When astronomers first spotted CEERS2-588, it appeared as a small, distant glow tucked deep into images from the early universe. At first glance, it looked like one more fragile newborn galaxy forming not long after the Big Bang. But something about it didn’t fit the script.

This galaxy shines intensely in ultraviolet light, far brighter than expected for an object that existed only 400 million years after the Big Bang. Even more puzzling, it belongs to a time when galaxies were supposed to be small, chemically primitive, and still learning how to form stars efficiently. CEERS2-588 seemed far too confident for its age.

So astronomers from the University of Tokyo, led by Yuichi Harikane, decided to take a closer look using one of the most powerful space observatories ever built. They turned the James Webb Space Telescope toward this stubborn glow, determined to uncover what kind of galaxy it really was.

What they found rewrote expectations about how fast galaxies could grow up in the early universe.

Looking Back Nearly to the Beginning of Everything

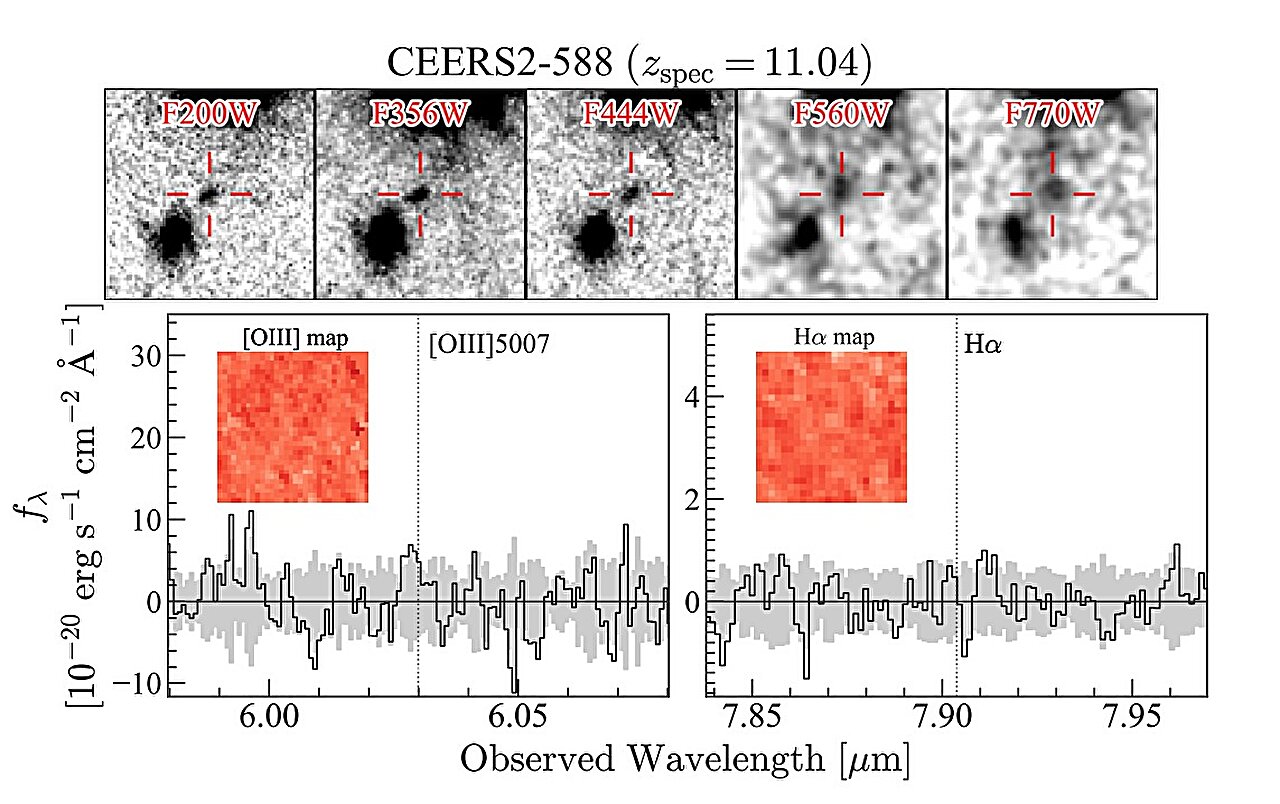

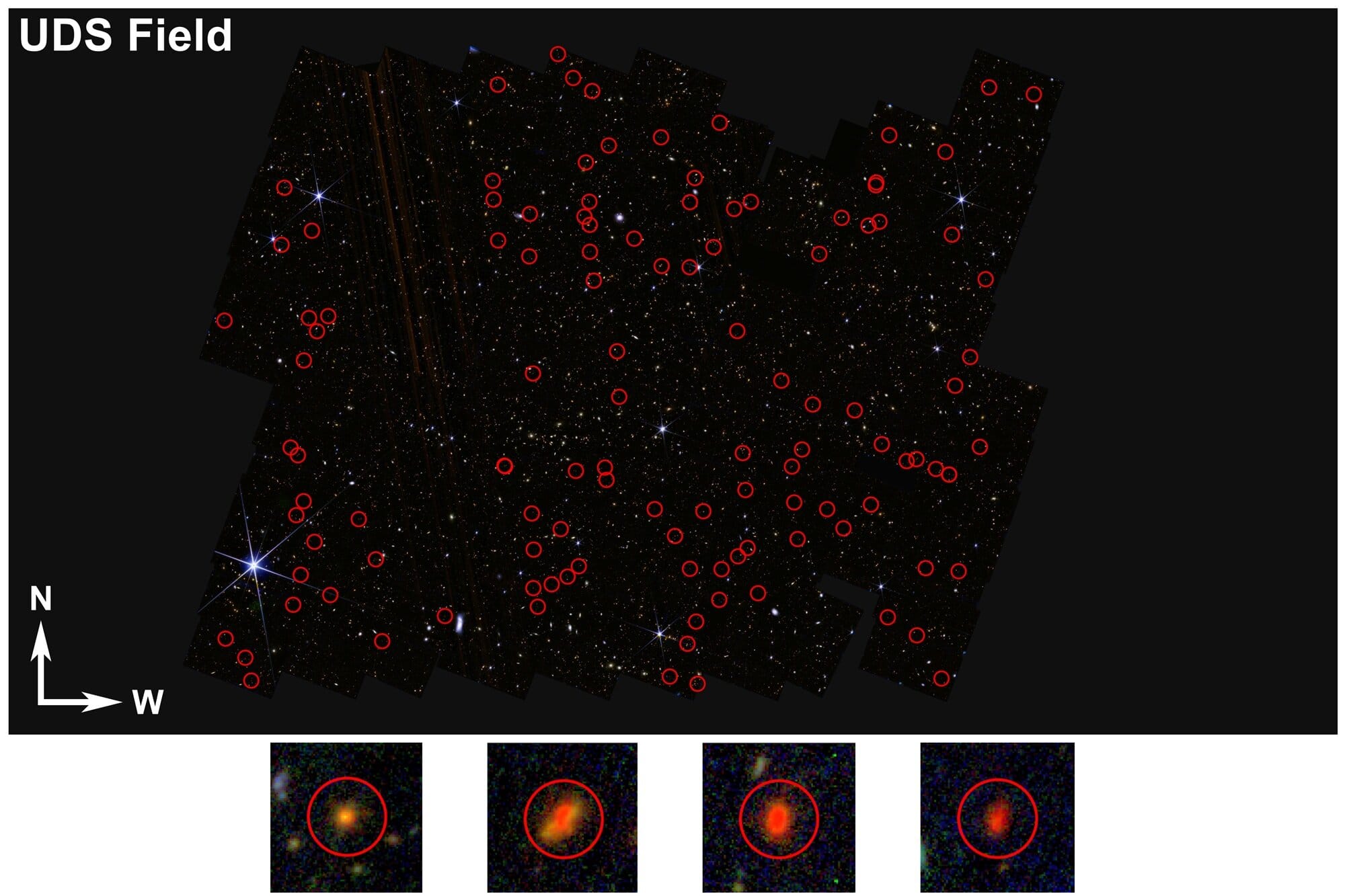

CEERS2-588 was first identified in 2022 through the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science project, known as CEERS. It was classified as a Lyman-break galaxy, a type of galaxy identified by how its light drops off sharply at certain ultraviolet wavelengths. That signature places it at an astonishing redshift of 11.04, meaning its light has traveled for more than 13 billion years to reach us.

At that distance, astronomers are not just seeing far away. They are seeing far back in time, into an era when the universe itself was young and chaotic.

Even then, CEERS2-588 stood out. It was one of the most ultraviolet-luminous galaxies known at such an extreme redshift. It also appeared surprisingly extended, with an effective radius of about 1,470 light years, suggesting it was not a tiny clump of stars but a more developed structure.

