For more than a decade, the Higgs boson has stood at the center of one of physics’ greatest stories. First glimpsed in 2012 at the Large Hadron Collider, the elusive particle arrived not with fireworks but with a quiet confirmation of a theory that had hovered for decades. Since that moment, physicists have been listening closely for new hints about how the Higgs behaves, waiting for any clue that reveals what it truly means to give mass to the particles that make up our world.

Now, researchers at CERN say they have heard a new whisper. By combining the two most recent runs of the ATLAS detector, they have gathered evidence that the Higgs boson can decay into a muon and an antimuon—a delicate transformation that has never before reached this level of statistical clarity. It is a step toward understanding whether the Higgs speaks to lighter particles with the same voice it uses for heavier ones, or whether there are surprises waiting inside its faint signals.

The Quest for a Rare Disappearance

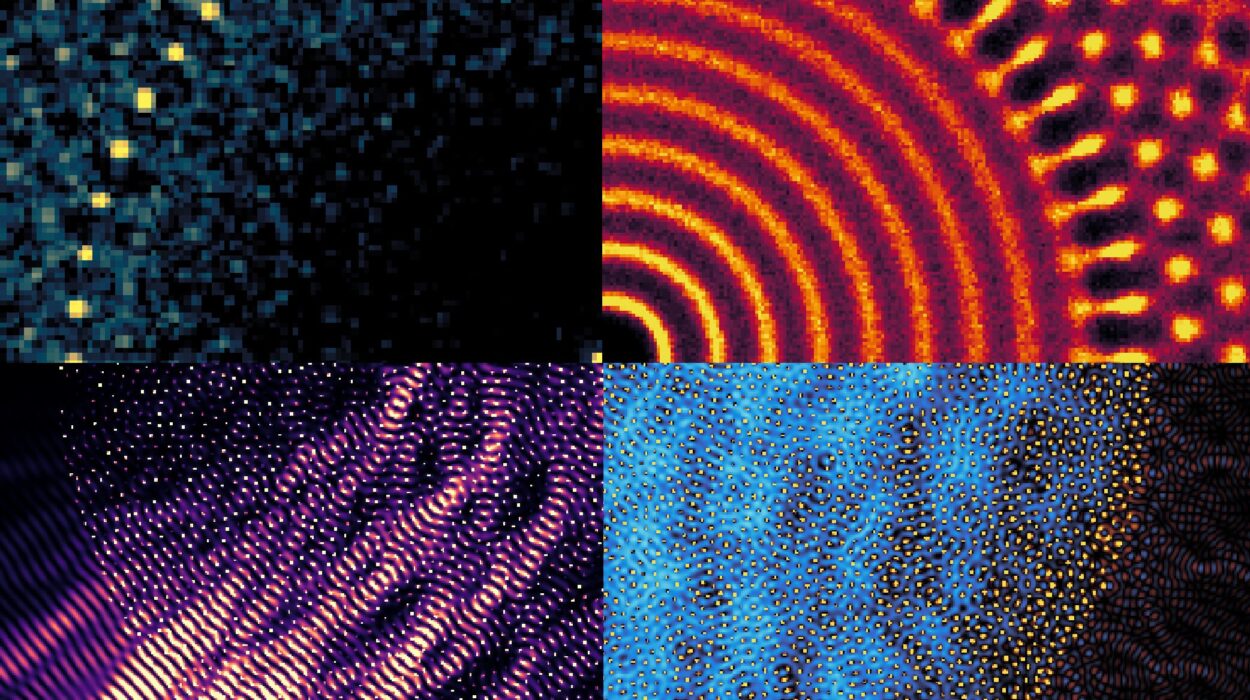

The new study, published in Physical Review Letters, reports something physicists call a significance of 3.4 standard deviations. Translated out of scientific shorthand, that means the signal rises 3.4 times above the noise of ordinary background events. In the world of high-energy physics, that is strong enough to be called evidence but not yet certain enough to claim a discovery. Still, it edges past the previous benchmark of 3.0 standard deviations reported by the CMS detector, giving ATLAS the sharpest view so far of this rare decay.

