In a cavern of steel, electronics, and chilled liquid argon beneath the plains of Illinois, physicists have been listening for one of the faintest murmurs in nature. Neutrinos, nearly massless particles that slip through planets, people, and entire stars without leaving a trace, were once suspected of hiding a secret companion. For years, puzzling signals from earlier experiments hinted that something unseen might be at work, a new and elusive kind of neutrino that would quietly reshape our understanding of reality.

Now, after years of careful listening, the MicroBooNE experiment at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab National Accelerator Laboratory has delivered a clear message. The evidence does not support the existence of this hypothesized “sterile” neutrino. The finding, reported in a paper published in Nature, closes one door while sharpening the focus of an ongoing scientific mystery.

For Maria Brigida Brunetti, an assistant professor in the University of Kansas Department of Physics & Astronomy and a co-author on the study, the result is not an ending but a refinement. It narrows the search for answers and clarifies where physicists must look next. As she put it, “This experiment is part of a broad international effort to study neutrinos.”

The Particles That Pass Through You Without a Trace

Neutrinos are everywhere, though they announce themselves almost not at all. They are among the most abundant particles in the universe, second only to light itself. Yet their ghostlike nature makes them extraordinarily difficult to study, and that difficulty is precisely what makes them so fascinating.

“They are the second most abundant particle, after light. They travel through everything; they travel through us. Tens of trillions of them pass through your body each second, but you don’t notice them because they don’t interact much at all—they can only interact through the weak and gravitational forces,” Brunetti said.

This near-invisibility places neutrinos at the edge of human perception and experimental capability. They do not carry electric charge, and they almost never collide with atoms. To catch even a few, scientists must produce intense beams and build massive detectors designed to register the rare moments when a neutrino finally interacts with matter. Because of these challenges, neutrinos remain among the least understood fundamental particles, despite their overwhelming abundance.

That ignorance has consequences. Neutrinos are woven into the Standard Model of particle physics, the framework that describes the fundamental building blocks of reality. Any surprise in their behavior has the potential to point toward new physics beyond that model.

A Strange Talent for Shape-Shifting

One of the most intriguing properties of neutrinos is their ability to change identity as they travel. Physicists call these identities “flavors,” and there are three known kinds. A neutrino born as one flavor can later be detected as another, a phenomenon that initially stunned the scientific community and remains a central focus of modern particle physics.

“One of their peculiar features is that there are three types of them called flavors, and as they travel they transform between each other,” Brunetti said. “This phenomenon is called neutrino oscillation.”

