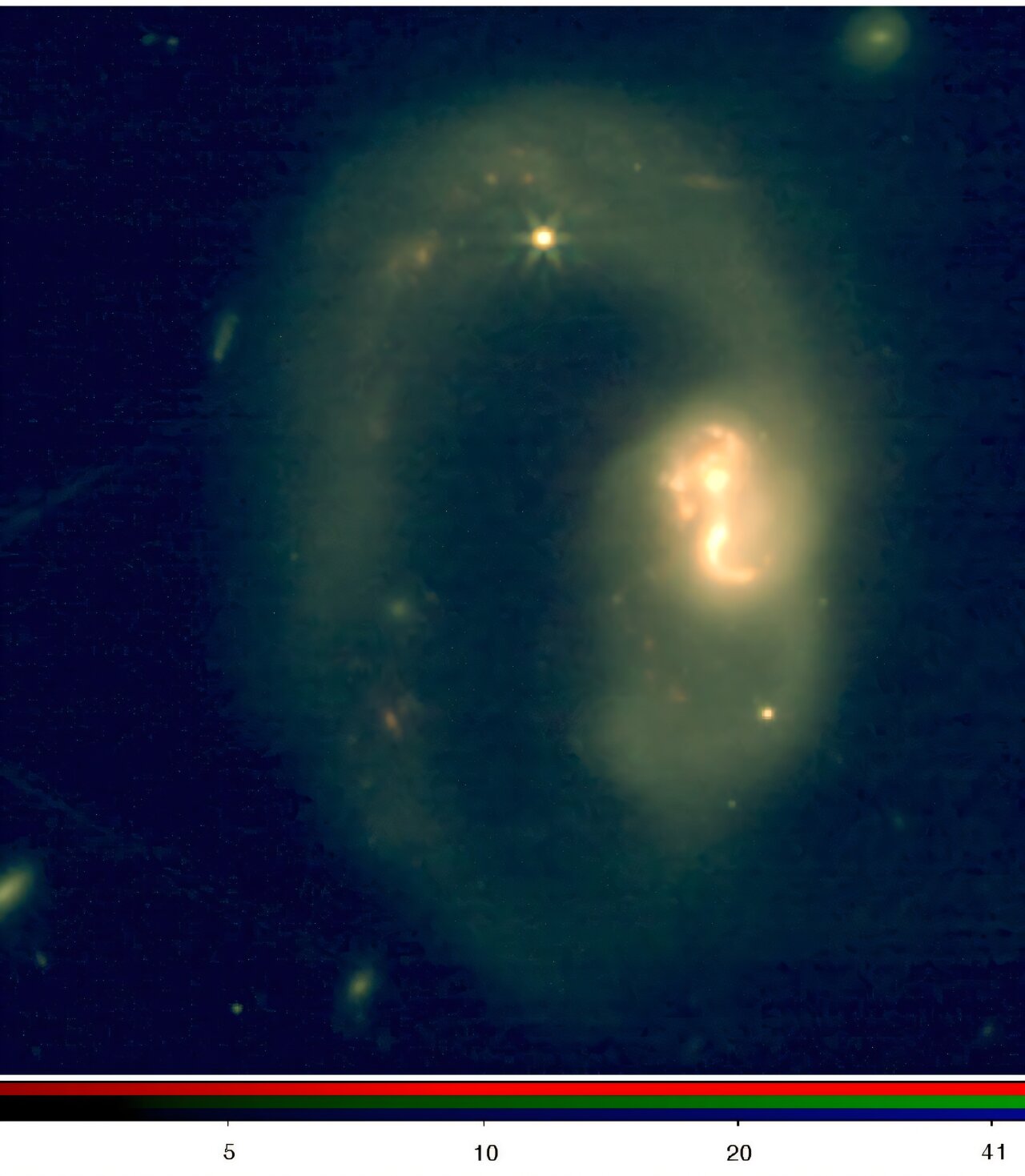

For decades, one nearby galaxy kept its heart hidden. Wrapped in thick veils of gas and dust, the nucleus of IRAS 07251–0248 absorbed almost all the light it produced, masking whatever fierce activity was happening inside. Conventional telescopes stared into the darkness and came away with little more than guesses. Somewhere behind that cosmic curtain sat a supermassive black hole, but beyond that, the chemistry of the region remained a mystery.

Then the James Webb Space Telescope arrived, carrying eyes tuned not to visible light, but to infrared wavelengths that can slip through dust like whispers through a closed door. When researchers finally looked again, they didn’t just glimpse the hidden nucleus. They discovered a chemical story far richer and stranger than anyone had imagined.

