The word “prehistoric” often conjures images of colossal dinosaurs, ferocious predators, and vanished worlds frozen in stone. It suggests a deep past that has been sealed off from the present by extinction and time. Yet this image, while powerful, is incomplete. Prehistory did not vanish entirely. It persists—quietly, resiliently, and often unnoticed—within the modern world. Some animals alive today trace their lineage back tens or even hundreds of millions of years, surviving mass extinctions, continental drift, ice ages, and dramatic shifts in climate and ecology. They are not relics in the sense of being unchanged fossils; rather, they are living survivors, shaped by evolution but rooted in ancient ancestry.

These animals offer a rare and humbling perspective. They remind us that the present biosphere is not a fresh creation, but the latest chapter in an unbroken biological story. Every heartbeat, every scale, fin, or shell carries echoes of ancient seas, primeval forests, and long-lost ecosystems. Studying these creatures is not merely an exercise in curiosity. It is a way of understanding resilience, adaptation, and the deep continuity of life on Earth.

The following five animals are among the most remarkable survivors of deep time. Each one represents a lineage that emerged long before humans, before mammals dominated the land, and in some cases before dinosaurs even appeared. They are living bridges between worlds that no longer exist and the fragile, rapidly changing planet we inhabit today.

1. The Coelacanth: A Fish That Escaped Extinction

Few animals have reshaped scientific understanding as dramatically as the coelacanth. For much of the twentieth century, this fish existed only in the fossil record. Paleontologists believed that coelacanths had gone extinct approximately 66 million years ago, around the same time as the non-avian dinosaurs. Then, in 1938, a living coelacanth was hauled from the waters off the coast of South Africa, forcing science to confront the astonishing reality that a supposedly extinct lineage had been swimming unnoticed in the deep ocean.

Coelacanths belong to a group of lobe-finned fishes that first appeared more than 400 million years ago. Unlike most modern fish, which have thin, ray-supported fins, coelacanths possess fleshy, muscular fins supported by bone structures remarkably similar to the limbs of early tetrapods. These fins move in a coordinated, almost walking-like pattern, offering insight into the evolutionary transition from aquatic to terrestrial life.

From an anatomical perspective, the coelacanth is a mosaic of ancient traits. It has a hinged skull joint, allowing the front of the skull to lift during feeding—an unusual feature absent in most modern vertebrates. Its spine is not fully ossified but contains a fluid-filled rod called a notochord, a structure more commonly associated with primitive chordates. Even its heart shows characteristics intermediate between fish and early land vertebrates.

Despite its ancient lineage, the coelacanth is not a frozen artifact. Genetic studies reveal that it has continued to evolve, albeit slowly, adapting to a deep-sea lifestyle. Modern coelacanths inhabit steep underwater slopes at depths of several hundred meters, where temperatures are stable and light is scarce. This environment may have shielded them from the ecological pressures that drove many of their relatives to extinction.

Emotionally, the coelacanth stands as a symbol of humility in science. Its rediscovery reminded researchers that the fossil record, while invaluable, is incomplete, and that nature can still surprise us. The coelacanth is not merely a survivor; it is a messenger from a world that predates forests, flowering plants, and birds, offering a living glimpse into the deep evolutionary past.

2. The Horseshoe Crab: An Ancient Guardian of the Shore

Along the shallow coastal waters of several continents lives an animal that looks as though it has wandered out of a Paleozoic nightmare. With its domed shell, spiked tail, and compound eyes, the horseshoe crab appears alien and timeless. Yet this creature has endured for more than 450 million years, making it older than dinosaurs, older than reptiles, and even older than most fish lineages.

Despite its name, the horseshoe crab is not a true crab and not even a crustacean. It belongs to a group called chelicerates, which also includes spiders and scorpions. This evolutionary relationship is reflected in its anatomy. The horseshoe crab has book gills for respiration, multiple pairs of appendages adapted for feeding and movement, and a hard exoskeleton that must be shed during growth.

