Long before the spark of spoken language, before tools clinked against stone or fire warmed ancient caves, the story of the human brain began in silence. It did not erupt onto the scene, fully formed and powerful. It emerged slowly, sculpted over millions of years by the invisible hands of evolution. In the dim past, when our ancestors still moved on all fours and communicated with grunts, our brains were already changing—responding to the pressures of survival, reproduction, and adaptation.

To understand how the human brain—and with it, human intelligence—came to be, one must look not only at biology but at the harsh theatre of evolution itself. Here, intelligence was never an automatic reward; it was something earned in the fire of necessity.

The Primate Foundation

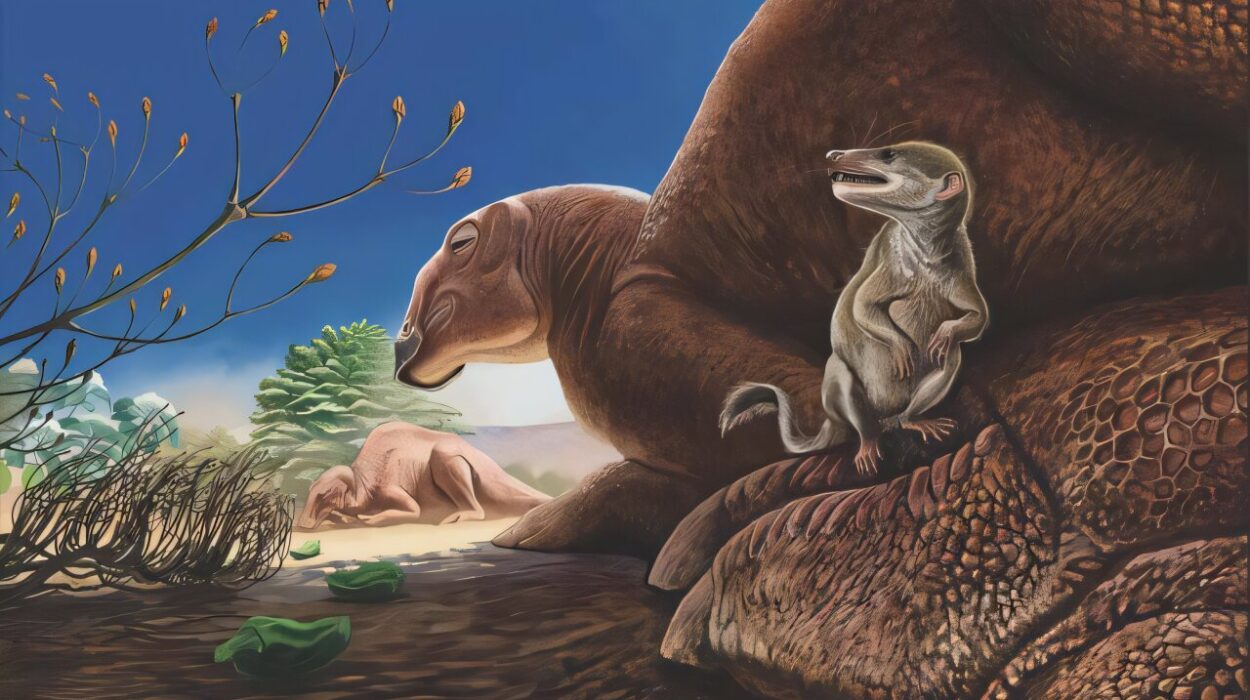

The roots of our cognitive story go back at least 60 million years, to the earliest primates. These small, tree-dwelling creatures relied heavily on vision rather than smell to navigate complex forest canopies. Evolution favored sharper eyes, better depth perception, and more accurate hand-eye coordination. As a result, the visual cortex—one of the most complex regions of the brain—grew disproportionately. Along with that came more advanced motor control, spatial awareness, and eventually, rudimentary social cognition.

