Nearly a century ago, Albert Einstein sketched an experiment in his mind with the quiet confidence of someone certain he had found a crack in the foundations of quantum mechanics. It was not a laboratory proposal in the usual sense. It was a challenge, a carefully reasoned scenario meant to expose what Einstein believed was a deep inconsistency in the way the quantum world was being described. For decades, the experiment lived only on paper and in debate halls, a symbol of one of science’s most famous intellectual rivalries. Now, scientists in China have finally carried it into the laboratory, and the result has echoed a verdict that history has delivered many times before.

The experiment was first imagined when Einstein sought to disprove the quantum mechanical principle of complementarity, put forward by Niels Bohr and his school of physicists. Complementarity claims that certain properties of particles cannot be measured at the same time. According to this view, nature draws a hard line between what can be known together and what must remain mutually exclusive. Einstein never accepted this boundary quietly. The new result, reported by Jian-Wei Pan of the University of Science and Technology of China and colleagues in Physical Review Letters, once again supports the Copenhagen school’s interpretation of quantum mechanics. At the same time, it opens a window onto deeper questions that still linger at the heart of the theory.

When Giants Argued Over Reality

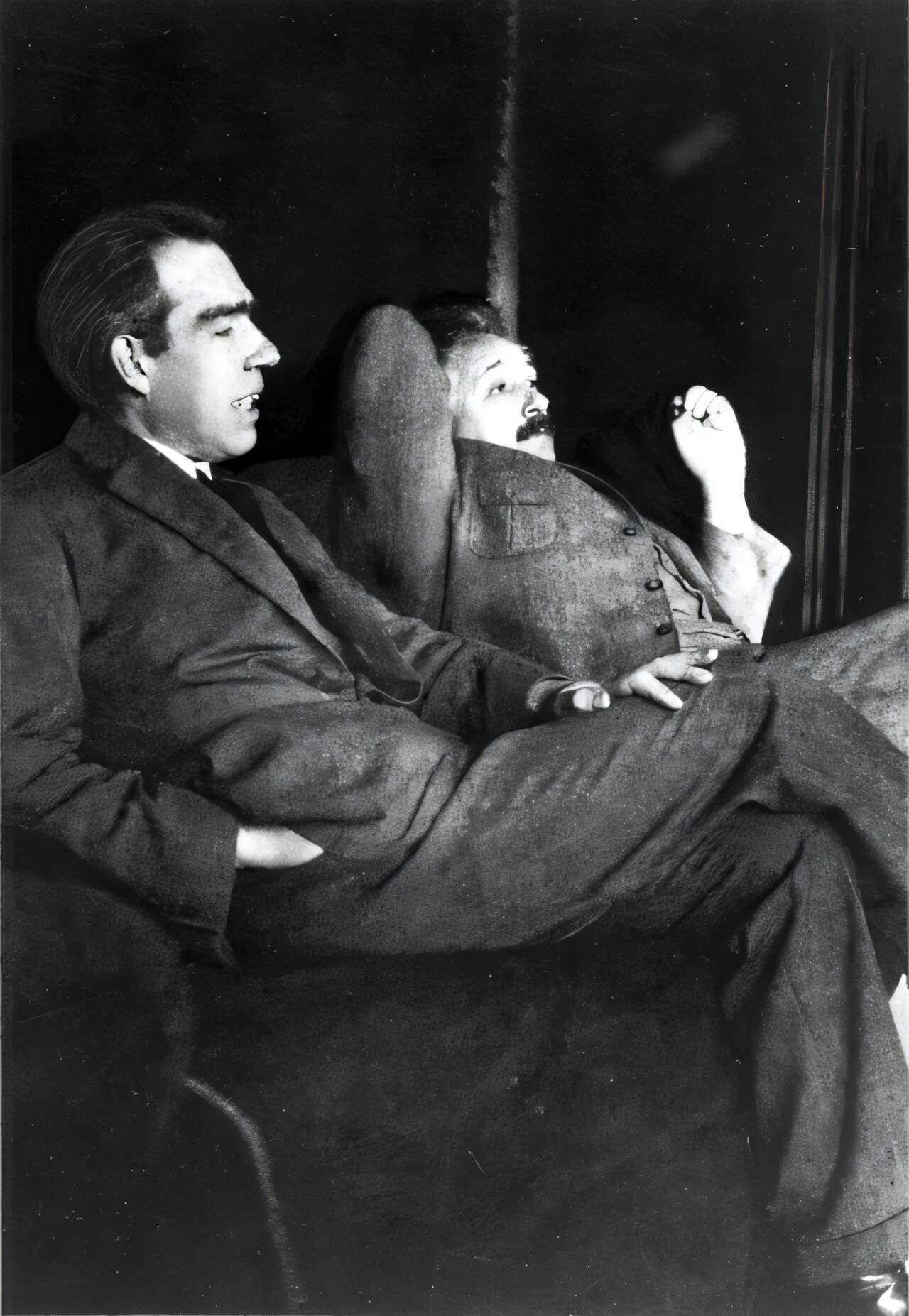

When Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr crossed paths at physics conferences, their conversations often turned into friendly but relentless sparring matches over the meaning of quantum mechanics. Einstein, skeptical of the standard picture that was taking shape in the 1920s, delighted in proposing scenarios that he believed exposed its flaws. Bohr, equally committed to his interpretation, was always ready to respond.

Their most famous exchange unfolded at the 1927 Solvay conference in Brussels. There, amid a gathering of the era’s greatest physicists, Einstein voiced his discomfort with quantum randomness by declaring, “God does not play dice with the universe.” His objection was not merely philosophical. He believed that quantum mechanics, as Bohr understood it, failed to give a complete and consistent account of physical reality.

