For decades, astronomers have spoken about the heart of the Milky Way with a kind of hushed certainty. Somewhere deep in the galaxy’s core, hidden behind curtains of dust and distance, sits Sagittarius A*, a supermassive black hole whose gravity commands the frantic motions of nearby stars. It has been treated as a settled fact, a cosmic anchor holding the galaxy together.

But science rarely leaves certainty untouched.

A new study published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society asks a question that feels almost audacious: what if the Milky Way does not have a black hole at its center at all? What if, instead, the galaxy’s core is dominated by something even stranger and more elusive—a massive, compact concentration of dark matter, behaving like a black hole without actually being one?

This idea does not come from speculation alone. It emerges from a careful attempt to explain a puzzle that stretches from the innermost light-hours of the galaxy to its farthest outskirts.

Stars That Dance Too Fast to Ignore

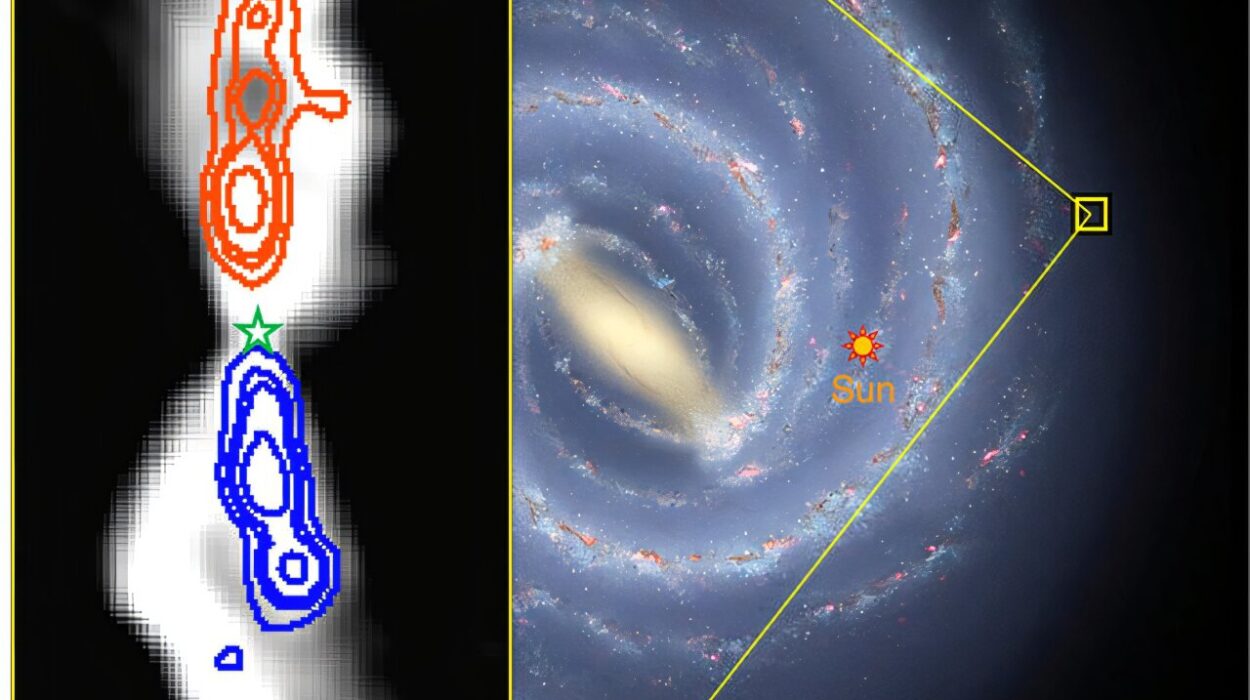

Near the galactic center, a small group of stars known as the S-stars perform a violent celestial ballet. They whip around the core at astonishing speeds, reaching thousands of kilometers per second, completing tight, elongated orbits that seem to demand an immensely strong gravitational pull. For years, these motions have been one of the strongest arguments for a black hole lurking at the center.

Alongside these stars are the enigmatic G-sources, dust-shrouded objects that also orbit perilously close to the galactic heart. Their paths, too, trace the invisible grip of something extraordinarily massive and compact.

Traditionally, the explanation has been simple and powerful: only a supermassive black hole could do this.

The new research does not deny the gravity. Instead, it asks whether gravity alone tells the full story.

A Different Kind of Darkness

The international team behind the study proposes an alternative rooted in the strange physics of fermionic dark matter. Dark matter, the invisible substance thought to make up most of the universe’s mass, has long been invoked to explain why galaxies hold together. Here, the researchers explore a specific version made of fermions, light subatomic particles that follow well-defined quantum rules.

According to their model, this kind of dark matter can naturally arrange itself into a remarkable structure. At the center forms a super-dense, compact core, while farther out it spreads into a vast, diffuse halo. Crucially, these are not separate components but parts of a single, continuous entity.