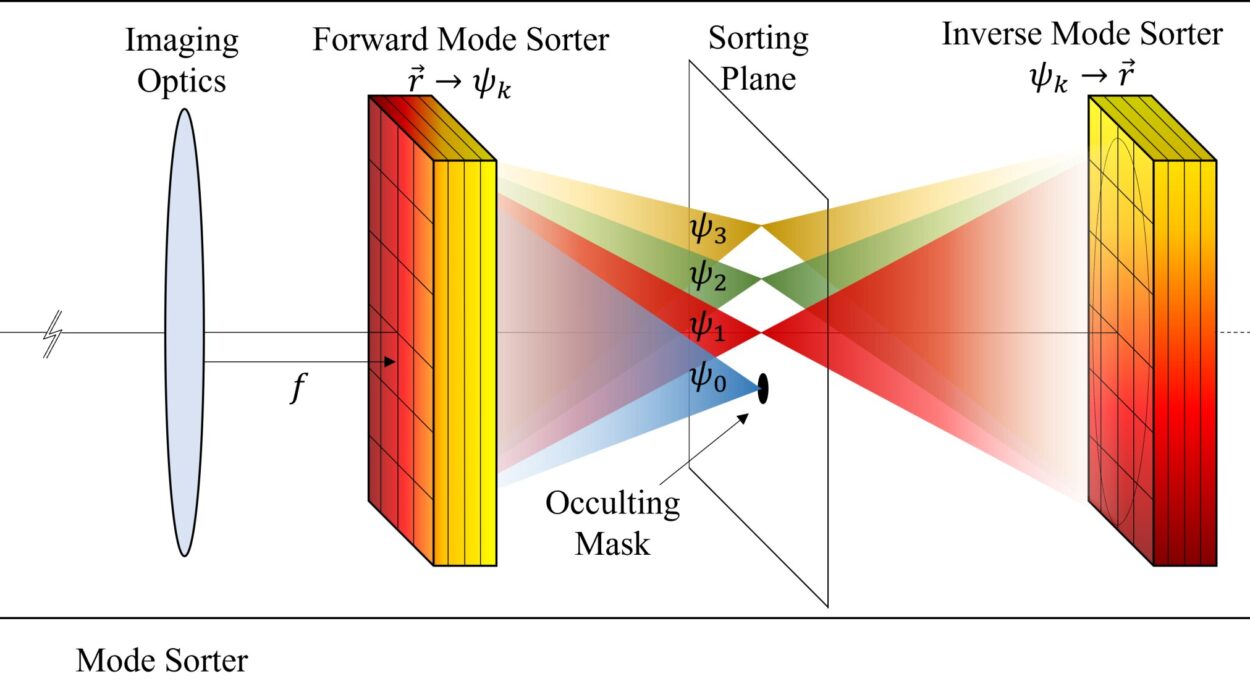

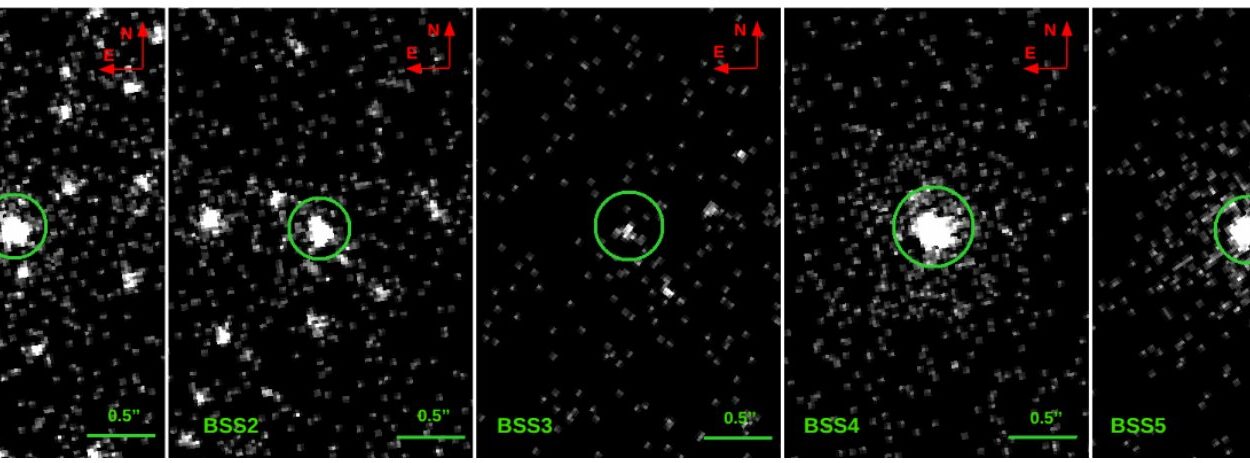

Experiments like MicroBooNE are designed to study these oscillations in exquisite detail. Neutrinos are generated in powerful accelerators and sent toward detectors placed some distance away. By comparing what scientists expect to see with what they actually observe, they can infer how neutrinos have transformed during their journey.

Because neutrinos interact so rarely, the process requires patience and scale. “Because neutrinos only interact weakly, we need to produce a lot of them in intense beams in order for a few of them to interact in our liquid argon time projection chamber (LArTPC) detectors,” Brunetti explained.

Photographing the Nearly Invisible

The MicroBooNE detector is not a camera in any ordinary sense, yet it produces images of extraordinary clarity. Inside its liquid argon chamber, neutrinos occasionally collide with argon atoms, setting off cascades of charged particles. These particles rip electrons from nearby atoms as they pass, leaving behind trails that can be captured and reconstructed.

“These detectors allow us to capture very high-resolution representations of particle interactions,” Brunetti said. “In the detector, neutrinos interact with the liquid argon atoms and produce charged particles. As these particles travel through, they strip the argon atoms of electrons. We put an electric field in the detector, and all these electrons drift toward the readout elements where we collect the signal.”

In MicroBooNE, those readout elements take the form of multiple planes of finely spaced wires. By recording which wires are struck and precisely when the electrons arrive, physicists can reconstruct the event in two or even three dimensions.

“From the information on which wires or pixels were hit by the drifted electrons and from the electrons’ arrival time, you can build 2D images or 3D representations,” Brunetti said. “These are high-resolution—we really can photograph the interaction in very high detail.”

