For decades, antibiotics have been medicine’s most dependable weapons. They turned once-fatal infections into routine treatments and gave doctors confidence that bacteria could be held in check. But while humans celebrated those victories, bacteria were quietly learning. They evolved, shared tricks, and adapted at a pace no drug pipeline could match. That slow, relentless learning curve has now erupted into a full-blown global emergency known as antibiotic resistance, or AR.

The danger is no longer theoretical. Resistant bacteria thrive in places where antibiotics are common and bacterial communities are dense. Hospitals, sewage treatment plants, animal farming operations, and fish farms have become training grounds where microbes learn how to survive chemical attacks meant to destroy them. As these resistant strains spread, the world is staring down projections of more than 10 million deaths per year by 2050 caused by infections that no longer respond to existing drugs.

In this tense landscape, scientists are searching for ways not just to slow resistance, but to undo it. At the University of California San Diego, a pair of research labs decided to try something radical. Instead of inventing new antibiotics, they asked a different question: what if bacteria could be persuaded to erase their own resistance?

Borrowing an Idea From Insects

The inspiration came from an unexpected place. In recent years, geneticists have developed tools known as gene drives, which spread specific genetic traits through insect populations. These systems have been explored as ways to disrupt harmful characteristics, such as the ability of mosquitoes to carry malaria parasites. The key idea is population engineering, introducing a genetic element that copies itself and spreads faster than normal inheritance would allow.

Professors Ethan Bier and Justin Meyer, working in the UC San Diego School of Biological Sciences, wondered whether this logic could be applied to bacteria. Instead of suppressing insect-borne disease, could a similar approach be used to target antibiotic resistance itself?

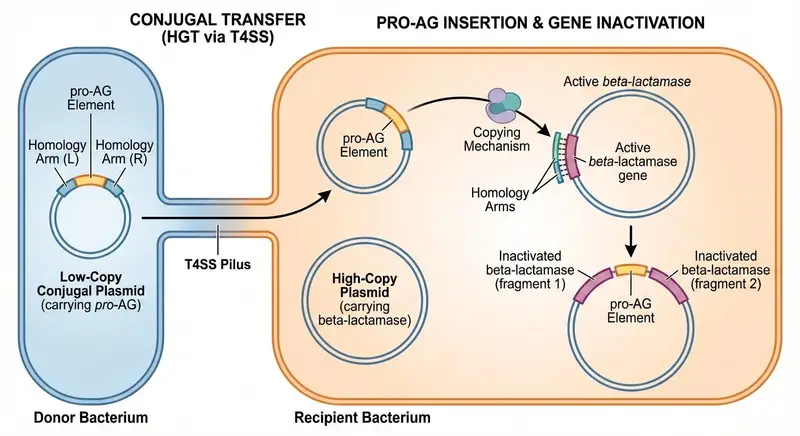

The result was a new CRISPR-based technology called Pro-Active Genetics, or Pro-AG. The goal was ambitious: to remove antibiotic-resistant elements from bacterial populations rather than merely containing them. This was not about killing bacteria outright. It was about disarming them.

“With this new CRISPR-based technology we can take a few cells and let them go to neutralize AR in a large target population,” Bier explained, capturing the bold simplicity of the idea.

The First Step Toward Disarming Resistance

The foundation for this work was laid in 2019, when Bier’s lab collaborated with Professor Victor Nizet from the UC San Diego School of Medicine. Together, they developed the initial Pro-AG concept. At its heart was a genetic cassette, a package of DNA designed to move from one bacterium to another.

This cassette targeted plasmids, the circular DNA molecules that bacteria use to carry and share antibiotic resistance genes. Plasmids are especially dangerous because they can move between different bacterial cells, spreading resistance rapidly across populations.

The Pro-AG cassette launched itself into these resistance genes and inactivated them. Once the resistance was disabled, bacteria that had previously shrugged off antibiotics became sensitive again. It was a powerful proof of concept, showing that resistance genes could be directly attacked and neutralized from within.

But the researchers knew they could go further.

When Bacteria Start Talking to Each Other

The next leap came with the development of a second-generation system known as pPro-MobV. This upgraded tool took advantage of a natural bacterial behavior called conjugal transfer, a process often described as bacterial mating. During conjugation, bacteria form a physical connection, a tiny tunnel through which DNA can pass from one cell to another.