Central to their disagreement was the principle of complementarity. Bohr argued that quantum particles possess pairs of properties that cannot be simultaneously measured, such as position and momentum, or frequency and lifetime. This idea lies beneath the concepts of wave-particle duality and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Einstein thought he could devise an experiment that would reveal both sides of a particle’s nature at once, exposing a contradiction at the heart of complementarity.

The Slits That Split More Than Light

Einstein’s proposal built upon a classic demonstration of quantum strangeness: the double-slit experiment. In its standard form, particles are aimed at two narrow, horizontally aligned slits. On a screen behind them, an interference pattern appears, a series of fringes that reveal the wave-like nature of the particles. This behavior was first described for light by Thomas Young in 1801 and later demonstrated for electrons in 1927.

Einstein imagined adding a twist. Before the particles reached the double slits, they would pass through a single, horizontally aligned slit mounted on momentum-sensitive springs at the top and bottom. If a particle were destined for the upper of the two later slits, it would impart a downward momentum to the single slit as it recoiled. Measuring this recoil, Einstein argued, would reveal which path the particle took, showcasing its particle-like nature.

Yet after passing through the double slits, the same particles would still produce an interference pattern on the screen, displaying their wave-like nature. If both outcomes could be observed together, Einstein claimed, the principle of complementarity would be violated. Bohr, however, was unconvinced. He argued that the very act of precisely measuring the momentum of the slit would, through the uncertainty principle, introduce a large uncertainty in the particle’s position. The result would be a blurring of the interference fringes, preserving complementarity after all.

For decades, this argument remained a theoretical duel. The experiment was too delicate to perform, its demands far beyond the reach of available technology. That has now changed.