When Infrared Light Slips Through the Dust

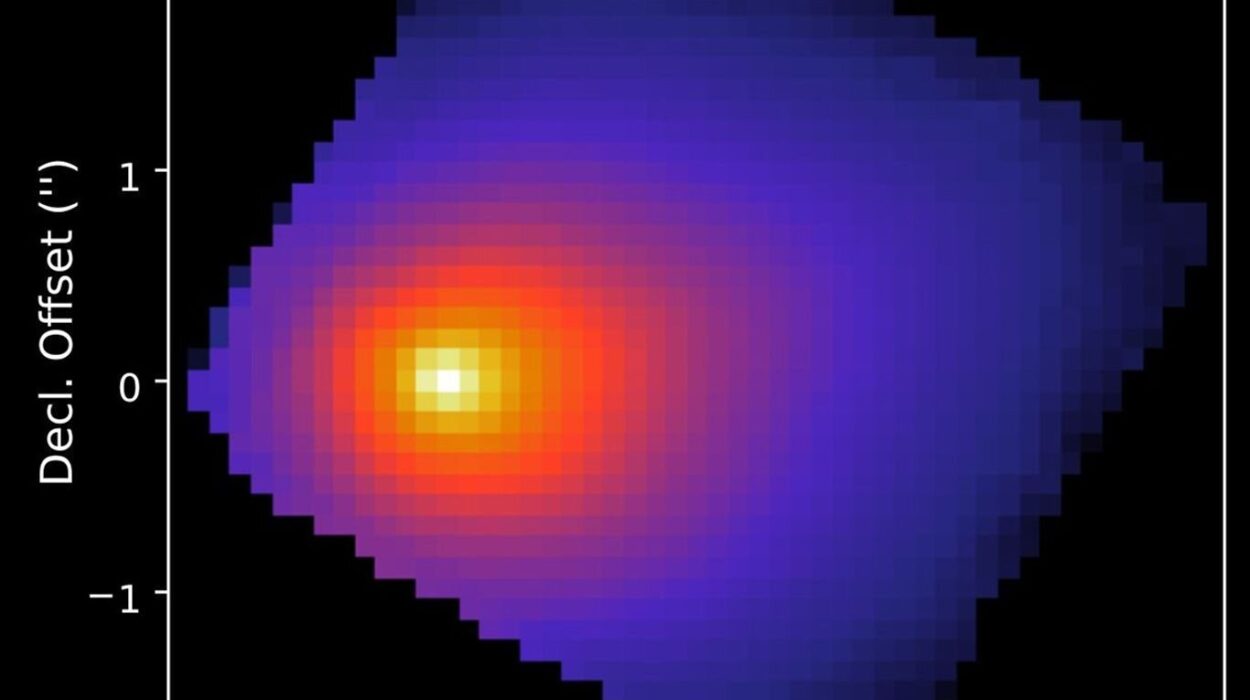

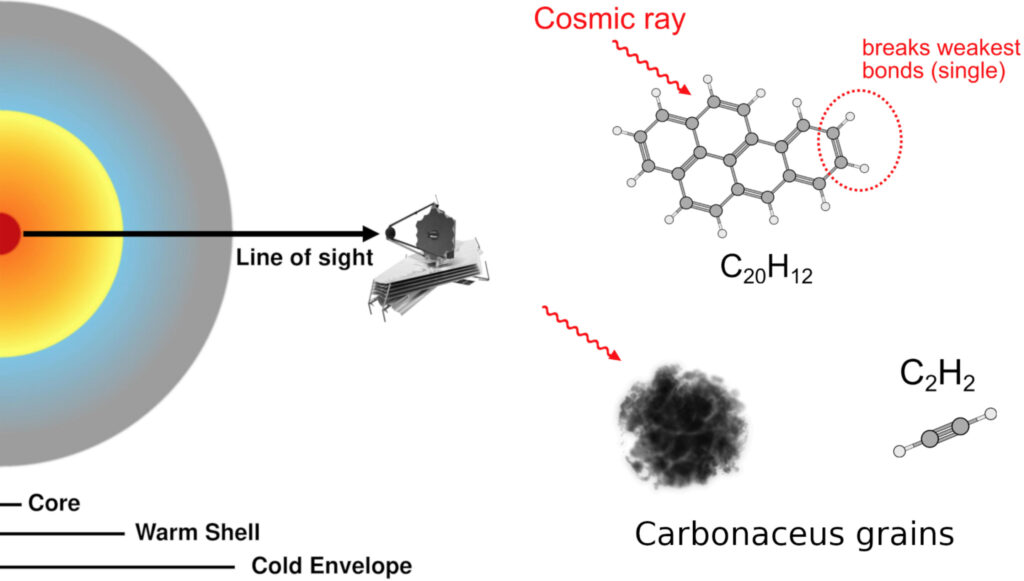

The breakthrough came from infrared observations, the kind that can penetrate thick clouds of obscuring material. Using JWST instruments NIRSpec and MIRI, scientists captured spectra spanning the 3–28 micron range, a window perfectly suited for detecting molecular fingerprints.

These spectra are more than pretty lines on a graph. Each dip and rise tells a story about molecules absorbing and emitting light, revealing what they are made of, how abundant they are, and even how warm they might be. In the buried nucleus of IRAS 07251–0248, those fingerprints piled up quickly, overlapping in ways that hinted at a crowded chemical environment.

The data allowed researchers to probe not only molecules floating freely as gas, but also material locked into ices and dust grains. For a region once thought nearly inaccessible, the nucleus suddenly felt chemically alive.

A Crowd of Molecules Where Few Were Expected

What emerged from the analysis surprised everyone involved. The nucleus contained an extraordinarily rich collection of small organic molecules, far more abundant than existing theories had predicted for such an extreme environment.

Among them were familiar hydrocarbons like methane (CH₄) and acetylene (C₂H₂), alongside more complex chains such as diacetylene (C₄H₂) and triacetylene (C₆H₂). The team also identified benzene (C₆H₆), a ring-shaped molecule that hints at even more intricate carbon chemistry.

Then came a first. For the first time outside our own galaxy, scientists detected the methyl radical (CH₃), a highly reactive fragment that rarely survives long without transforming into something else. Its presence suggested that active processes were constantly creating and replenishing these molecules.

Alongside the gas-phase chemistry, the nucleus was rich in solid material. Carbonaceous grains and water ices were found in large quantities, painting a picture of a dense, chemically layered environment where solids and gases interact continuously.

Carbon on Tap in a Hostile Place

The sheer abundance of these molecules raised an uncomfortable question. According to current models, such richness shouldn’t exist there. The nucleus is extreme, flooded with radiation and energetic particles, and buried under massive amounts of dust. So where was all this carbon chemistry coming from?

Lead author Dr. Ismael García Bernete described the finding as unexpected, noting that the observed molecular abundances were far higher than theoretical predictions. The implication was clear. Something in this environment was acting as a steady source of carbon, constantly feeding the chemical network.

Without that ongoing supply, the fragile molecules would quickly disappear. Instead, they thrived.

