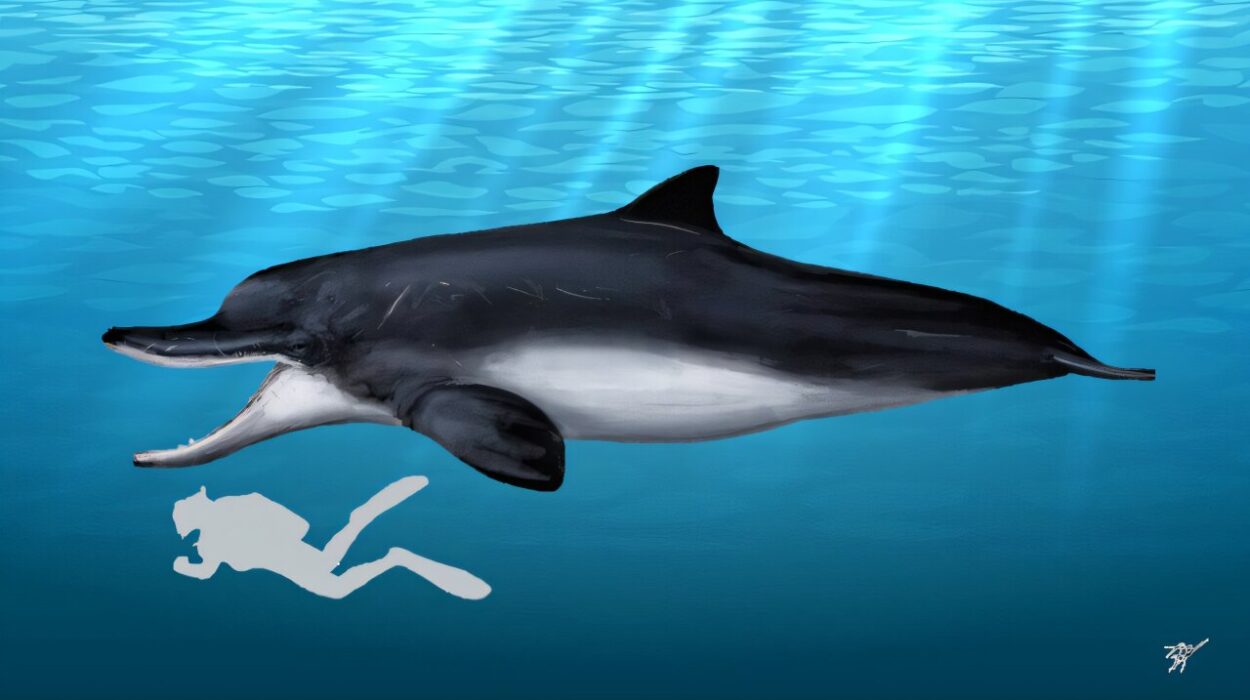

For centuries, the Andean condor has soared through the imagination of South America. With a wingspan that can stretch more than three meters, the bird appears almost mythical as it drifts across mountain skies, riding invisible rivers of wind. In the Andes, it has long been a symbol of power, protection, and spiritual transformation. Yet even legendary creatures carry stories that become lost to time. Now, a remarkable study led by Dr. Weronika Tomczyk has illuminated one of those forgotten chapters — one that reshapes our understanding of where the Andean condor once lived, thrived, and ultimately vanished.

The research team has provided the earliest empirical evidence that these majestic scavengers once inhabited the northern coastal regions of Peru, far beyond the high-altitude landscapes they occupy today. Their findings emerge from the Castillo de Huarmey archaeological site, a coastal ceremonial and administrative center of the Wari Empire, and offer profound implications for both science and conservation. Through a blend of zooarchaeology and isotopic chemistry, the study reveals a world in which condors soared over the Pacific coastline long before their retreat into the Andes.

A Bird of Myth, Majesty, and Urgency

The Andean condor is more than a bird; it is a cultural icon deeply embedded in the cosmology of pre-Columbian civilizations and modern Andean communities. Its image appears in textiles, ceramics, folklore, and festivals, its presence bridging earthly life with the heavens. Yet behind this cultural reverence lies a species under threat.

Today, the condor is classified as “Vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List. Habitat loss, lead poisoning from contaminated carcasses, poaching, and injuries linked to traditional celebrations such as the Rachi Condor and Yawar fiesta have all taken a toll on populations. Conservationists know that understanding a species’ historical range is crucial for protecting its future — but until recently, little concrete evidence existed to map the condor’s ancient presence along Peru’s northern coast.

This is where Dr. Tomczyk’s research steps in, offering new clarity to an old mystery.

