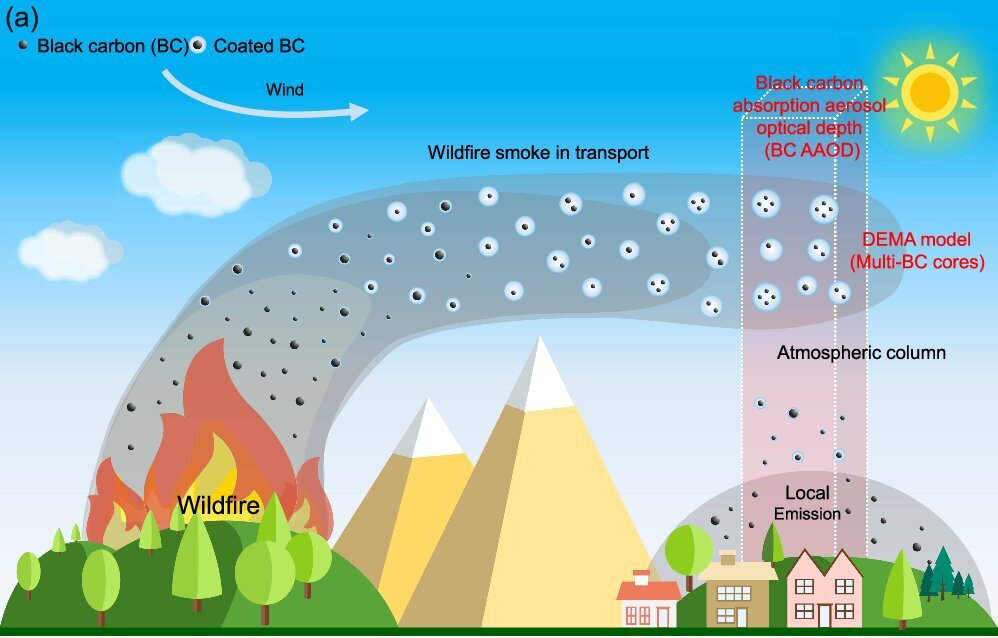

Far above burning forests, smoke does not simply fade into the sky. It travels, drifts, and transforms, carrying within it tiny particles that quietly reshape Earth’s climate. For decades, scientists believed they understood the structure of one of the most important of these particles: black carbon, the sooty residue released by wildfires and human activity. Yet a new international study suggests that this understanding has been incomplete, and that the climate consequences of this oversight may be far greater than previously recognized.

Researchers from The Education University of Hong Kong have joined colleagues from across the world to reveal that black carbon particles are often far more complex than climate models have assumed. Published in Nature Communications, the study shows that many of these particles do not carry a single carbon heart, but several. This seemingly subtle difference helps explain why black carbon has absorbed much more sunlight in the real atmosphere than models have been able to predict.

The Simple Shape That Shaped Climate Models

For years, global climate simulations relied on an elegant and convenient idea. Black carbon particles were treated as neat spheres with a single core of carbon at their center, wrapped in outer layers like a pearl in its shell. This “core-shell” structure made calculations manageable and offered a tidy way to estimate how much sunlight these particles absorb and convert into heat.

This approach shaped how scientists assessed the warming effects of black carbon worldwide. Yet it also carried a hidden assumption: that each particle contained only one core. As measurements accumulated, a troubling gap emerged. Observations in the real atmosphere consistently showed that black carbon absorbed roughly 50% more light than models predicted. The discrepancy lingered, unresolved, like a shadow that refused to align with the theory casting it.