A Single Atom Takes the Stage

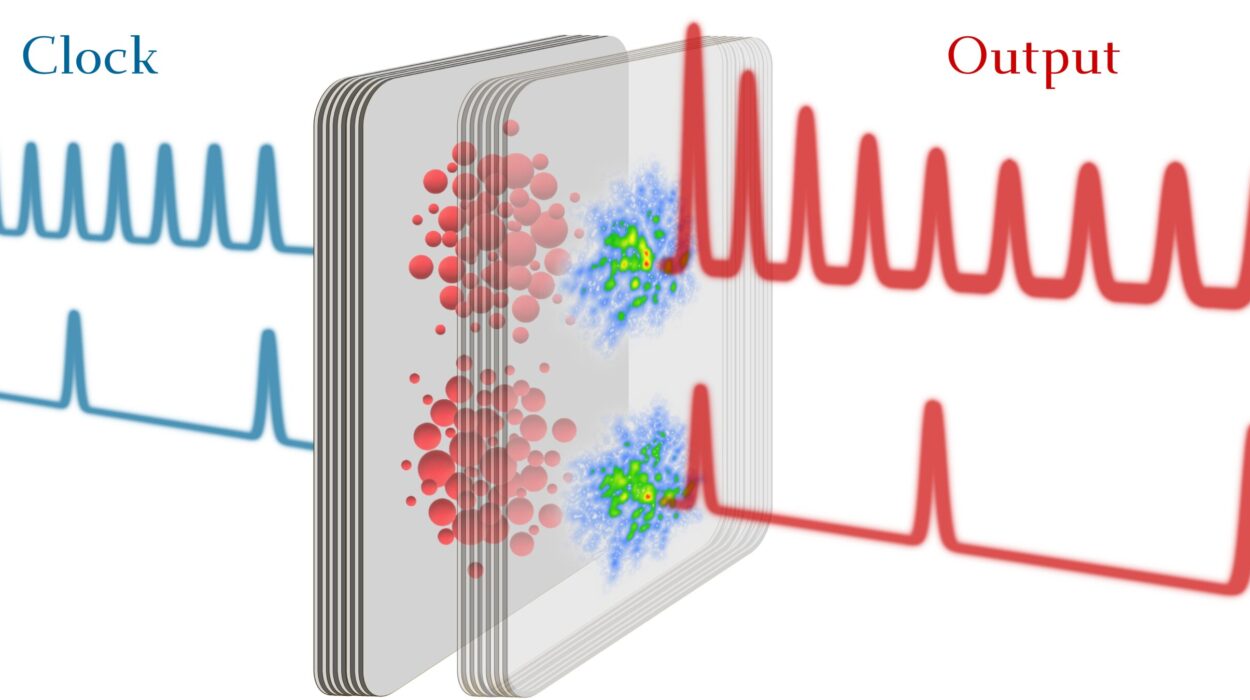

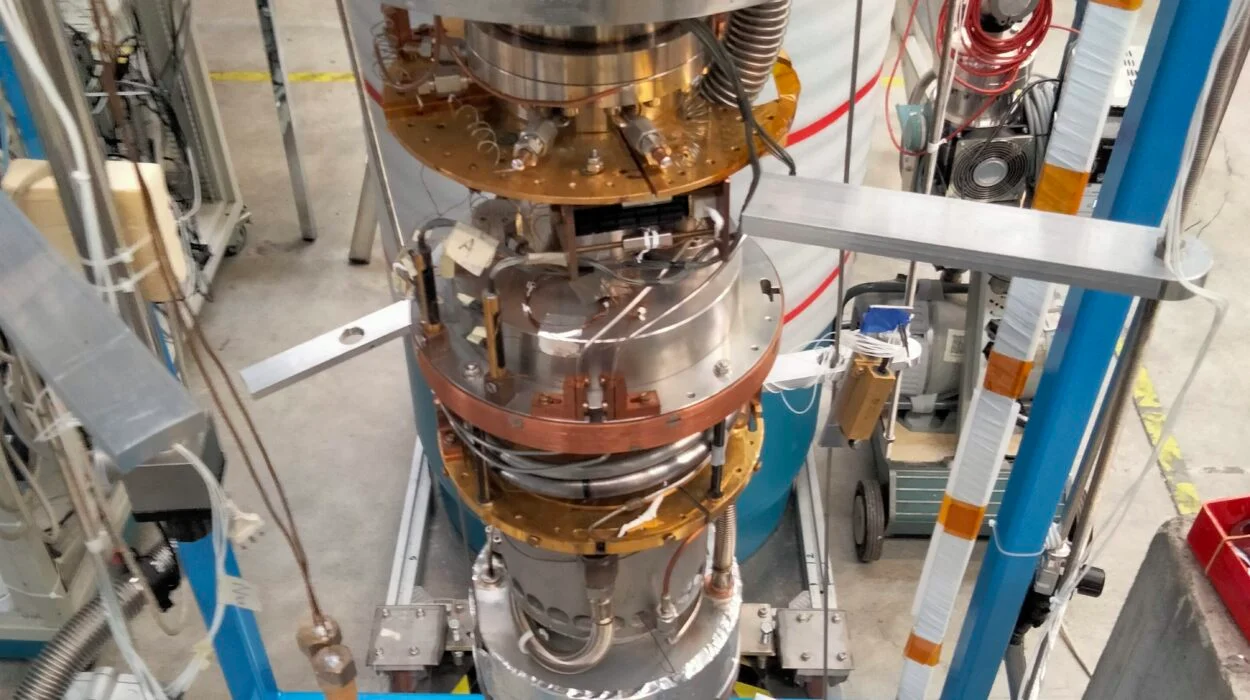

In the modern realization of Einstein’s proposal, Pan and his colleagues replaced abstract slits and springs with a remarkably simple and precise system. The particle was a photon, the quantum particle of light. Acting as the single slit was a single rubidium atom trapped in place by an optical tweezer.

The atom was cooled until it reached its ground state in a three-dimensional harmonic potential. In this carefully prepared condition, the atom functioned as an ultralight beam splitter. Its momentum became entangled with the momentum of the incoming photon, and the uncertainty in its motion could be reduced to the scale of a single photon’s momentum.

By dynamically varying the depth of the optical tweezer, the researchers could tune the rubidium atom’s intrinsic momentum uncertainty. As they adjusted this uncertainty, the interference fringes produced by the photons grew sharper or blurrier. The behavior followed precisely what the complementarity principle and Bohr’s prediction demanded. The more accurately the momentum information was available, the more the interference pattern faded.

From a modern point of view, as the authors write, “the Einstein-Bohr interference visibility is determined by the degree of quantum entanglement in the momentum degree of freedom between the photon and the slit.” In other words, it is not simply measurement that matters, but the entanglement linking the photon and the atom that plays the decisive role.

Wrestling With Heat and Motion

Executing such a delicate experiment required confronting practical challenges that Einstein and Bohr never had to consider. One significant complication arose from heating of the atom. Frequency drifts in the focused lasers forming the optical tweezer caused the trap’s depth to ramp up and down, scattering incoming photons and warming the atom’s motion.

