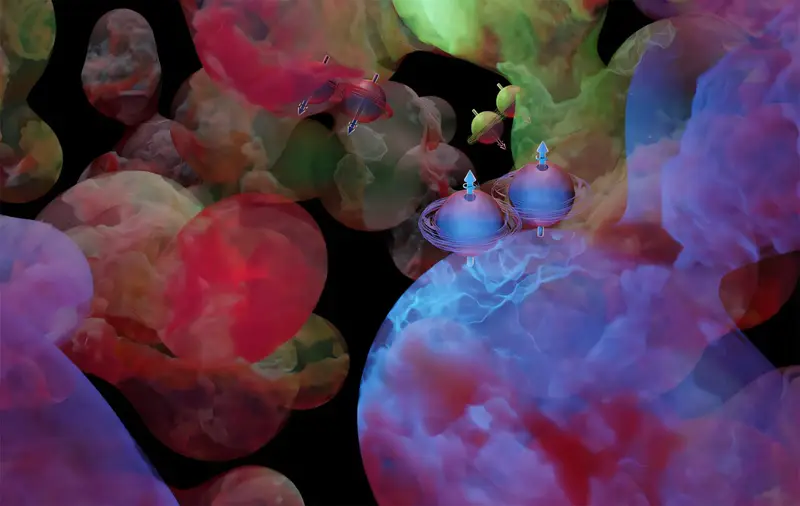

For a long time, the vacuum was imagined as a silent void, a cosmic pause button between bits of matter. But deep inside the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider at Brookhaven National Laboratory, scientists have caught the vacuum doing something far stranger. In violent proton-proton collisions, particles burst into existence carrying a faint but unmistakable memory of a world that existed before they were real. These particles appear to remember the quantum vacuum itself, a place where matter briefly flickers into being and disappears again.

The discovery comes from the STAR Collaboration, working at the U.S. Department of Energy’s flagship nuclear physics facility. Their newly published results in Nature reveal experimental evidence that particles formed in high-energy collisions retain a defining feature of virtual particles, the ephemeral inhabitants of the quantum vacuum. That feature is spin, a quantum property tied to magnetism and intrinsic motion. And the way this spin shows up hints that real matter may be born already shaped by the “nothingness” it came from.

A Vacuum That Seethes With Possibility

Physicists have known for nearly a century that empty space is anything but empty. Even in perfect darkness, the quantum vacuum hums with activity. Energy fluctuations constantly create paired apparitions of particles and antiparticles, known as virtual quark-antiquark pairs. These pairs are entangled, linked so deeply that their properties mirror each other, including their spin. But they exist only for fleeting moments, vanishing before they can be directly observed.

At RHIC, however, conditions are different. When protons collide at enormous energies, the collisions can feed these virtual pairs just enough energy to cross a threshold. The once-invisible becomes real. The question the STAR scientists asked was simple but daring: if virtual particles from the vacuum become real, do they carry any trace of their former, ghostly existence?

Following the Trail of a Subatomic Signature

To find the answer, the team focused on a specific kind of particle called the lambda hyperon, along with its antimatter counterpart, the antilambda. Lambdas are especially valuable to physicists because they come with a built-in clue about their internal spin. When a lambda decays, the direction in which it releases a proton or antiproton reveals how the lambda itself was spinning at the moment of its creation.

Even more important, lambdas contain a strange quark, while antilambdas contain a strange antiquark. In the quantum vacuum, strange quark-antiquark pairs are always born with their spins aligned. Most particles produced in collider experiments do not share this property; their spins point in random directions. If lambdas and antilambdas emerged from collisions with correlated spins, it would suggest a shared origin deep in the vacuum.

Searching for a Whisper in a Storm

Detecting such a signal was anything but easy. In a typical proton-proton collision, countless particles fly out in every direction, their spins largely uncorrelated. The effect STAR was looking for was subtle, a tiny deviation from randomness buried in data from millions of collision events.

As Jan Vanek, who led the data analysis, explained, the challenge was to find rare lambda-antilambda pairs whose spins lined up against overwhelming odds. The team meticulously removed biases and false signals, combing through the data with extraordinary care. What emerged was a result that stunned even seasoned physicists.