A Closer Look Inside Wildfire Smoke

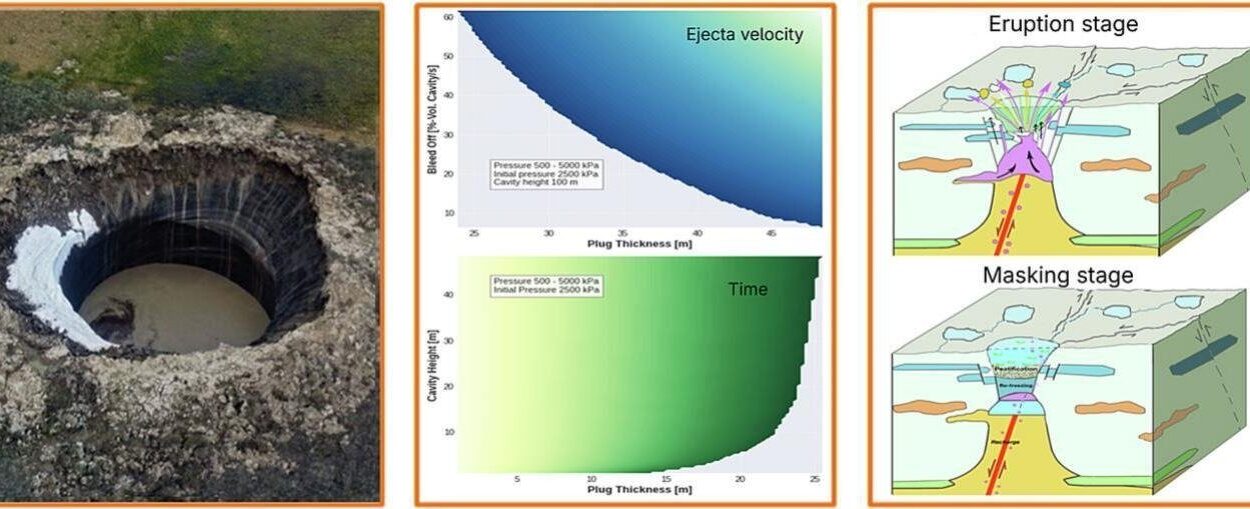

The answer began to emerge during fieldwork conducted in Yunnan’s wildfire season. There, researchers combined atmospheric sampling with advanced electron microscopy, peering into the internal architecture of particles carried long distances from their fiery origins. What they saw challenged the traditional picture.

About one-fifth, or 21%, of black carbon particles in long-range transported wildfire smoke contained not one core, but two or more. These multi-core particles were especially common among larger aerosols exceeding 400 nanometers in diameter. Instead of a single carbon center, these particles resembled clusters formed through collision and coalescence, with individual cores often exceeding 200 nanometers in size.

This structure had largely gone unnoticed in global climate models. Yet its implications were profound. If black carbon particles commonly carry multiple cores, their ability to absorb light changes dramatically.

The Physics of Crowded Cores

Black carbon does not merely float passively in the air. It interacts with sunlight, trapping energy that would otherwise reflect back into space. The internal arrangement of carbon within a particle determines how effectively it performs this role.

Previous theories assumed that black carbon “ages” mainly by accumulating layers on a single core. The new findings show that aging can also involve particles merging together, creating composite structures with multiple cores inside a shared обол. These crowded interiors enhance light absorption, offering a compelling explanation for why real-world measurements have long exceeded model predictions.

As Dr. Chen Xiyao, lead author of the study, explained, “The mixing state of BC is fundamental to understanding its climate effects. Ignoring coagulation and multi-core structures impedes accurate assessment and policy development regarding BC’s role in climate change.”

Teaching Models to See What Microscopes See

Identifying multi-core particles was only the beginning. The researchers faced a second challenge: translating nanoscale observations into global climate predictions. To do this, they turned to machine learning.

The team developed a machine learning emulator capable of quantifying how multi-core structures enhance light absorption. This emulator was then incorporated into a global atmospheric model, allowing the scientists to simulate how these particles behave across the planet.