Even at this early stage, social living played a critical role. Primates that could remember who groomed whom, who was dominant, who shared food, and who didn’t, had a survival edge. Evolution was beginning to reward not just strength, but memory, strategy, and emotional intelligence.

Walking Upright, Thinking Differently

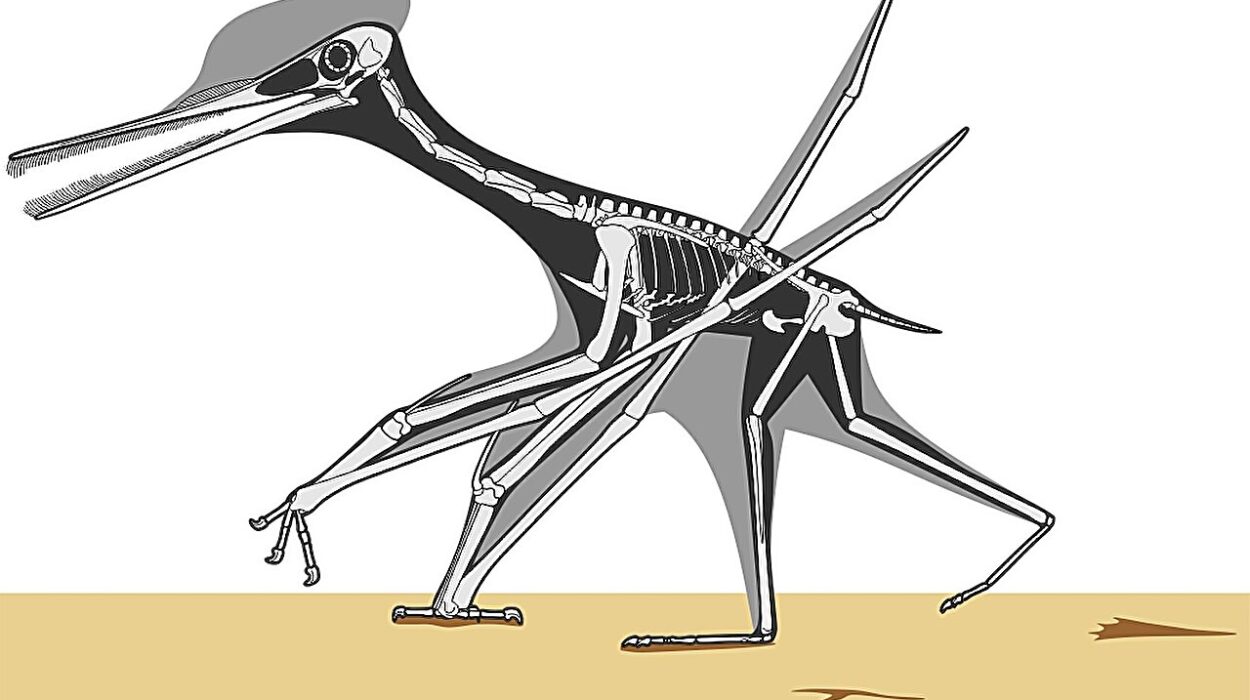

About 6 to 7 million years ago, a fork appeared in the evolutionary road. One lineage of apes began walking on two legs. Bipedalism was a radical adaptation, one that freed the hands for tool use and altered the structure of the pelvis and spine. But this change also started a subtle reshaping of the skull. The angle of the foramen magnum—the hole at the base of the skull through which the spinal cord passes—shifted to accommodate upright posture. These changes indirectly influenced brain orientation and growth patterns.

With hands liberated, early hominins could manipulate objects in more complex ways. Tool use, in turn, created new evolutionary pressures for finer motor skills, improved problem-solving, and more advanced learning mechanisms. Intelligence, once an auxiliary trait, became central to survival.

