For decades, the caves of western Nevada have carried a reputation that felt almost mystical. Archaeologists and storytellers alike described the lower Lahontan drainage basin, or LLDB, as a place apart, where ancient people chose to lay their dead inside caves again and again over thousands of years. The idea lingered that something spiritually unique was happening there, something that set this landscape apart from the rest of the Great Basin.

But science has a way of returning to old stories and asking them, gently but firmly, to show their evidence.

In a study published in American Antiquity, archaeologist Dr. David Madsen and his colleagues did just that. They followed the trail of burials not only into the Lahontan caves, but beyond them, into neighboring lands. What they found reshaped a long-held belief and revealed a quieter, more human explanation written into the geography itself.

Following the Dead Across an Ancient Landscape

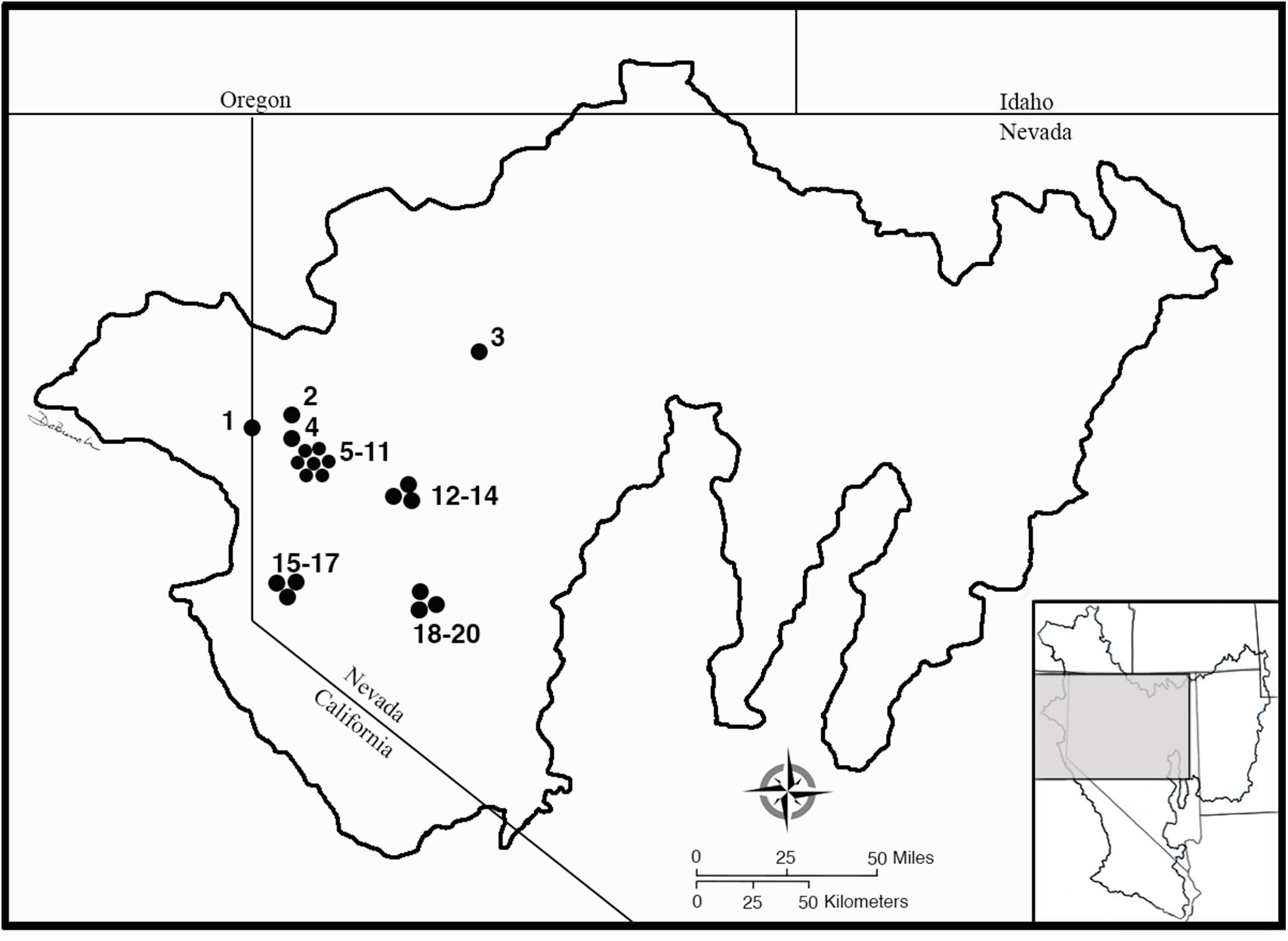

The Intermountain West stretches across western North America, framed by mountain ranges and dotted with basins that once held vast lakes. Two of the largest of these basins are the lower Lahontan drainage basin in western Nevada and the Bonneville Basin in western Utah. For years, these two landscapes were treated differently in archaeological narratives.

