In the year 1181 AD, observers on Earth looked toward the heavens and witnessed a celestial anomaly. A “guest star” had appeared, shining with a sudden, startling brilliance that refused to fade. For six long months, this visitor lingered in the night sky, a silent witness to the passage of time before finally vanishing into the darkness. For nearly 850 years, the memory of that light existed only in ancient records, a cold case in the vast archives of the cosmos. It wasn’t until recently that astronomers rediscovered what they believe to be the skeletal remains of that ancient event. Dubbed supernova remnant (SNR) Pa 30, this cloud of cosmic debris should have looked like any other shattered star. Instead, it presented a profile so bizarre that it defied conventional explanation.

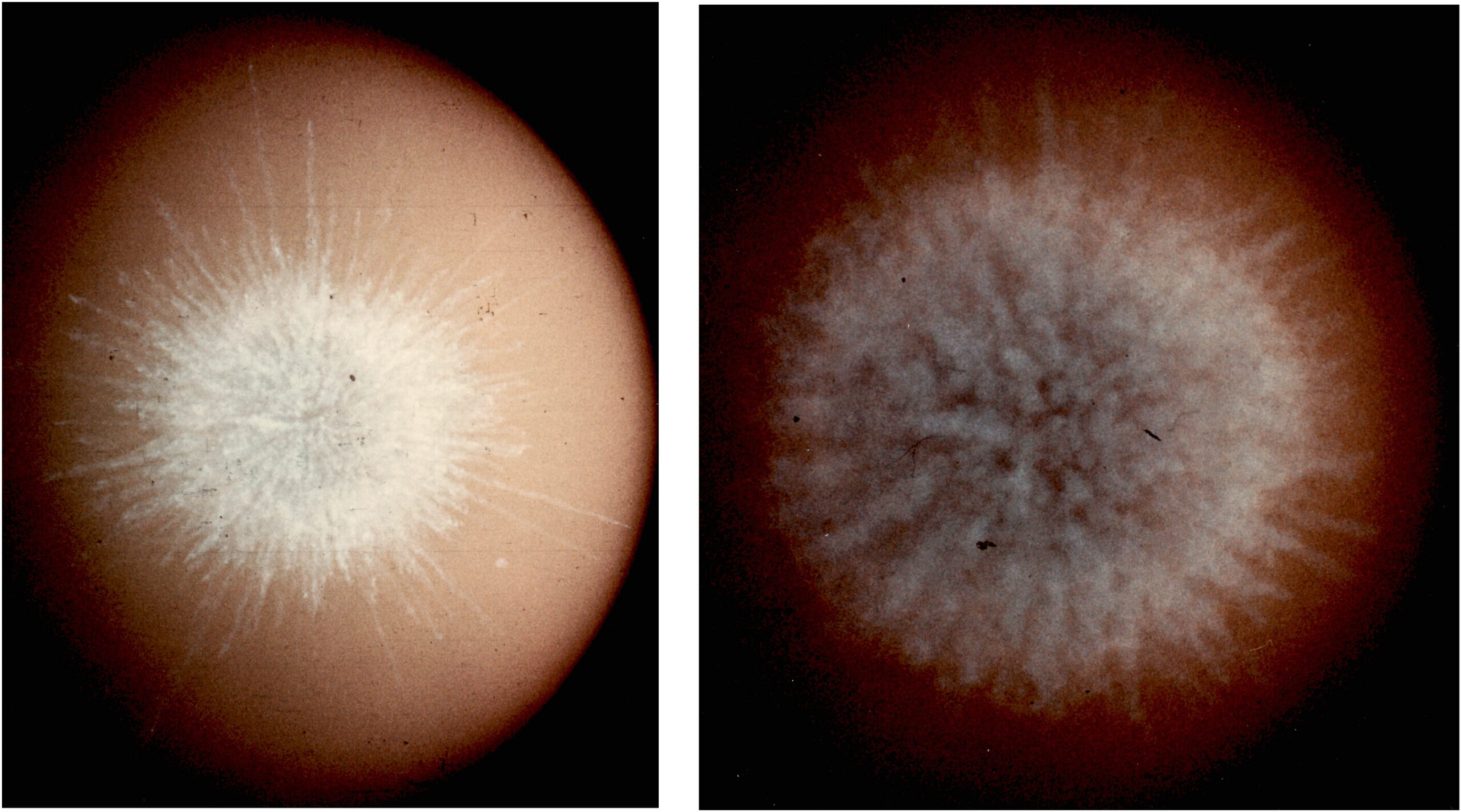

When researchers first turned their telescopes toward Pa 30, they didn’t see the typical, messy shell of an explosion. Instead, they found what has been described as a “firework-like morphology.” Imagine a grand finale frozen in a single frame of film, with thin, radial filaments of light screaming outward from a central point. This visual structure is incredibly rare among supernova remnants. For years, scientists struggled to understand how these thin, needle-like threads of matter could maintain their shape and persist across nearly a millennium without blurring into a chaotic cloud. The traditional models of how stars die simply couldn’t account for the persistence and precision of these frozen interstellar fireworks.