The Fire Within

Perhaps one of the most transformative events in human evolution was the harnessing of fire. While the exact date remains debated, evidence suggests that Homo erectus, nearly 1.5 million years ago, had control of fire. This wasn’t just about warmth or protection from predators—it changed everything about how the brain could grow.

Fire meant cooking. And cooking unlocked calories.

Raw food demands more energy to digest, and provides fewer nutrients. Cooked food, by contrast, is easier to chew, easier to digest, and releases more usable energy. This surplus energy could now be redirected to support the most metabolically expensive organ in the body: the brain.

The human brain today consumes about 20% of the body’s energy at rest, despite accounting for only about 2% of body weight. Such an energy hog could not have evolved without a corresponding increase in caloric intake—and cooking made that possible.

With more energy available, brain size began to increase. And with increased brain size came more sophisticated behaviors, from coordinated hunting strategies to early forms of language.

The Social Brain Hypothesis

One of the most compelling explanations for why the human brain grew so large lies in the nature of our relationships. According to the social brain hypothesis, the primary driver of human intelligence wasn’t abstract problem-solving or hunting prowess—it was navigating complex social lives.

Living in groups comes with advantages: protection, cooperation, shared knowledge. But it also introduces new cognitive challenges. To survive socially, individuals had to understand subtle hierarchies, remember allies and enemies, detect deception, and forge bonds through empathy and trust.

The neocortex—the part of the brain associated with higher cognitive functions—expanded not because we needed to invent tools, but because we needed to manage the social demands of living in ever-larger groups. Gossip, for instance, became a tool as vital as the spear. Being able to track who did what to whom, who owed favors, who cheated—this kind of mental bookkeeping was evolutionary gold.

In this framework, intelligence is not just about solving puzzles—it’s about understanding people.

The Rise of Language

At some point between 200,000 and 50,000 years ago, something extraordinary happened. Our ancestors began to use fully syntactical language. Not just grunts or gestures, but structured sentences, with grammar, tenses, metaphors, and nuance. Language exploded human cognition.

Suddenly, knowledge could be passed from one generation to the next not just through imitation but through precise instruction. Culture, once ephemeral, became enduring. Myths, rituals, laws, and histories could be told, retold, and refined.

The brain responded accordingly. Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area—regions associated with language production and comprehension—became more specialized. Neural networks evolved to handle symbolic thought and narrative structure. Communication ceased to be reactive; it became creative, strategic, and poetic.

Language also transformed thought itself. We no longer had to think in images or actions alone—we could think in words, in abstractions. The inner voice was born.

Toolmaking and Mental Time Travel

Humans are the only animals known to make tools to make other tools. This recursive thinking—planning multiple steps ahead—requires a brain capable of simulating possible futures. In neuroscience, this is called “mental time travel”: the ability to project oneself forward in time, imagine scenarios, and make decisions based on hypotheticals.

This capacity for foresight is deeply tied to the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain responsible for executive functions like planning, impulse control, and working memory. Its enlargement in humans is no accident. Evolution had begun selecting for creatures who could imagine a trap before setting it, who could remember a drought from a decade ago and prepare for the next one.

Toolmaking wasn’t just about smashing rocks together—it was an externalization of thought. Every tool carried within it the memory of a plan, a purpose. As tools evolved, so too did the cognitive machinery that created them.

Neoteny and the Child Brain

One of the most bizarre twists in our evolutionary tale is the retention of juvenile traits into adulthood—a phenomenon known as neoteny. Compared to other primates, humans are born prematurely. Our brains are underdeveloped at birth, forcing infants to rely completely on caregivers. But this biological handicap came with an extraordinary advantage: plasticity.

A human child’s brain is more adaptable, more capable of forming complex neural connections, than almost any other species on Earth. Because so much of brain development happens after birth, experience plays a massive role in shaping intelligence. Language acquisition, cultural learning, emotional attachment—all these critical aspects of human life are built on the foundation of a highly malleable brain.