One of the most remarkable features of the horseshoe crab is its blood. Instead of hemoglobin, which uses iron to transport oxygen and gives human blood its red color, horseshoe crab blood contains hemocyanin, a copper-based molecule that turns blue when oxygenated. This blood is extraordinarily sensitive to bacterial toxins, a property that has made horseshoe crabs essential to modern medicine. Extracts from their blood are used to test the safety of vaccines, surgical implants, and intravenous drugs.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the success of the horseshoe crab lies in its simplicity and robustness. Its basic body plan emerged hundreds of millions of years ago and has proven remarkably effective. While minor changes have occurred, the overall structure has remained stable, a testament to the power of a well-adapted design.

Emotionally, the horseshoe crab evokes a sense of continuity that is both comforting and unsettling. When these animals crawl onto beaches to spawn, they enact a ritual older than vertebrate land animals. Their presence challenges the idea that progress in evolution always means complexity or novelty. Sometimes, survival comes from staying the course, weathering extinction events through resilience rather than reinvention.

3. The Crocodilian: A Living Dinosaur’s Contemporary

Crocodilians—crocodiles, alligators, caimans, and gharials—are often described as living dinosaurs, though this label is technically inaccurate. Dinosaurs and crocodilians share a common ancestor, but crocodilians belong to a separate lineage that has survived while non-avian dinosaurs did not. Nevertheless, crocodilians retain many traits that link them to the age of dinosaurs, making them among the most ancient large predators still alive today.

The crocodilian lineage dates back more than 200 million years. Early crocodile relatives occupied a wide range of ecological roles, from terrestrial runners to marine hunters. Modern crocodilians represent a narrower subset of this once-diverse group, but they retain key anatomical and physiological features that have contributed to their long-term success.

One such feature is their semi-aquatic lifestyle. Crocodilians are perfectly adapted to life at the boundary between water and land. Their eyes and nostrils sit atop the head, allowing them to breathe and observe while remaining mostly submerged. Their powerful tails provide propulsion in water, while their limbs enable movement on land.

Crocodilians also possess one of the most efficient bite forces measured in any living animal. Their conical teeth are designed not for chewing but for gripping and crushing prey. Combined with a slow metabolism and the ability to survive long periods without food, this makes them formidable and energy-efficient predators.

From a physiological perspective, crocodilians exhibit advanced traits that belie their ancient origins. They have a four-chambered heart, similar to birds and mammals, allowing efficient separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. This adaptation supports prolonged diving and bursts of intense activity.

Emotionally, crocodilians inspire a mix of fear and respect. Their presence feels primeval, as if time has thinned around them. To see a crocodile basking on a riverbank is to witness a form that once shared the world with towering sauropods and armored herbivores. Their survival underscores a sobering truth: evolution does not reward gentleness or beauty, but effectiveness within an ecological niche.