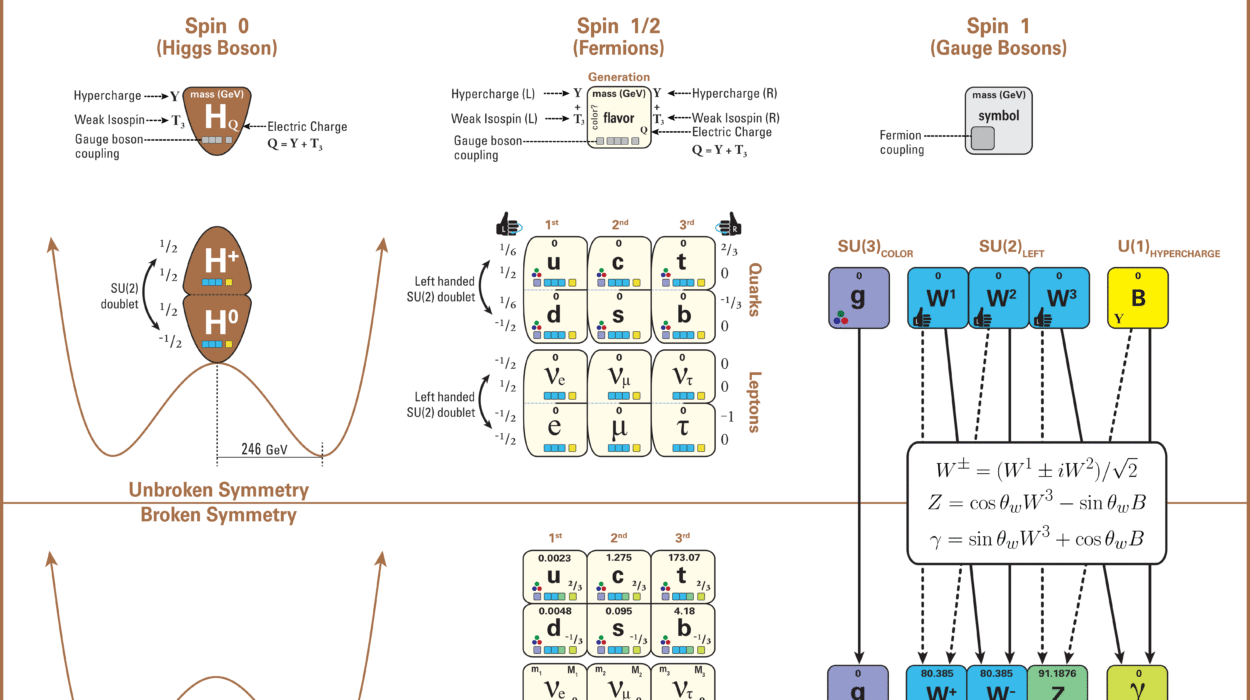

The decay itself is astonishingly improbable. A Higgs boson typically vanishes into heavier third-generation fermions—top quarks, bottom quarks, and tau leptons—because the Higgs interacts more strongly with particles of greater mass. These interactions, known as Yukawa couplings, are where the story of mass begins. As the study authors put it, “The Yukawa interactions of the Higgs boson to third-generation charged fermions have been firmly established. However, its Yukawa coupling to second-generation fermions has yet to be conclusively determined.”

That challenge is what makes the Higgs-to-muon decay such an important target. Muons belong to the second generation of matter, heavier than electrons but far lighter than the particles whose Higgs interactions have already been confirmed. If the Higgs is observed decaying into muon–antimuon pairs at just the right rate, it would strengthen the idea that the Higgs mechanism works seamlessly across generations. If not, it could hint at cracks in the Standard Model.

So far, the evidence from ATLAS suggests the Higgs is behaving exactly as expected.

Following the Higgs Into the Heart of Mass

To understand why this decay matters, it helps to revisit the strange architecture of the particle world. According to the Standard Model, particles are not simply given mass the way objects are assigned weight. Instead, mass arises through interactions with the Higgs field, a kind of invisible ocean that fills all of space. The Higgs boson is the brief visible ripple on this field, born in high-energy collisions and gone almost instantly.

When a particle interacts with the Higgs field, its motion is resisted. This resistance is what we interpret as mass. Heavier particles interact strongly; lighter particles interact weakly; massless particles do not interact at all. The fact that the strength of these interactions is proportional to mass is a remarkable built-in orderliness, a matching of mathematical expectation and physical reality.

But that order has only been firmly confirmed for the heaviest particles, the ones easiest to detect in high-energy collisions. The muon, as a second-generation fermion, lies halfway down the ladder. Its interactions with the Higgs are much quieter. Detecting a Higgs boson decaying into a muon and an antimuon is like hearing a soft footstep in a roaring stadium.

That is why combining the latest two runs of ATLAS was crucial. The proton-proton collisions produced at the LHC are chaotic events—subatomic wreckage exploding into dozens of particles at once. Finding a pair of muons among that chaos is already challenging. Finding them in a pattern that points back to a fleeting Higgs decay is even harder. Yet when the data from both runs are woven together, a signal emerges. It is faint, but it is unmistakably there.

A Glimpse Toward Tomorrow’s Higgs

The researchers emphasize that the new results are “compatible with the Standard Model expectations,” meaning nothing strange or unexpected has appeared—yet. But compatibility is not a dead end. It is a foundation. The fact that ATLAS sees evidence for this decay at 3.4 standard deviations means future runs could push that number even higher, crossing the threshold into a full discovery.

If that happens, it will deepen the case that the Higgs interacts with second-generation fermions just as the Standard Model predicts. And if that pattern holds, it opens the possibility of chasing even lighter particles. The study notes that “additional runs at ATLAS, as well as CMS, may further increase confidence in these results and even open the door to probing Higgs couplings for even lighter particles.” That means the ultimate prize could be the Higgs interaction with electrons, the first-generation cousins of muons.

Such a measurement lies far beyond today’s reach. But so did the Higgs boson itself, once.

Why This Discovery Matters

Every new piece of data about the Higgs boson does more than refine a theory. It sharpens our understanding of what mass is and how the universe is built. The Higgs is not just another particle. It is the keystone of the Standard Model. If it behaves exactly as predicted, that strengthens one of the most successful scientific frameworks ever constructed. If it deviates even slightly, it could open the door to new physics, new particles, or new forces.

This study does not overturn the Standard Model. It strengthens it. Yet it also pushes open the gate to a longer journey, one where the Higgs may reveal more about how matter is organized across generations. The signal detected by ATLAS is a hint, a promise, and perhaps a preview of discoveries still ahead. In listening closely to this rare decay, physicists are learning how the Higgs speaks—and what it might be trying to tell us about the deepest workings of the universe.

More information: G. Aad et al, Evidence for the Dimuon Decay of the Higgs Boson in 𝑝𝑝 Collisions with the ATLAS Detector, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/gzdh-p159