For decades, astronomers have learned to read the universe through light. Radio waves revealed hidden galaxies. X-rays exposed violent cosmic events. Now, a quieter messenger is beginning to speak with direction and intent. An international team of astrophysicists, including researchers from Yale, has built and tested a way to use gravitational waves not just to hear the universe, but to map it.

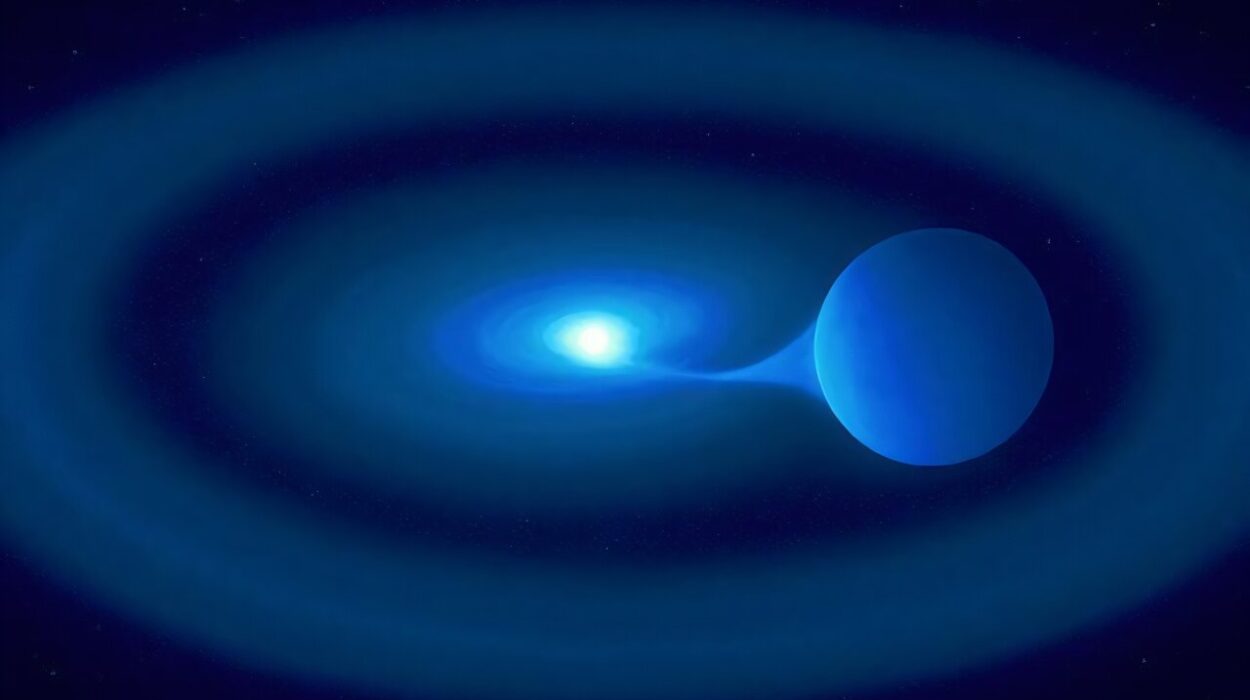

These waves are not flashes or flares. They are subtle ripples in space itself, produced by some of the most extreme objects known: pairs of supermassive black holes slowly spiraling toward each other. Until recently, those ripples blended together into a faint, cosmic hum. Now, researchers say they are learning how to pick out individual voices from the chorus and pinpoint where they come from.

If successful, this effort could reshape how astronomy is done. Just as earlier generations learned to navigate the cosmos through new forms of light, this work hints at a future where gravitational waves become a guiding signal, revealing otherwise invisible structures across the universe.

A Map Built from Ripples, Not Light

The collaboration behind this work is the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves, known as NANOGrav. Their goal is ambitious: to create a map showing where merging supermassive black hole pairs are located across the universe, using only gravitational waves.

This map does not exist yet, but the researchers have taken a crucial step toward it. In a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, they demonstrate a detection protocol that provides concrete benchmarks for identifying individual, continuous gravitational wave sources.