Evolution favored those who could learn rapidly, who could adapt not just genetically but culturally. This dynamic gave rise to a new form of evolution: not through genes alone, but through ideas, traditions, and shared wisdom. In a sense, our intelligence became transgenerational.

Emotion and Empathy: Intelligence with a Heartbeat

It’s tempting to think of intelligence as cold, robotic, and logical. But the human brain did not evolve in a vacuum of reason. It evolved in the cradle of emotion.

Emotions are not irrational outbursts—they are evolutionary signals. Fear kept our ancestors alive. Love bonded parents to vulnerable infants. Shame regulated social behavior. Joy reinforced actions that benefited the tribe.

The limbic system, especially the amygdala, hippocampus, and anterior cingulate cortex, plays a crucial role in emotional regulation. These structures are ancient, but in humans they interact with the higher-order parts of the brain to create complex emotional states. Empathy, in particular, may have been one of the most important catalysts of human intelligence. Being able to imagine what others feel is the beginning of compassion, morality, and even art.

Mirror neurons—cells that fire both when we perform an action and when we see someone else do it—may be the neurological basis for this shared experience. They blur the boundary between self and other. They allow us to learn by watching, to feel another’s pain as our own.

In evolutionary terms, a species that could cooperate more deeply, bond more strongly, and sacrifice for the group stood a better chance of survival.

The Cognitive Explosion and Cultural Evolution

Roughly 50,000 years ago, a “cognitive revolution” swept across Homo sapiens. Artifacts from this period—ornaments, burial rituals, musical instruments—point to an explosion of creativity and symbolic thinking. Humans began to craft not just tools, but stories, religions, and identities.

What caused this leap remains a subject of debate. Some suggest a genetic mutation triggered it. Others argue it was the accumulation of cultural knowledge reaching a tipping point. Either way, the human brain didn’t just solve problems—it began inventing meaning.

This shift had a profound feedback effect. Cultural innovation created new environments, which in turn selected for brains that could navigate them. Evolution and culture became intertwined, each feeding the other in a spiral of complexity.

The High Cost of Intelligence

Yet our intelligence came at a price. The human brain, for all its power, is fragile. It requires an extended childhood, high parental investment, and enormous energy. It is prone to disorders, from schizophrenia to Alzheimer’s. Its very plasticity makes it vulnerable to trauma and environmental stress.

Moreover, our brains evolved for a world of small tribes, immediate dangers, and face-to-face interactions. In modern civilization—with its digital overload, sedentary lifestyles, and artificial social structures—our ancient brains are often overwhelmed. We are running Paleolithic hardware on a modern operating system.

Still, the fact that we can reflect on this mismatch, that we can use science to understand our limitations, is itself a testament to the power of the evolved brain.

The Unfinished Brain

Despite our towering achievements—from landing on the Moon to mapping the genome—the human brain remains a work in progress. Evolution doesn’t produce perfection. It produces “good enough.” Our intelligence is not an end-point, but a stepping stone. Natural selection continues to operate, and the pressures we face today—climate change, technological disruption, global interconnectedness—may be shaping our descendants in ways we can scarcely imagine.

Some scientists speculate that human intelligence might one day merge with machines. Others fear a decline in critical thinking amid algorithmic manipulation. Regardless of the path, one thing is clear: the evolution of the human brain is not over.

It is ongoing, and we are its architects.

A Universe Inside Our Heads

In the grand tapestry of life, the human brain is one of evolution’s most astonishing experiments. It can contemplate black holes, compose symphonies, build civilizations, and imagine gods. It can grieve, love, deceive, and forgive. It is not just an organ—it is a universe of meaning and memory, shaped by millions of years of trial, error, and imagination.

As we continue to unlock its secrets, we are also unlocking the story of ourselves—not just where we came from, but where we’re going.

Because the greatest story evolution ever told may be the one we are still writing, neuron by neuron, thought by thought, in the silent, brilliant theater of the mind.