Turning these intricate images into physical insight requires sophisticated software. Brunetti’s group at the University of Kansas specializes in tools such as the Pandora event reconstruction, which interprets the images to identify where a neutrino interacted, what particles emerged, and how much energy they carried. This painstaking work allows scientists to analyze vast and complex datasets with confidence.

The Ghost Particle That Might Have Been

The sterile neutrino entered the story as a tempting solution to an enduring puzzle. Earlier experiments, including MiniBooNE and LSND, had reported anomalous results that did not fit neatly within the framework of three neutrino flavors. One possible explanation was the existence of a fourth kind of neutrino, one that would be even more elusive than the others.

“Sterile neutrinos would therefore only feel one of the fundamental forces, gravity. The experiment was looking for new physics,” Brunetti said.

If such a particle existed, it would subtly alter the pattern of neutrino oscillations observed in experiments like MicroBooNE. The detector should have seen telltale deviations from expected behavior, fingerprints of neutrinos slipping into and out of this hidden state.

But those fingerprints never appeared.

“But if this was the case, that there’s a fourth type of neutrino we don’t yet know of, this would’ve changed what we saw in our experiment. Instead, MicroBooNE didn’t confirm the anomalies that the previous MiniBooNE and LSND experiments observed, and it ruled out several possible explanations, including one in terms of oscillations to a sterile neutrino in this paper.”

The conclusion is careful but firm. The MicroBooNE results do not support sterile neutrinos as the explanation for the earlier anomalies. In effect, one of the most discussed possibilities has been largely ruled out.

Narrowing the Mystery Rather Than Ending It

Science rarely advances by dramatic revelations alone. Just as often, progress comes from eliminating possibilities, tightening constraints, and sharpening questions. Brunetti emphasizes that this result does exactly that.

The anomalies observed in earlier experiments remain unexplained, but the field now knows more clearly where the answer is not. By excluding sterile neutrino oscillations as a likely cause, MicroBooNE has focused attention on alternative explanations that must now be explored with equal rigor.

This narrowing is not a setback. It is a necessary step in a disciplined search for truth, guided by data rather than desire.

Following Neutrinos on Longer Journeys

MicroBooNE is part of a larger effort known as the Short-Baseline Neutrino program at Fermilab, designed to study neutrinos over relatively short distances. But the story does not stop there. Brunetti and her colleagues are also deeply involved in the next generation of experiments, including the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment, or DUNE.

“For MicroBooNE, this is part of what we call the Short-Baseline Program at Fermilab,” Brunetti said. “You can either design experiments that look at a short-baseline oscillation, meaning the neutrinos don’t travel as much, or you can study experiments that let the neutrinos travel a longer distance, which is what DUNE will do.”

DUNE will send neutrinos on an 800-mile journey from Fermilab to a far detector in South Dakota, while also using near detectors to study the beam before it oscillates. The experiment will employ larger and more sophisticated LArTPC detectors and a neutrino beam spanning a broad range of energies.

“The combination of the long baseline and the broad neutrino energy range will give DUNE unique capabilities to study oscillations,” Brunetti said.

With more than 1,400 collaborators worldwide, DUNE represents the forefront of neutrino research, alongside another major effort in Japan. Together, these experiments aim to answer some of the most fundamental questions in particle physics.

Why This Result Truly Matters

At first glance, ruling out a particle that may not exist can seem anticlimactic. Yet the MicroBooNE findings carry deep significance. They demonstrate the power of modern detectors and analysis techniques to confront longstanding anomalies with unprecedented clarity. They reinforce confidence in experimental methods that can quite literally photograph the interactions of particles that pass unnoticed through the human body by the trillions.

More importantly, this result exemplifies how science advances. By rigorously testing a bold hypothesis and finding it unsupported, researchers have refined the boundaries of the possible. They have narrowed the mystery without closing it, ensuring that future investigations are guided by sharper questions and firmer ground.

Neutrinos remain enigmatic messengers from the deepest workings of the universe. Understanding how they oscillate, how much mass they carry, and whether they behave differently from their antimatter counterparts could reshape our picture of fundamental physics. The MicroBooNE experiment has shown that even silence can speak volumes, and that listening carefully to what nature does not say can be just as important as hearing what it does.

More information: et al, Search for light sterile neutrinos with two neutrino beams at MicroBooNE, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09757-7