Chiara Mingarelli, an assistant professor of physics at Yale and a member of NANOGrav, describes this moment as foundational. For the first time, the scientific community has a tested framework for developing and evaluating detection methods aimed at specific gravitational wave sources rather than a general background.

Even a small number of confirmed detections, the team explains, would be enough to anchor this new kind of map. With those anchors in place, future observations could steadily fill in the picture, transforming a once-uniform hum into a structured landscape.

The Hum Beneath Everything

This work builds directly on a major milestone reached by NANOGrav in 2023. That year, the collaboration reported the first direct evidence of a gravitational wave background. This background is created by countless pairs of supermassive black holes slowly merging across the universe, each emitting low-frequency gravitational waves that overlap and blend together by the time they reach Earth.

Detecting that background was like realizing you are standing in a crowded room full of quiet conversations. You cannot yet distinguish who is speaking, but you know the voices are there.

The new challenge is to isolate individual speakers. That requires both precision and creativity, because these waves are extraordinarily subtle. The team needed a way to separate individual signals from the background without losing scientific rigor.

Listening with the Help of Dead Stars

To accomplish this, NANOGrav relies on some of the most reliable clocks in the universe: pulsars. Pulsars are the collapsed cores of massive stars that have exploded. As they rotate, they emit radio signals with astonishing regularity.

When a gravitational wave passes between Earth and a pulsar, it slightly alters the timing of those signals. By carefully monitoring many pulsars over long periods, researchers can detect patterns that reveal the presence of gravitational waves.

This pulsar-based approach was key to discovering the gravitational wave background. But for this new work, the collaboration pivoted toward something more targeted. Instead of listening broadly, they began to ask where, specifically, individual waves might be coming from.

Following the Light of Cosmic Beacons

Guidance came from earlier theoretical work led by Mingarelli and her collaborators. That research suggested that black hole mergers are five times more likely to be found in galaxies containing a quasar. Quasars are intensely bright regions powered by gas falling into a black hole, acting like cosmic beacons that mark active galactic centers.

Armed with this insight, the team designed an end-to-end targeted search framework. Rather than scanning blindly, they focused their attention on galaxies already known to host active black holes.

