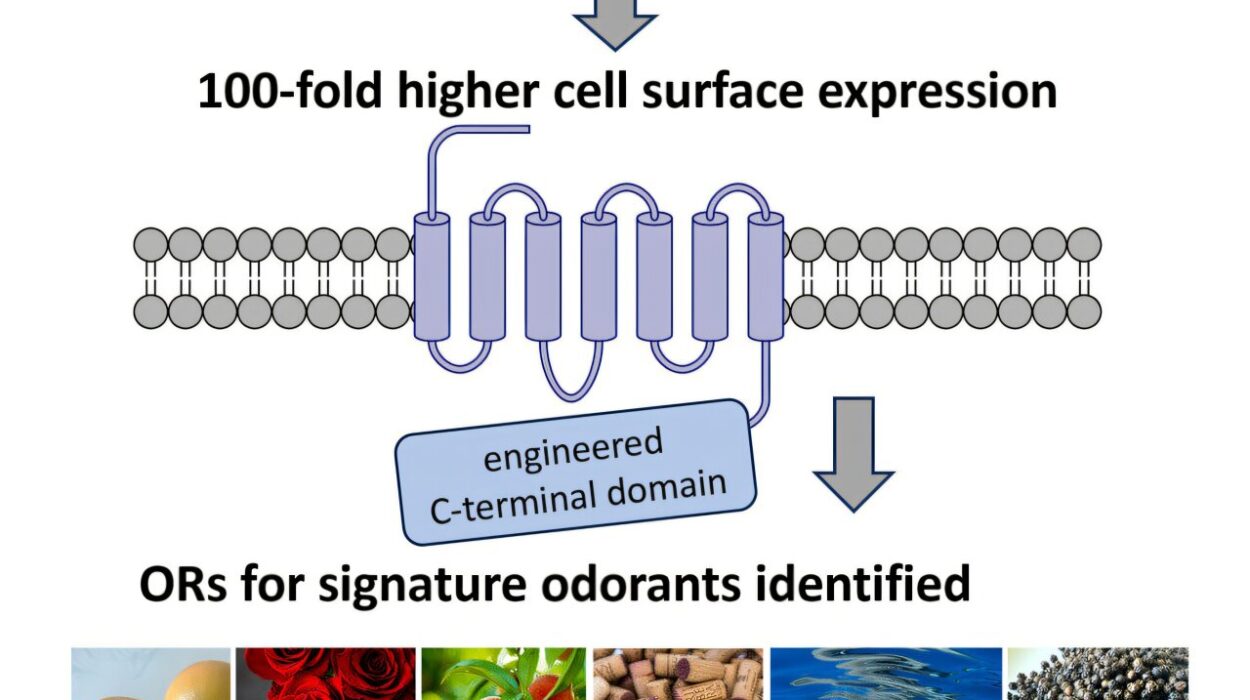

They found exactly that. Several genes involved in wound closure, inflammation, and immune system response showed signs of accelerated evolution in humans. These genes are directly tied to how the body responds to burn injuries, especially the need to rapidly close damaged skin and fight infection.

Before the widespread use of antibiotics, infection was one of the most dangerous consequences of burns. Genes that improved resistance would have been especially valuable. The findings suggest that repeated exposure to burns left a measurable mark in the human genome.

This does not mean burns were beneficial. Rather, survival in a fire-filled world favored bodies that could endure them better than others.