An Ancient Mausoleum and a Hidden Story

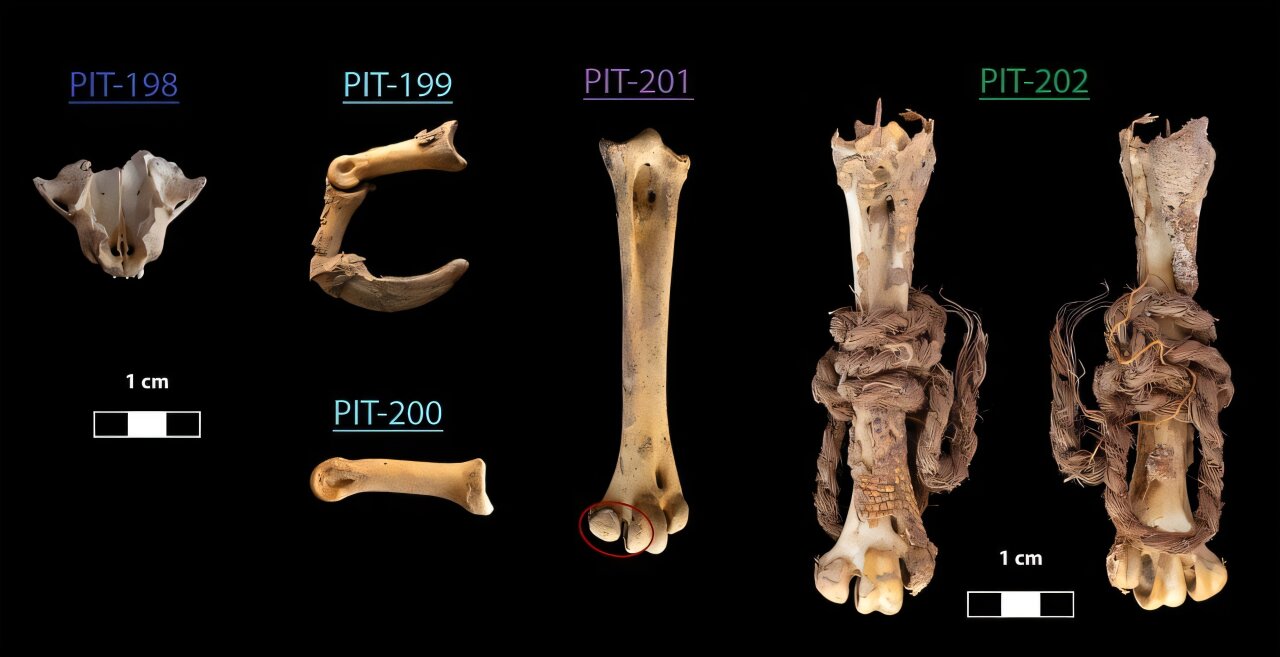

Castillo de Huarmey is a monumental archaeological complex on Peru’s Ancash coast, known for its lavish Wari-era mausoleums and elite burials. Within one of these structures — the “Red Mausoleum” — researchers uncovered 64 bones belonging to at least three Andean condors. These remains lay in small cellular rooms called recintos, deliberately placed yet remarkably untouched by human modification.

The zooarchaeological analysis revealed something unexpected: no cut marks, no signs of butchering, and no evidence of ceremonial dismemberment. The condors had been buried intact. Their presence in such a prestigious funerary context suggests that they were revered, valued, and perhaps symbolically integrated into Wari ritual practices. But where had they come from?

That question led researchers to the next phase: stable isotope analysis.

What the Bones Remember

Bones are not silent. They carry chemical signatures that record the landscapes an animal once inhabited, the food it consumed, and the waters it drank. Stable isotope analysis allows scientists to decode those signatures, transforming ancient remains into living testimonies.

For the condor bones from Huarmey, the team analyzed isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and strontium — elements that reveal diet, water sources, and geological origins.

The results were striking. All four tested bones showed isotopic signatures consistent with a marine-influenced diet. This strongly suggested that the condors had fed on coastal carrion, not inland terrestrial animals. They were birds of the coast, not visitors from distant mountain ranges.

One condor — identified as P-202 — showed a more mixed dietary signature. Two interpretations emerged. The first was behavioural: dominant condors often outcompete other scavengers, granting them access to a wider variety of food sources. A broad diet would therefore fit the life of a powerful, high-ranking bird. But there was another possibility. P-202 may have been held in captivity and fed terrestrial meat, likely camelid flesh — a staple protein for Wari communities. Supporting this idea was the discovery of a rope tied around the bird’s leg. Whether this rope symbolized ritual significance, domestication, or preparation for burial remains unknown, but its presence adds a haunting personal dimension to the story.

Both scenarios remind us that animals leave behind more than fossils — they leave behind traces of their relationships with humans.

Reimagining the Condor’s Ancient Range

This research provides the first direct archaeological evidence that the Andean condor once inhabited the northern Peruvian coast. Until now, historical records of their coastal presence were sparse, scattered, or speculative. The bones from Castillo de Huarmey anchor these ideas firmly in scientific fact.

Why did condors disappear from this part of Peru? Though the exact environmental triggers remain unclear, Dr. Tomczyk points toward patterns seen in Chile and Argentina, where condor populations retreated inland in response to intensified human activity. In Peru, rapid coastal urbanization likely disrupted the birds’ habitats and food sources. As settlements expanded and landscapes transformed, the condor’s ancient coastal world gradually faded away, leaving the highlands as their primary refuge.

Understanding this ecological history deepens our appreciation for the complex relationship between human development and wildlife survival.

More information: Weronika Tomczyk et al, Isotopic Evidence Reveals Marine Foodways and Captive Life Histories of Pre-Columbian Andean Condors, Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/15564894.2025.2559398