The LLDB was thought to be special. Earlier research suggested that Paleoindians began burying their dead in Lahontan Basin caves at least 11,000 years ago, and kept doing so for millennia. This pattern was described as unusually persistent and rarely seen elsewhere, giving the impression of a regional burial tradition unlike any other.

Dr. Madsen and his team decided to test that idea directly. If cave burials were truly unique to the LLDB, then neighboring regions should show a different story. So they turned their attention to the Bonneville Basin, just to the east, and began assembling evidence from caves, rock shelters, and open-air sites alike.

They were not just counting burials. They were searching for patterns, choices, and habits that could reveal how ancient people understood death, place, and daily life.

Inside the Caves Where Life Once Happened

In the Bonneville Basin, the researchers identified 18 cave burials containing a minimum of 91 human burials. That number, they emphasize, is almost certainly an underestimate. Some burials were never excavated, while others were disturbed or stolen long ago by vandals.

What surprised the researchers was not just the number, but the context. Nearly all of these cave burials were found in places where people once lived. These caves and rock shelters were residential sites, spaces where daily activities unfolded alongside sleeping, tool-making, and food preparation.

Death, in these places, did not seem separated from life.

Only two caves broke this pattern. Lehman Cave and Snake Creek Cave were natural trap caves, formations that captured individuals who entered and could not escape. These sites served as special-purpose burial locations, containing the remains of over three dozen individuals without evidence of everyday occupation.

The presence of these exceptional caves mattered, but they did not define the whole story. Most burials were woven into living spaces, suggesting a practical and familiar relationship with death rather than an exclusively ceremonial one.

The Ground Beyond the Cave Mouth

Caves, however, were only part of the picture.

When the researchers looked at open-air sites, they found something striking. Burials in these locations vastly outnumbered those in caves. While it was not possible to count them precisely, the number of open-air burials exceeded cave burials by an order of magnitude or more.

People were buried in houses, in middens near homes, and in isolated open spaces. Caves and rock shelters were just one option among many.

This broader perspective made one thing clear. Focusing only on caves risks missing the complexity of burial practices across the landscape. Death followed people wherever they lived and worked, adapting to the spaces they used rather than adhering to a single sacred formula.

Two Basins, One Shared Pattern

When the Bonneville Basin data were compared with the LLDB, the similarities became impossible to ignore. The researchers added three cave and rock shelter burials and two marginal sites from the LLDB that had not been included in earlier reports, enriching the dataset even further.

Both regions showed occupational histories spanning approximately 14,000 to 13,000 years. Across that vast stretch of time, burial locations were remarkably diverse. People were laid to rest in houses, near houses, in open-air sites, in caves, and in rock shelters where daily life took place. Special-purpose burial caves appeared only sometimes, not as a dominant or defining practice.

Both basins also showed an increase in burials around 5,000 calibrated years before present, suggesting broader demographic or environmental changes rather than a sudden shift in belief.

The conclusion was clear. Cave and rock shelter burials were not a rare or unusual practice confined to the LLDB. They were a regular feature of Great Basin life.

Why Lahontan Still Stands Out

If burial practices were so similar, why did the LLDB gain a reputation for uniqueness?

The difference, the researchers argue, lies in numbers, not beliefs.

The LLDB contains nearly twice as many cave burials as the Bonneville Basin, including more special-purpose caves without evidence of occupation. Rather than signaling a distinct spiritual tradition, this likely reflects higher population levels throughout the Holocene.

The reason for those higher populations may be rooted in water.

The LLDB supported larger wetlands, creating productive marsh environments that could sustain repeated visits. According to Dr. Bryan Hockett, one of the study’s authors, these marshes allowed people to return to the same places year after year. In a landscape filled with hundreds of dry caves, this created practical opportunities.

Mobile foragers could store equipment in caves, retrieve it later, and avoid carrying everything with them all year. Some of those caves, over time, also became places of burial. What looks spiritual from a distance may, up close, be deeply logistical.