The inner core, despite not being a black hole, would be so massive and tightly packed that it could mimic the gravitational pull of one. To the S-stars and G-sources racing nearby, the difference would be almost impossible to detect. Their orbits would look exactly as they do in observations.

In this picture, the Milky Way’s heart is not an object swallowing space and time, but a dense knot of dark matter, quietly bending gravity to its will.

When the Galaxy Itself Joins the Story

What makes this proposal especially intriguing is that it does not stop at the center. The same dark matter structure that explains the frantic inner orbits also extends outward, shaping the motion of stars and gas across the entire galaxy.

This is where data from Gaia DR3, the European Space Agency’s detailed stellar survey, becomes essential. Gaia has meticulously mapped how the Milky Way rotates far from its core, tracing the rotation curve of the galaxy’s outer halo.

The data reveal a Keplerian decline, a gradual slowdown in rotational speed at large distances. The researchers found that when their fermionic dark matter halo is combined with the known mass of ordinary matter in the galaxy’s disk and bulge, this slowdown emerges naturally.

This matters because traditional cold dark matter models tend to predict halos with extended, gradually thinning “tails,” described by power laws. The fermionic model, by contrast, produces a more compact halo tail, a tighter structure that aligns with what Gaia observes.

For the first time, the same dark matter framework appears capable of explaining both the galaxy’s calm, distant rotation and its violent central dynamics.

One Substance, Two Faces

Dr. Carlos Argüelles, a co-author of the study from the Institute of Astrophysics La Plata, describes this as a conceptual shift rather than a simple substitution.

“We are not just replacing the black hole with a dark object,” he explains. “We are proposing that the supermassive central object and the galaxy’s dark matter halo are two manifestations of the same, continuous substance.”

In other words, the Milky Way’s dark heart and its sprawling dark halo may be deeply connected, not separate mysteries patched together with different theories. The galaxy could be structured by a single dark component, changing its behavior with distance and density.

This idea bridges scales that are almost unimaginably different, from light-hours near the center to tens of thousands of light-years at the edges.

A Shadow That Looks Familiar

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the model is that it survives one of the most visually compelling tests in modern astronomy: the black hole shadow.

In 2022, the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration released an image of Sagittarius A*, revealing a glowing ring surrounding a dark central region. This shadow-like feature was celebrated as direct visual evidence of a black hole.

Yet a previous study by Pelle and colleagues, also published in MNRAS, explored what would happen if an accretion disk—a swirling disk of hot material—illuminated a dense fermionic dark matter core instead. The result was surprising. The dark matter core cast a shadow strikingly similar to the one observed.

According to lead author Valentina Crespi, this similarity is not a coincidence. The dense core bends light so strongly that it creates a central darkness encircled by a bright ring, closely resembling a black hole’s silhouette.

“Our model not only explains the orbits of stars and the galaxy’s rotation,” Crespi says, “but is also consistent with the famous ‘black hole shadow’ image.”

In other words, even our most iconic image of the Milky Way’s center may not be the decisive proof it once seemed.

Data, Doubt, and the Road Ahead

To test their idea, the researchers statistically compared the fermionic dark matter scenario with the traditional black hole model. At present, the motions of the inner stars alone cannot decisively distinguish between the two. Both explanations remain compatible with existing observations.

What sets the dark matter model apart is its unified framework. It simultaneously accounts for central star orbits, the shadow-like image, and the galaxy’s large-scale rotation without invoking separate ingredients for each phenomenon.

The team emphasizes that future observations will be crucial. More precise measurements from instruments like the GRAVITY interferometer on the Very Large Telescope in Chile could reveal subtle differences in stellar motions. Another promising test involves searching for photon rings, a distinctive feature expected around true black holes but absent in the dark matter core scenario.

These observations could finally tip the balance.

Why This Changes the Way We See the Milky Way

This research matters because it challenges one of the most entrenched ideas in modern astronomy, not by discarding evidence, but by weaving it into a broader, more cohesive story.

If the Milky Way’s center is not dominated by a black hole but by a dense concentration of dark matter, it would reshape our understanding of both galactic evolution and the nature of dark matter itself. The galaxy would no longer be organized around a singular, exotic object, but around a continuous substance that quietly sculpts structure on every scale.

It would also remind us that even the most dramatic cosmic phenomena can sometimes be explained by subtler, stranger physics lurking in the background.

At the heart of our galaxy, something invisible may be holding everything together. Whether it is a black hole or a dark matter core, the answer will tell us not just what the Milky Way is made of, but how much we still have to learn about the universe we call home.

Study Details

V Crespi et al, The dynamics of S-stars and G-sources orbiting a supermassive compact object made of fermionic dark matter, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2026). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/staf1854