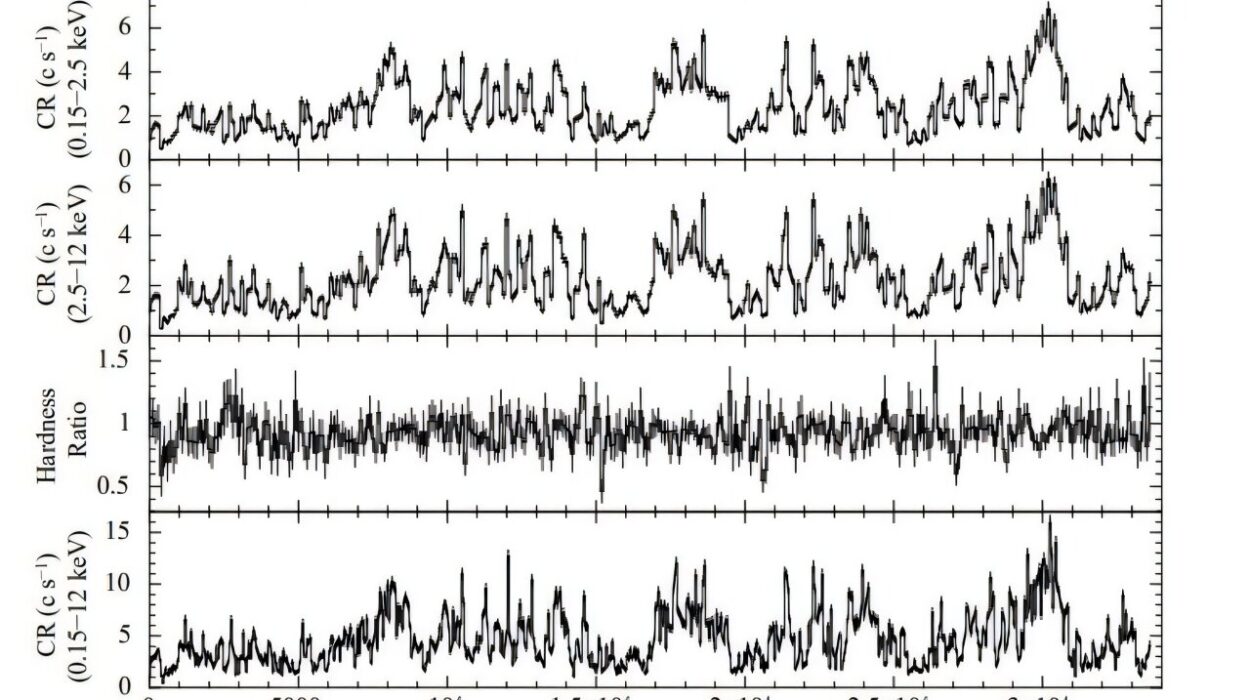

In the new study, Mingarelli and her colleagues combined measurements of the gravitational wave background with variable observations of quasars. They conducted targeted searches within 114 active galactic nuclei, regions at the centers of galaxies where black holes are actively drawing in matter.

This approach brought gravitational waves and electromagnetic observations together in a single, carefully structured search.

Two Signals Rise Above the Noise

From this systematic effort, two candidates emerged as especially compelling: SDSS J1536+0411 and SDSS J0729+4008. Within the team, they are affectionately known as Rohan and Gondor.

The names are more than playful nicknames. Rohan honors Rohan Shivakumar, the Yale student who first analyzed that signal. Gondor followed naturally, inspired by both the sequence of discovery and a moment of shared cultural joy.

In J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings,” the lighting of beacons in Gondor and Rohan signals a call for unity and action. For the researchers, these two candidates felt similar. They stood out like beacons themselves, suggesting places where individual gravitational wave sources might be calling to be understood.

Mingarelli describes the naming as a blend of people and pop culture, a reminder that science is a human endeavor carried out by curious minds working together.

A Roadmap Takes Shape

What makes this study particularly significant is not only the identification of promising targets, but the clarity of the framework behind it. The team did not stumble upon Rohan and Gondor by chance. They followed a rigorous, systematic protocol designed to be tested, refined, and expanded.

This roadmap lays out how future searches for supermassive black hole binaries can be conducted with consistency and confidence. It connects theory, observation, and data analysis into a single pipeline, showing how gravitational wave astronomy can move from detection to detailed exploration.

Mingarelli emphasizes that the work opens doors across multiple areas of astrophysics. It touches gravitational wave theory, advances data analysis techniques, sheds light on galaxy mergers, and deepens our understanding of black hole behavior.

Perhaps most importantly, it shows that individual continuous gravitational wave sources are no longer purely theoretical. They are becoming observable targets.

Why This Quiet Breakthrough Matters

This research matters because it changes what is possible. Until now, gravitational waves from supermassive black holes were something astronomers could sense only in aggregate, as a background presence. This work demonstrates a path toward identifying individual sources and placing them on a map.

Such a map would offer a completely new way to explore the universe. It would allow scientists to study black hole pairs not just as abstract concepts, but as located systems with histories and futures. It would provide a new tool for understanding how galaxies merge, how black holes grow, and how gravity behaves on the largest scales.

Equally important, this achievement shows how careful theory, patient observation, and creative methodology can turn a faint cosmic hum into meaningful information. The universe has been sending these ripples for eons. Now, humanity is learning not only to hear them, but to understand where they come from and why they matter.

As NANOGrav continues identifying and locating black hole binaries in the months ahead, the first outlines of a gravitational wave map are beginning to emerge. The beacons are lit, and a new era of exploration is quietly underway.

Study Details

Nikita Agarwal et al, The NANOGrav 15 yr Dataset: Targeted Searches for Supermassive Black Hole Binaries, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2026). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae3719 iopscience.iop.org/article/10. … 847/2041-8213/ae3719