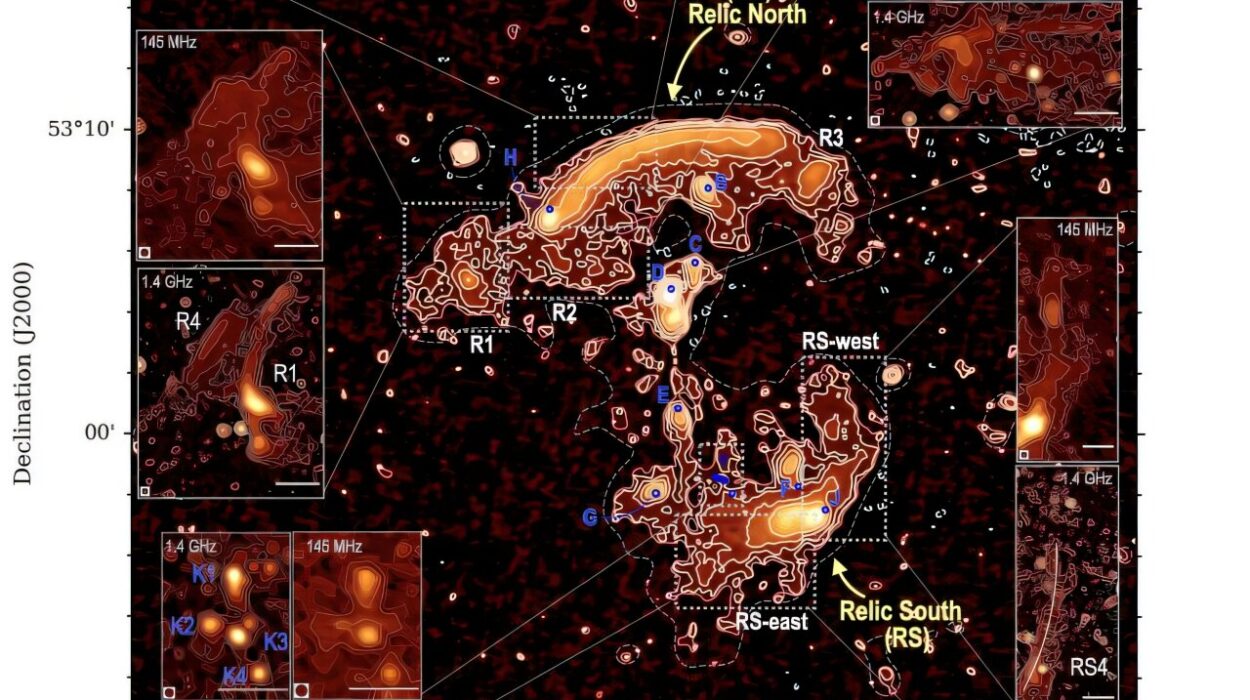

The Invisible Sculptors: Cosmic Rays

To understand the source of this chemical abundance, the team turned to advanced modeling techniques developed at the University of Oxford, including theoretical models of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs. These large, carbon-rich molecules are common in space and often survive in harsh environments by locking carbon into stable structures.

But the models revealed that heat alone couldn’t explain what JWST was seeing. Nor could turbulent gas motions. The chemistry pointed to another sculptor, one that operates silently and relentlessly: cosmic rays.

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles that permeate extreme galactic nuclei. In IRAS 07251–0248, they appear to collide with PAHs and carbon-rich dust grains, fragmenting them. Each impact breaks larger structures into smaller pieces, releasing small organic molecules directly into the gas.

This process doesn’t just create molecules once. It can continue as long as cosmic rays keep striking, providing a constant chemical supply line even in an otherwise hostile environment.

A Pattern Across Similar Galaxies

The story didn’t end with a single galaxy. When the researchers compared their results with data from similar systems, they found a clear pattern. The abundance of hydrocarbons correlated with the intensity of cosmic-ray ionization.

Where cosmic rays were more energetic or more numerous, small organic molecules were more abundant. This alignment strengthened the idea that cosmic rays are not just incidental players, but central architects of chemistry in deeply obscured galactic nuclei.

The findings suggest that such nuclei may act as factories of organic molecules, quietly shaping the chemical makeup of their host galaxies over time.

Small Molecules, Big Implications

None of the detected molecules are part of living cells. Yet their importance goes far beyond their size. As co-author Professor Dimitra Rigopoulou explains, small organic molecules can play a vital role in prebiotic chemistry. They represent stepping stones, the raw material from which more complex compounds like amino acids and nucleotides can eventually form.

In environments like the nucleus of IRAS 07251–0248, these building blocks are not rare accidents. They are products of ongoing, energetic processes that recycle carbon again and again.

This challenges the idea that extreme regions near supermassive black holes are chemically barren. Instead, they may be among the most active chemical workshops in the universe.

Peering Into Places Once Thought Unreachable

Beyond the chemistry itself, the study highlights the transformative power of JWST. Regions once hidden behind walls of dust are now open to detailed investigation. The telescope’s ability to capture both gas-phase molecules and solid materials in a single spectral sweep allows scientists to see how different components of the cosmic environment interact.

For the first time, deeply obscured galactic nuclei are no longer black boxes. They are dynamic systems with complex internal lives, shaped by radiation, particles, and the relentless recycling of matter.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research reshapes our understanding of where and how organic molecules form in the universe. It shows that even in the most extreme, dust-choked environments, chemistry does not merely survive. It flourishes.

By revealing a rich inventory of small organic molecules and identifying cosmic rays as key drivers of their formation, the study provides new insight into the chemical evolution of galaxies. It suggests that the ingredients for complex chemistry are being forged in places once dismissed as too violent or too hidden to matter.

Ultimately, this work opens new paths for exploring the origins of organic matter on cosmic scales. It reminds us that the universe is constantly experimenting, breaking and rebuilding carbon in countless ways. And sometimes, the most important stories are unfolding in the darkest places, waiting for the right light to finally bring them into view.

Study Details

JWST detection of abundant hydrocarbons in a buried nucleus with signs of grain and PAH processing, Nature Astronomy (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02750-0. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2602.04967