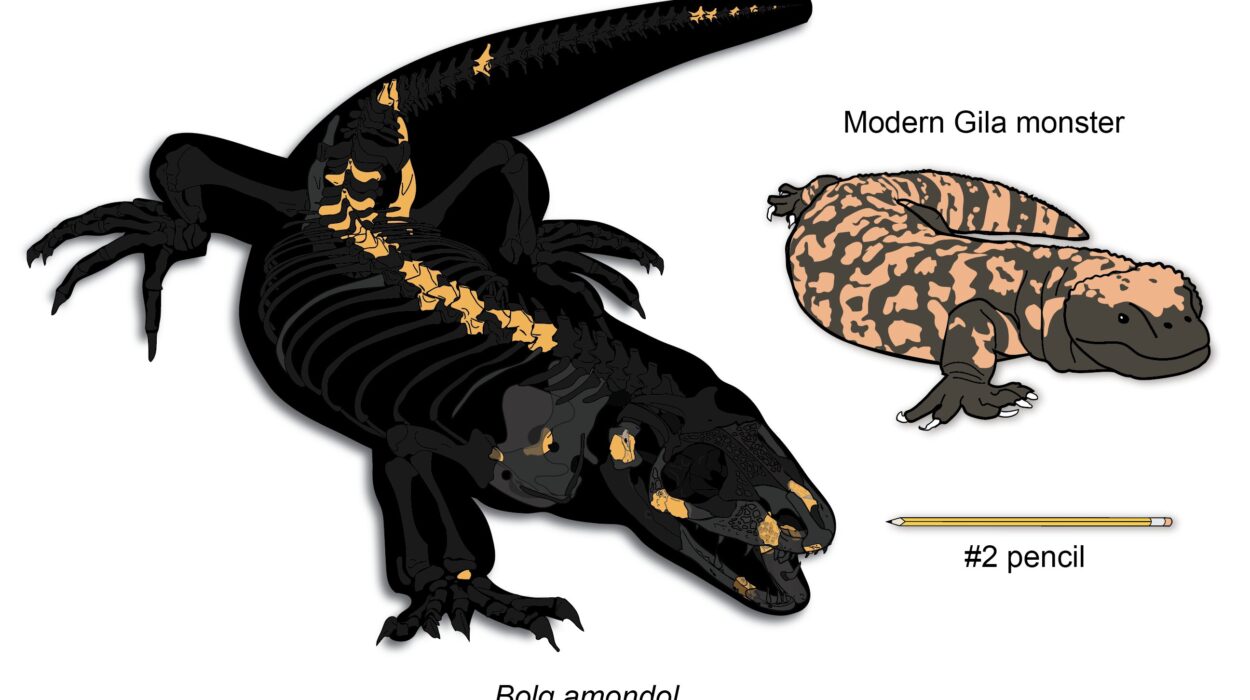

A Uniquely Human Kind of Selection

One of the most striking aspects of this research is the kind of natural selection it describes. Fire is not just an environmental force; it is a cultural invention. Humans created the conditions that exposed them to burns, and evolution responded.

This makes burn-related selection unlike the pressures that shape most species. It depends on behavior, technology, and shared practices passed down through generations. Fire altered human life, and human biology adapted in return.

As one of the researchers notes, this idea adds a new chapter to the story of what makes us human. It suggests that culture and biology have been entwined far longer, and more deeply, than previously understood.

Why Animal Models Fall Short

Burn research has long struggled with a frustrating problem. Treatments that appear effective in animal studies often fail when applied to humans. This new evolutionary perspective may help explain why.

Other animals do not share the same long history of surviving burns. Their bodies did not evolve under repeated exposure to fire. As a result, their inflammatory responses, wound healing processes, and immune reactions may differ in fundamental ways.

If human responses to burns are shaped by unique evolutionary pressures, then animal models may be limited in what they can reveal. Understanding this difference could change how scientists design experiments and interpret results in burn research.

A New Lens on Healing and Scars

The study also opens new questions about scarring and why it varies so widely between individuals. The genetic basis for scarring and tissue response to injury remains poorly understood, but viewing it through an evolutionary lens could offer fresh insights.

If certain genetic traits were favored for rapid wound closure, that may help explain why scarring is sometimes aggressive or unpredictable. Future research could explore how genetic variations influence healing outcomes, potentially explaining why some people recover well while others struggle after similar injuries.

This approach shifts burn research from treating injuries as isolated events to seeing them as part of a long biological history.

Why This Research Matters

This study matters because it reframes something deeply familiar. Burns are not just accidents or medical emergencies. They are a uniquely human experience, woven into our evolutionary past.

By suggesting that fire exposure shaped human genetics, the research helps explain why our bodies respond to burns the way they do, both for better and for worse. It offers a possible answer to why we can survive injuries that would kill other animals, yet remain vulnerable to devastating complications.

Understanding these evolutionary trade-offs could influence how burns are studied, how treatments are designed, and how doctors interpret the body’s reactions to injury. It reminds us that human biology is not optimized for modern medicine, but for survival in a world where fire was both a gift and a danger.

In the glow of our earliest flames, evolution was watching. And in the scars we still carry, its legacy may remain.