Rather than relying solely on passive copying, pPro-MobV actively spread its CRISPR components through these mating tunnels. In essence, the bacteria themselves became the delivery system.

As described in the journal npj Antimicrobials and Resistance, the researchers showed that this approach worked even in one of the most stubborn bacterial environments imaginable: biofilms.

Biofilms are dense communities of microorganisms that cling to surfaces and shield themselves behind layers of protective cells. They contaminate medical equipment, industrial pipelines, and natural environments alike. Biofilms are notoriously resistant to cleaning efforts and antibiotic treatments, partly because their structure prevents drugs from penetrating effectively. They are also involved in the majority of infections that lead to serious disease.

Seeing pPro-MobV function inside biofilms was a critical breakthrough. It suggested that the technology could operate where antibiotics often fail.

Inside the Fortresses Where Antibiotics Struggle

Biofilms are not just scientific curiosities. They are one of the main reasons antibiotic resistance spreads so effectively. Within these microbial fortresses, bacteria exchange genetic material, including resistance genes, at high rates. The protective layers of the biofilm make it difficult for antibiotics to reach their targets, allowing resistant strains to survive and multiply.

“The biofilm context for combating antibiotic resistance is particularly important,” Bier said, noting that these growth forms are among the most challenging to overcome in clinical and enclosed environments such as aquafarm ponds and sewage treatment plants.

The implications stretch beyond hospitals. Roughly half of antibiotic resistance is estimated to come from the environment, where resistant bacteria circulate among animals, water systems, and human communities. If resistance could be reduced in these environmental reservoirs, the downstream effects on human health could be profound.

pPro-MobV’s ability to move through biofilms means it could, in principle, be used in health care settings, environmental remediation efforts, and even microbiome engineering, reshaping microbial communities rather than eradicating them.

Turning Bacteria’s Natural Enemies Into Allies

The researchers also discovered another intriguing delivery route. Components of the active genetic system could be carried by bacteriophage, or phage, viruses that naturally infect and compete with bacteria. Phage have long been seen as potential tools against bacterial infections, and they are already being specially engineered to evade bacterial defenses and insert disruptive genetic material into cells.

In this vision, pPro-MobV would not replace phage-based approaches but work alongside them. Engineered phage could deliver the CRISPR components into bacterial populations, where the Pro-AG system would then spread and disable resistance genes from within.

To address concerns about control and safety, the platform includes a built-in safeguard. It can incorporate homology-based deletion, a highly efficient process that allows the genetic cassette to be removed if desired. This means the system is not necessarily permanent and can be reversed under the right conditions.

Reversing the Flow of Evolution

Perhaps the most striking aspect of this research is its philosophical shift. Most strategies against antibiotic resistance focus on slowing its spread or managing its consequences. New drugs buy time. Infection control reduces exposure. Stewardship programs limit misuse. All are essential, but none truly reverse resistance once it takes hold.

“This technology is one of the few ways that I’m aware of that can actively reverse the spread of antibiotic-resistant genes,” said Meyer, who studies the evolutionary adaptations of bacteria and viruses.

By targeting the genes themselves and using bacterial social behaviors to propagate the fix, pPro-MobV turns evolution’s usual direction on its head. Instead of resistance traits spreading because they offer survival advantages, the system encourages the spread of sensitivity, restoring the effectiveness of existing antibiotics.

Why This Research Could Change the Story

Antibiotic resistance is often framed as an unstoppable force, a grim consequence of biology’s adaptability. The work at UC San Diego suggests a more hopeful narrative. By combining CRISPR, population engineering, and an intimate understanding of bacterial life, scientists are beginning to imagine ways to rewrite microbial rules from the inside.

The promise of pPro-MobV is not just in its technical elegance but in its scope. It operates in biofilms, travels through bacterial mating tunnels, collaborates with phage, and includes mechanisms for control. It addresses resistance where it forms and spreads, not only where it causes disease.

If approaches like this can be refined and safely deployed, they could help tip the balance in humanity’s favor, reducing the environmental and clinical reservoirs of resistance that threaten global health. In a world bracing for millions of deaths from untreatable infections, the idea that resistance itself might be undone offers something rare in the antibiotic era: a glimpse of reversal instead of retreat.

Study Details

Saluja Kaduwal et al, A conjugal gene drive-like system efficiently suppresses antibiotic resistance in a bacterial population, npj Antimicrobials and Resistance (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s44259-026-00181-z