Yet many of its most important properties, including its true mass, were still uncertain. To resolve that mystery, the team used JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI, which can detect light that older stars and dust emit, revealing how much material a galaxy truly contains.

A Galaxy That Gained Weight Fast

The MIRI observations delivered a shock.

CEERS2-588 turned out to have a mass of approximately 1.26 billion solar masses. For a galaxy existing at a redshift greater than 10.0, this is enormous. More striking still, there was no evidence of active galactic nucleus activity, meaning the galaxy’s brightness could not be explained by a supermassive black hole devouring material at its center.

This makes CEERS2-588 the most massive known galaxy at such an early cosmic time without an active galactic nucleus powering its glow.

The galaxy is not just heavy. It is actively forming stars at a measured rate of 8.2 solar masses per year. In the early universe, that kind of star production is intense, especially for a system that already carries so much mass.

Taken together, the numbers painted a picture of a galaxy that assembled itself quickly and efficiently, defying the idea that early galaxies grew slowly and cautiously.

The Chemical Clue That Shouldn’t Exist Yet

If the mass was surprising, the galaxy’s chemistry was downright unsettling.

Astronomers measured the gas-phase metallicity of CEERS2-588 and found it to be close to solar, meaning its gas contains chemical elements at levels similar to those found in our own Sun. In astronomy, “metals” include all elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, and they are forged inside stars and spread through galaxies over time.

In theory, galaxies at redshifts above 10.0 should not have had enough time to produce and recycle these elements in large quantities. Yet CEERS2-588 appears already enriched.

Such massive, metal-rich systems have not previously been reported at this epoch, and existing theoretical models do not predict their existence. This galaxy is not just early. It is chemically mature far ahead of schedule.

It is as if the universe handed CEERS2-588 a shortcut, allowing it to race through evolutionary stages that other galaxies take much longer to complete.

A Life Story Written in Bursts, Not a Steady Line

To understand how this galaxy became so massive and metal-rich so quickly, the team reconstructed its past using spectral energy distribution fitting, a technique that analyzes how a galaxy emits light across different wavelengths.

The results revealed a dramatic history.

Star formation in CEERS2-588 appears to have begun 100 to 300 million years after the Big Bang, meaning it started building stars remarkably early. But instead of steadily forming stars at a consistent pace, the galaxy’s star formation history shows sharp changes.

Within the last 10 million years, its star formation rate experienced a sudden decline, a behavior that contrasts with other galaxies observed at similar redshifts. This pattern suggests that CEERS2-588 does not grow smoothly. It grows in bursts, with periods of intense activity followed by rapid quieting.

These bursts would produce large numbers of massive, short-lived stars that flood the galaxy with ultraviolet light, explaining its extraordinary brightness.

When Efficiency Changes the Rules of the Early Universe

The researchers concluded that CEERS2-588 fits a scenario in which early galaxies experience highly bursty star formation, driven by high star formation efficiency. In this view, galaxies in the early universe could convert gas into stars far more effectively than previously assumed, at least for short periods.

This efficiency would rapidly increase a galaxy’s mass and enrich its gas with heavy elements, even in a very young cosmos. It would also explain why CEERS2-588 shines so brightly in ultraviolet light despite its age.

Rather than being an odd exception, CEERS2-588 may represent a class of early galaxies that grew fast, burned bright, and then shut down star formation more quickly than models predict.

As the researchers note, efficient starbursts appear to play a key role in producing the luminous galaxy population in the early universe.

Why This Galaxy Changes How We Think About Cosmic Beginnings

CEERS2-588 matters because it challenges the timelines astronomers have relied on to understand how the universe evolved.

The discovery shows that massive galaxies could form within the first few hundred million years of cosmic history and that their star formation could be both more efficient and more rapidly quenched than theoretical models suggest. It forces scientists to reconsider how quickly matter assembled, how fast stars enriched their environments, and how chaotic the early universe may have been.

This single galaxy suggests that the early universe was capable of producing complexity much sooner than expected. It hints that the first generations of galaxies were not always tentative builders but sometimes aggressive architects, rapidly shaping themselves before cosmic conditions changed.

By revealing what CEERS2-588 truly is, the James Webb Space Telescope has done more than study a distant object. It has opened a window onto a version of the early universe that is faster, richer, and far more dynamic than previously imagined.

Study Details

Yuichi Harikane et al, A UV-Luminous Galaxy at z=11 with Surprisingly Weak Star Formation Activity, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2601.21833