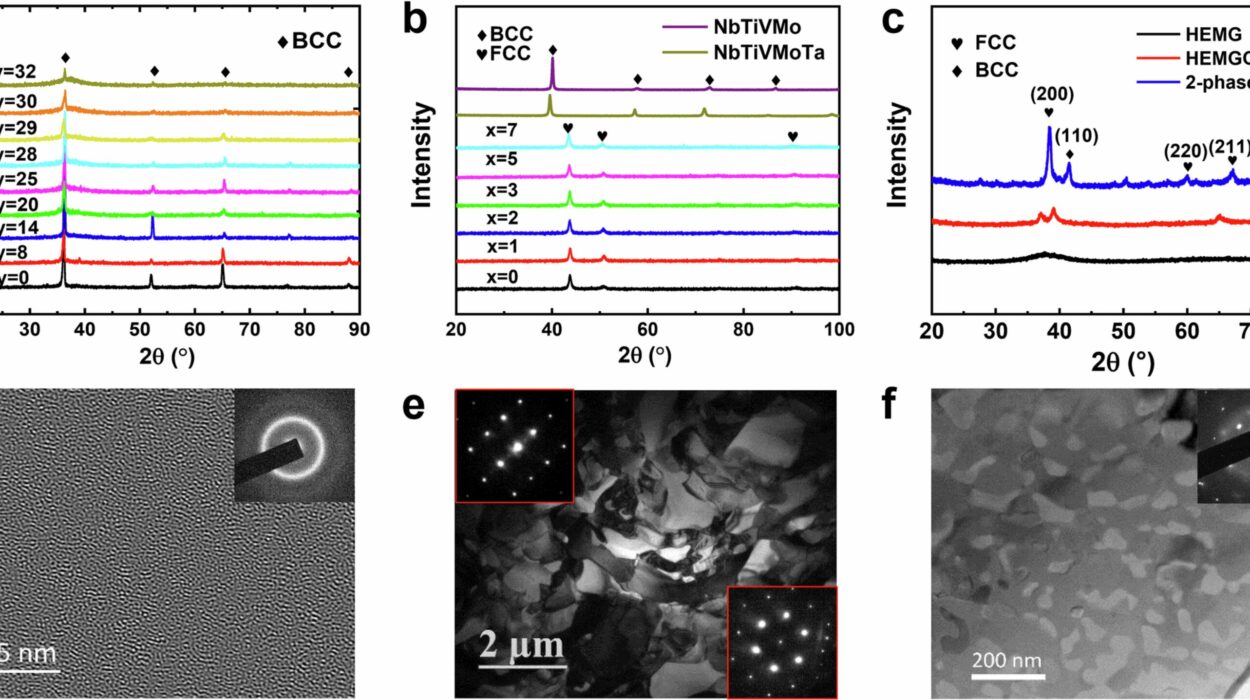

To correct for this effect, the team needed to measure the atom’s residual temperature in real time. They turned to scanning Raman spectroscopy, a technique that uses laser light to probe molecular vibrations. A laser of a single wavelength is directed onto a sample. Most of the light scatters elastically, without changing energy, but a small fraction scatters inelastically. The resulting change in frequency reveals information about chemical bonds, composition, and molecular interactions.

In this experiment, the ratio of the higher frequency to the lower frequency scattering was directly proportional to the thermal population of the atom’s vibrational modes, which follow a Bose-Einstein distribution. By measuring this ratio, the researchers could extract the atom’s temperature and calibrate their data accordingly. This careful accounting ensured that the observed blurring of the interference fringes was truly a quantum effect, not a byproduct of uncontrolled heating.

Watching the Quantum World Turn Classical

Beyond confirming Bohr’s argument, the experiment allowed the team to explore a subtle boundary in physics. They investigated the difference between the quantum limit and the classical heating of the atom’s motional states. This comparison makes it possible to observe the transition from quantum behavior to classical behavior, a process that remains one of the most intriguing and least settled aspects of quantum mechanics.

Complementarity itself has long been supported by experiments, but there is something uniquely powerful about realizing a famous thought experiment in the laboratory. It transforms an abstract debate into a tangible observation, allowing ideas once argued with words to be tested with data. The researchers now anticipate using quantum state tomography to determine the quantum state of the quantum slit directly, providing a more detailed probe of entanglement. They also plan to gradually increase the slit’s mass, enabling studies of how decoherence and entanglement interact as systems grow more classical.

Why This Old Argument Still Matters

At first glance, settling an argument between Einstein and Bohr might seem like an exercise in historical curiosity. Yet this experiment matters because it sharpens our understanding of the rules that govern the quantum world. Complementarity is not merely a philosophical stance; it shapes how information can be extracted from quantum systems and how quantum technologies must be designed.

By showing that interference visibility depends on entanglement between a particle and the measuring device, the work highlights the active role of measurement in quantum mechanics. It reinforces the idea that observers and instruments are not passive witnesses but participants in the phenomena they record. As researchers push toward more complex quantum systems and technologies, from precision measurements to quantum information processing, these principles become increasingly practical.

Einstein once hoped to prove that quantum mechanics was incomplete. Instead, experiments like this continue to reveal its internal consistency, even when tested by its most ingenious critics. The debate that began in a Brussels conference hall nearly a century ago is not merely a story of who was right or wrong. It is a reminder that science advances by daring questions, careful experiments, and the willingness to revisit even the most established ideas with fresh tools and sharper insight.

More information: Yu-Chen Zhang et al, Tunable Einstein-Bohr Recoiling-Slit Gedankenexperiment at the Quantum Limit, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/93zb-lws3