When lambdas and antilambdas were produced close together in space, their spins were not just correlated. They were 100% spin aligned.

Quantum Twins Step Into the Light

That perfect alignment mirrored the behavior of virtual strange quark-antiquark pairs in the vacuum. The implication was profound. It meant that the strange quark inside a lambda and the strange antiquark inside an antilambda likely originated as a single entangled virtual pair, long before the particles themselves existed as real matter.

Vanek described the phenomenon with an almost human metaphor. These particles, he said, behave like quantum twins. Born together in the vacuum, they carry a shared identity. When transformed into real particles close to one another, they preserve that ancient bond. Their spins remember where they came from.

This was not an indirect inference or a theoretical exercise. As Zhoudunming (Kong) Tu, a co-leader of the study, emphasized, it was the first time scientists could directly see evidence that the quarks forming detectable particles were emerging from the quantum vacuum itself. The spin alignment survived the chaotic transition from virtual to real, a journey many physicists thought would erase such delicate quantum information.

When Distance Breaks the Spell

The story becomes even more intriguing when those quantum twins are separated. STAR scientists also studied lambda-antilambda pairs that emerged farther apart in the collision aftermath. In those cases, the spin correlation disappeared. The twins seemed to forget each other.

This loss of alignment suggests that interactions with surrounding quarks or the broader environment may disrupt the original quantum connection. Whether this represents a fading of true quantum entanglement or a shift toward a more classical kind of correlation remains an open question. Answering it will require further measurements and deeper exploration.

What is clear is that the experiment captures a rare moment where the quantum world brushes up against the classical one. It shows how fragile quantum connections can be, and how the environment shapes what ultimately becomes the matter we can observe.

A Bridge Between Two Worlds

The implications stretch far beyond a single particle type. The ability to trace real particles back to their origins in the vacuum offers a new way to study the transition from quantum to classical states of matter. This transition lies at the heart of modern physics and underpins emerging fields like quantum information science and quantum-based technologies.

As Tu noted, the physics governing these transitions is universal. Understanding how quantum properties survive, change, or vanish as systems grow larger could inform technologies that rely on controlling quantum behavior before it slips away.

Rewriting the Story of How Matter Forms

At its core, nuclear physics grapples with a fundamental puzzle: how free-moving quarks become bound together to form particles like protons, neutrons, and hyperons. The STAR results introduce a powerful new tool for unraveling this mystery. By studying how virtual particles from the vacuum gain energy and become real, scientists can begin to reverse engineer the process of matter formation.

Tu suggested that the method could be extended to more complex environments, such as atomic nuclei, where quarks experience far richer interactions. By sending these virtual pairs through different nuclear “environments,” researchers could watch how they evolve, how their early connections influence their final properties, and how structure and mass emerge from seemingly empty space.

Looking Toward the Next Frontier

The approach does not end at RHIC. Future experiments involving nuclear collisions and the upcoming Electron-Ion Collider (EIC), planned for Brookhaven, promise even sharper insight. The EIC will allow scientists to probe the relationship between the vacuum and visible matter with unprecedented precision, reusing much of RHIC’s existing infrastructure while expanding its reach.

From the smallest subatomic components to the largest structures in the universe, the same fundamental processes apply. Stars, planets, galaxies, and people are all built from matter that once flickered briefly in the vacuum, balanced on the edge between existence and nonexistence.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research touches one of humanity’s oldest and deepest questions: how something comes from nothing. By showing that particles born in high-energy collisions carry the spin imprint of entangled virtual quarks, the STAR Collaboration has provided a tangible link between the quantum vacuum and the matter that fills our universe.

It reveals that the vacuum is not merely a backdrop but an active participant in creation, shaping the properties of matter before it even becomes real. Understanding this connection does more than advance nuclear physics. It reshapes our picture of reality itself, suggesting that the visible universe is inseparably tied to the restless, invisible fluctuations beneath it. In that sense, every particle around us may still carry a whisper of the nothingness it emerged from, a quiet reminder that emptiness is where everything begins.

Study Details

Janek Uin, Measuring spin correlation between quarks during QCD confinement, Nature (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09920-0. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09920-0