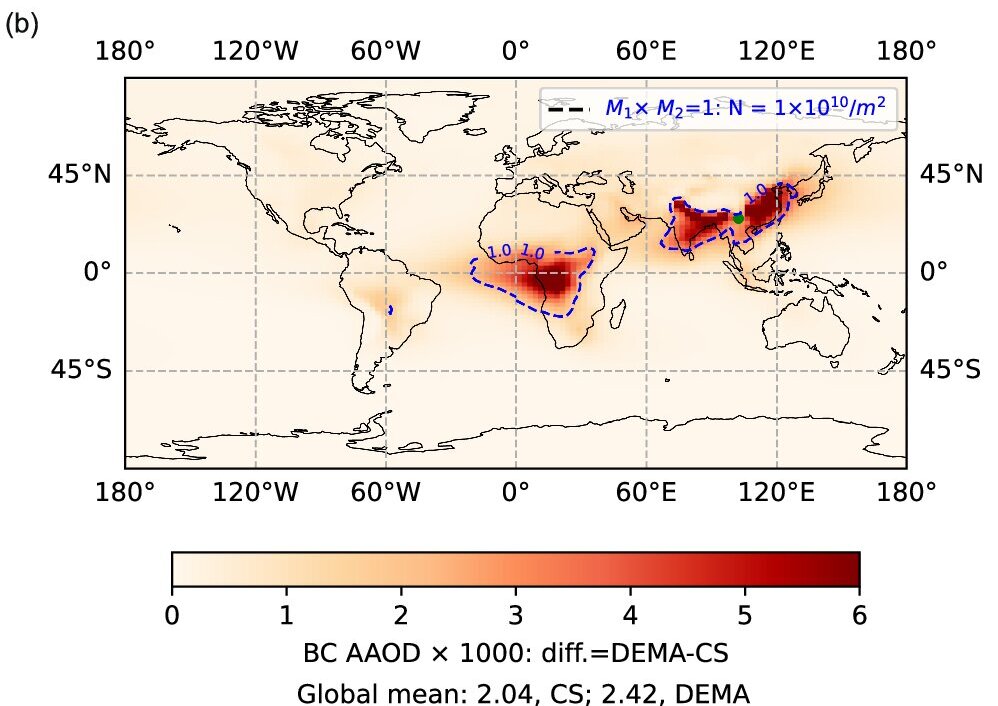

The results were striking. Multi-core black carbon particles were found to contribute to a 19% increase in global average black carbon absorption. The effect was especially pronounced in wildfire-affected regions, including Southeast Asia, southwestern China, the Tibetan Plateau, Southern Africa, and North America. In these areas, the overlooked structure of black carbon had been quietly amplifying warming.

A Global Collaboration Across Scales

The study was led by Professor Weijun Li from the School of Earth Sciences at Zhejiang University and brought together experts from the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong, China, the United States, the United Kingdom, Israel, Japan, and South Korea. Their expertise spanned atmospheric science, electron microscopy, global climate modeling, air pollution, and Earth system science.

Dr. Joseph Ching, assistant professor in the Department of Science and Environmental Studies at EdUHK, played a pivotal role in the atmospheric modeling component. By integrating particle-level measurements with optical simulations, global climate models, and machine learning, the team built a bridge between what microscopes reveal and what climate models must account for.

Professor Li described the significance of this integration, stating, “Our nanoscale observations have identified abundant multi-core black carbon particles in both wildfire and urban environments—structures previously unrepresented in climate models. By refining our algorithms, we have simulated their enhanced optical absorption and quantified their contribution to global warming, enabling more precise evaluation of black carbon’s climate impact. This study provides a more solid foundation in atmospheric science for climate governance and global cooperation.”

Wildfires, Warming, and a Growing Urgency

The timing of this discovery could not be more critical. Wildfires are becoming deadlier and more costly, with half of the 200 most damaging fires since 1980 occurring in just the last decade, according to data by global re-insurer Munich Re quoted by the media. As wildfire activity increases under ongoing global warming, so too does the release of black carbon into the atmosphere.

Black carbon is already recognized as a major contributor to climate change. Co-author Professor Mark Jacobson of Stanford University emphasized that the new research reinforces black carbon’s role as the second-leading contributor to global warming. Understanding its true behavior is therefore essential, not only for scientific accuracy but for shaping effective mitigation strategies.

Rethinking the Future of Climate Modeling

The researchers argue that climate models must evolve. By explicitly incorporating the multi-core mixing state of black carbon, future simulations can offer more accurate assessments of radiative forcing, the measure of how particles alter Earth’s energy balance. This refinement would guide more informed emission reduction strategies and improve the reliability of climate projections.

Dr. Joseph Ching highlighted the broader impact of the work, noting that the integrated approach advances understanding of black carbon’s warming effects and supports the development of more effective climate policies. Accurate modeling, in this sense, becomes a tool not just for prediction, but for governance.

Why This Research Matters

At its heart, this study tells a story about perspective. When black carbon particles were viewed from a distance, they seemed simple. When examined closely, they revealed hidden complexity with global consequences. By recognizing and accounting for that complexity, scientists can close a long-standing gap between observation and theory.

The findings matter because climate policy depends on trust in models, and models depend on faithful representations of reality. As wildfire smoke continues to circle the globe, carrying multi-core particles that absorb more heat than expected, understanding their true nature becomes essential. This research strengthens the scientific foundation for climate action, informs international cooperation, and contributes to global goals related to health, sustainable cities, and climate resilience.

In revealing what lies inside a particle of smoke, the study reshapes how we see its role in warming the planet. It reminds us that even the smallest structures can have outsized effects, and that progress in climate science often begins by looking closer than ever before.

More information: Xiyao Chen et al, Locating the missing absorption enhancement due to multi‒core black carbon aerosols, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65079-2