Living Descendants and Lingering Boundaries

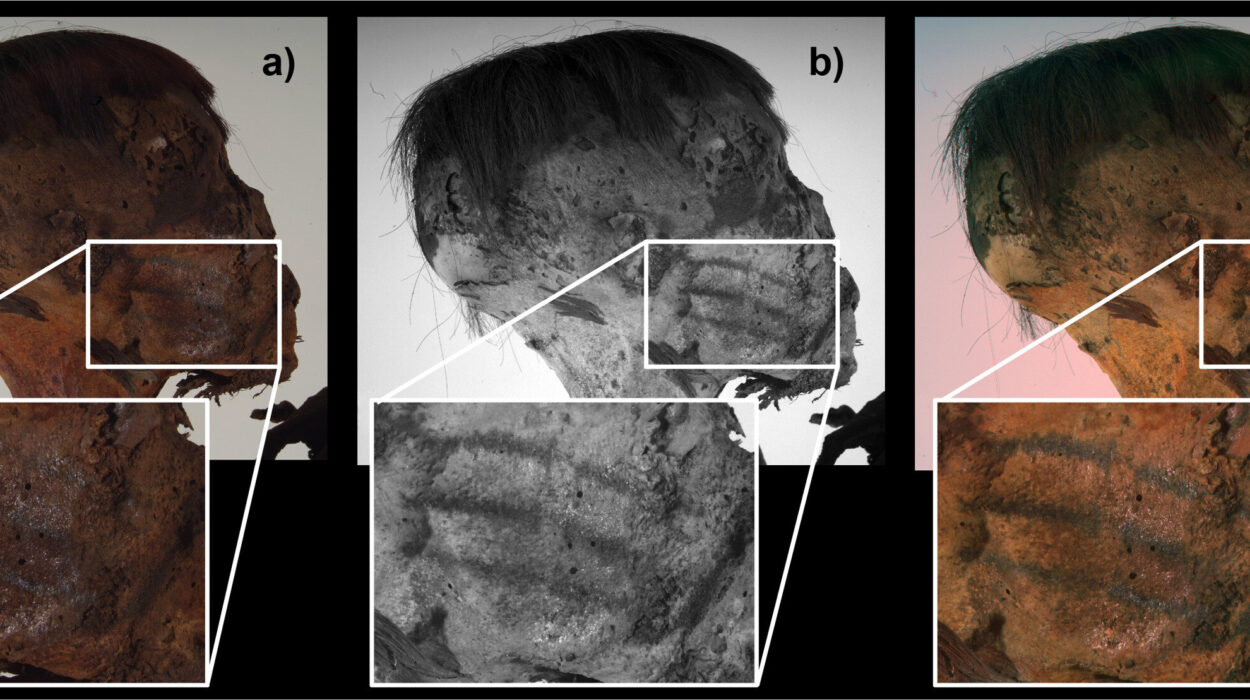

Today, Northern Paiute people, part of the Numic language family, avoid many of these burial caves. The avoidance is rooted in fear and respect for ancestors, a powerful reminder that these sites are not relics of a vanished world but places with ongoing cultural meaning.

Archaeological evidence and oral traditions suggest that the Washoe people, part of the Hokan-stock language family, originally occupied many of these sites. Other groups, including Penutian-speaking tribes such as the Maidu and Miwok, who now live exclusively in California, may have passed through or occupied the area at times.

According to Dr. Hockett, these shifting patterns fit within a larger story revealed by recent DNA studies. Human occupation in North America involved both long-term stability and large-scale migrations, particularly in the 1,000 to 2,000 years before European contact. Territories changed, people moved, and landscapes accumulated layers of memory.

Why This Research Matters

This study does more than correct a regional detail in archaeological textbooks. It reminds us how easily patterns can be mistaken for meaning.

By showing that cave burials were a widespread Great Basin tradition, not a spiritually unique hallmark of the LLDB, the research reframes how we interpret ancient behavior. Burial choices were shaped by population density, resource availability, and landscape features, not solely by distinct belief systems.

That matters because it humanizes the past. Instead of imagining ancient people as following rigid, mysterious rituals tied to specific places, we see them adapting thoughtfully to their environments. They buried their dead where life happened, where resources were reliable, and where movement across the land made sense.

In the end, the caves of Lahontan are not less meaningful for losing their aura of uniqueness. They are more meaningful. They become part of a shared human story across the Great Basin, where survival, memory, and respect for the dead were shaped not by isolation, but by connection to land and community over thousands of years.

Study Details

David Madsen et al, Cave/Rockshelter Burials in the Great Basin, American Antiquity (2026). DOI: 10.1017/aaq.2025.10148