4. The Nautilus: A Living Spiral of Deep Time

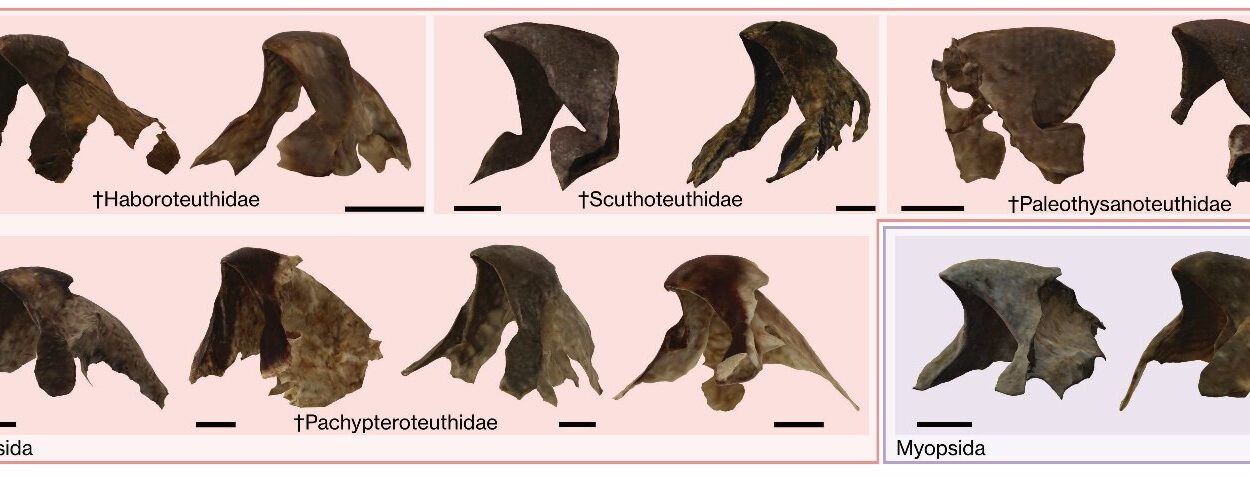

The nautilus drifts through the deep Indo-Pacific waters with a quiet elegance that seems untouched by urgency. Encased in a beautifully coiled shell divided into gas-filled chambers, it is a living reminder of a time when shelled cephalopods ruled the oceans. Nautiluses belong to a lineage that stretches back more than 500 million years, making them among the oldest surviving marine animals.

Unlike their more famous relatives—the octopus, squid, and cuttlefish—nautiluses retain an external shell. This shell is not merely protective; it is a sophisticated buoyancy device. By adjusting the gas and fluid content within its chambers, the nautilus can control its position in the water column with remarkable precision.

The nautilus’s anatomy is a blend of ancient and specialized features. It has dozens of small, adhesive tentacles rather than the suction-cup-lined arms of other cephalopods. Its eyes lack lenses, functioning more like pinhole cameras. These traits reflect an early stage in cephalopod evolution, preserved through time due to the nautilus’s stable ecological niche.

Nautiluses are slow-growing and long-lived, with lifespans that can exceed two decades. This slow pace of life contrasts sharply with the rapid life cycles of many modern marine animals. It also makes nautiluses particularly vulnerable to overexploitation, as their populations recover slowly from disturbance.

Emotionally, the nautilus embodies a sense of quiet persistence. Its spiral shell, often cited as an example of natural mathematical beauty, symbolizes continuity and balance. To encounter a nautilus is to witness an ancient design that has endured not through aggression or dominance, but through harmony with a stable environment. Its survival is a reminder that fragility and longevity are not mutually exclusive.

5. The Tuatara: A Reptile From a Lost World

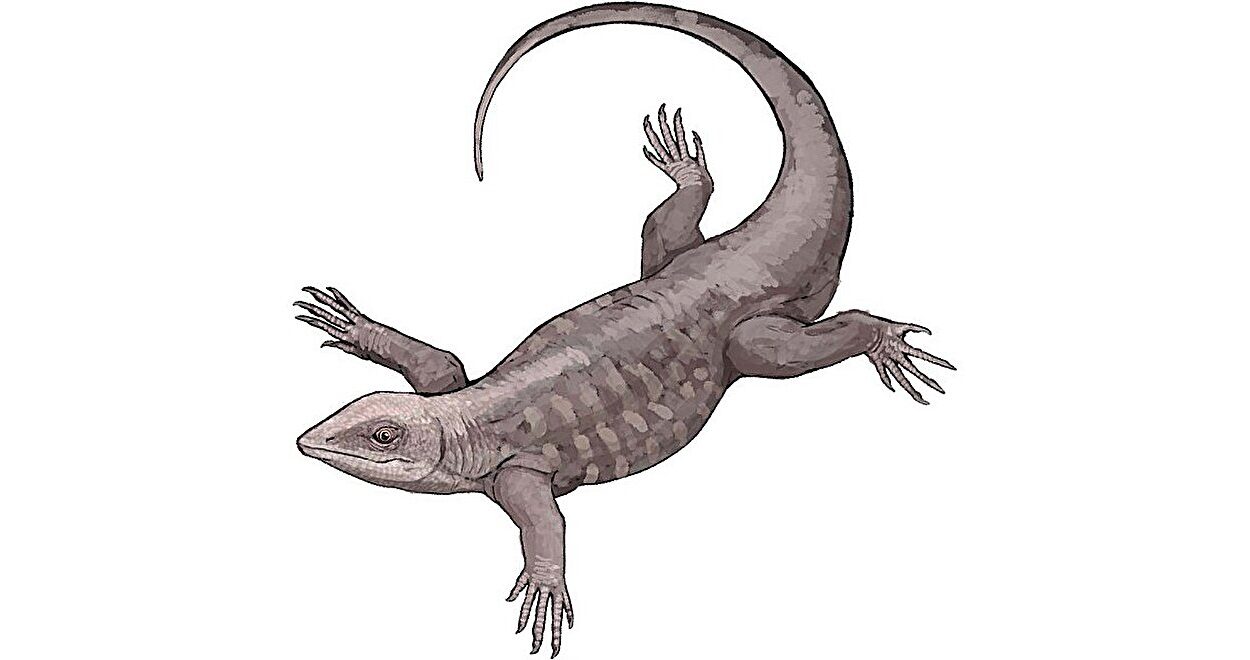

On a handful of islands off the coast of New Zealand lives an animal so ancient and distinctive that it defies easy classification. The tuatara resembles a lizard, but it is not a lizard. It is the sole surviving member of an entire reptilian order, the Rhynchocephalia, which flourished more than 200 million years ago and vanished everywhere else.

The tuatara’s anatomy reveals its deep evolutionary roots. It retains primitive features lost in other reptiles, including a unique skull structure and a “third eye,” known as the parietal eye, visible as a light-sensitive spot on the top of the head. While this eye does not form images, it plays a role in regulating circadian rhythms and seasonal behaviors.

Tuatara physiology is equally remarkable. They have one of the slowest growth rates and longest lifespans of any reptile, with some individuals believed to live more than a century. Their metabolism is adapted to cool temperatures, allowing them to remain active in conditions that would incapacitate most reptiles.

From an evolutionary perspective, the tuatara is invaluable. As the last representative of a once-diverse lineage, it provides insights into early reptile evolution and the traits that preceded the rise of dinosaurs and modern lizards. Its genome preserves genetic information that has been lost in other lineages, making it a living archive of reptilian history.

Emotionally, the tuatara evokes a sense of quiet reverence. It survives not through dominance, but through patience, longevity, and adaptation to a narrow ecological niche. In a world increasingly shaped by human activity, the tuatara’s continued existence feels precarious yet profound—a reminder of how much evolutionary history can hinge on a few fragile populations.

Conclusion: Living Echoes of Deep Time

These five animals are not evolutionary mistakes or outdated designs. They are survivors, shaped by natural selection to endure in environments that eliminated countless other forms of life. Their continued existence challenges simplistic narratives of progress and replacement, revealing evolution as a branching, unpredictable process in which survival depends on fit, not novelty.

Emotionally, these creatures connect us to a past far deeper than human memory. They remind us that Earth’s history is written not only in rocks and fossils, but in living bodies that still breathe, feed, and reproduce. To protect these animals is to protect chapters of a story that began long before our species appeared.

In an age of rapid environmental change, the survival of these prehistoric animals carries a warning as well as a wonder. If lineages that endured for hundreds of millions of years can be threatened within a few human generations, then responsibility becomes inseparable from knowledge. These living fossils are not just witnesses to Earth’s past—they are testaments to its fragility and to the extraordinary resilience of life itself.