The Heart of a Zombie Star

The mystery of Pa 30 begins with the nature of the explosion itself. Most supernovae are the definitive end of a star’s life—a total, catastrophic demolition. However, a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters suggests that the event of 1181 was something much stranger: a Type Iax supernova. In this scenario, the “x” serves as a marker for a cosmic failure. The star did not complete its full explosion process. It was an unfinished blast, a celestial firecracker that fizzled out before the job was done.

Because the explosion was incomplete, it left behind a celestial paradox: a “zombie star.” This central white dwarf is the surviving core of the disaster, a ghostly remnant that refused to stay dead. Despite its battered state, this zombie star is far from quiet. It remains incredibly active, driving a ferocious stellar wind that screams into the vacuum of space at speeds exceeding 10,000 kilometers per second. It is this relentless, high-speed wind, rather than the initial blast of the supernova, that holds the secret to the firework display.

Sculpting the Void with Fluid and Fire

To understand how these delicate filaments formed, a team of researchers turned to complex hydrodynamical simulations. They wanted to see what happens when the high-speed winds of a zombie star collide with the “circumstellar medium” (CSM)—the slower, older layers of gas that the star drifted off during its earlier, more peaceful life. The interaction between these two forces is a delicate dance of fluid dynamics.

In the past, some scientists thought these patterns might be caused by two different types of fluid chaos: Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities (RTI) and Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities (KHI). To visualize these, think of RTI as what happens when a heavy fluid sits on top of a lighter one, causing “fingers” of material to poke through. KHI, on the other hand, is the swirling, wavy turbulence created when fluids of different speeds rub against each other, much like wind whipping up waves on the surface of the ocean.

The team’s model revealed a specific chemical and physical balance that explains why Pa 30 looks the way it does. They found that the firework-like filaments were the result of Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities occurring at the interface where the dense, fast-moving wind from the white dwarf slammed into the lower-density gas of the surrounding medium. Crucially, the model showed that the high density contrast between these two layers actually inhibited the Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities. In simpler terms, the difference in density was so great that it prevented the swirling turbulence from tearing the filaments apart. This allowed the thin, radial threads of the “firework” to remain intact and sharp for centuries, rather than being blurred away by cosmic winds.

A Brief Moment of Atomic Echoes

In seeking a way to describe this unique structure, the study authors looked back at a moment in human history when we created our own miniature stars. They compared the supernova’s morphology to the “Kingfish” high-altitude nuclear test explosion conducted by the United States in 1962. During the initial stages of that nuclear blast, similar filaments appeared, reaching out like glowing tentacles. However, in the Kingfish test, those filaments quickly dispersed, turning into a “cauliflower-like” shape within moments.

This comparison provides a vital clue to the life cycle of a supernova. Most typical, “homologous” explosions are far more powerful than the one that created Pa 30. They likely pass through a “firework” phase very similar to what we see in the 1181 remnant, but they do so in the blink of an eye. Because a standard supernova is so violent, the transition from sharp filaments to a messy, cauliflower-like cloud happens almost instantly.

The researchers explain, “This result suggests that homologous explosions (i.e., more typical supernovae) may pass through a morphological phase more similar to that of Pa 30, but with a temporal duration that is more short-lived than that of a wind-driven explosion.” Because the 1181 event was a “weak” explosion, the process was slowed down. The zombie star’s wind acted as a steady hand, preserving a stage of stellar death that is usually hidden by the sheer speed of total destruction.

Why the Frozen Fireworks Matter

This research is more than just an explanation for a beautiful image in a telescope; it is a fundamental shift in how we understand the death throes of stars. By matching the observed wind speed, density, and temperature of the filaments to their simulations, the team has proven that we are looking at a rare “unfinished” explosion.

As the study authors explain, “At a high level, our model suggests geometric, kinematic, and thermodynamic properties of the filaments that are consistent with observations. An important aspect of our model is that the dense wind of the natal WD remnant—not the preceding Type Iax supernova ejecta—primarily dictates the firework morphology of Pa 30, in line with radio upper limits that imply a weak explosion.”

Pa 30 acts as a cosmic magnifying glass, allowing us to see the intricate fluid dynamics that occur during a supernova in slow motion. It reveals that the shape of a star’s ghost is not just determined by the initial blast, but by the ongoing “breathing” of the survivor left behind. By studying this 850-year-old firework, astronomers are gaining a deeper understanding of the laws of physics that govern the most violent and beautiful events in the universe, proving that even a “failed” explosion can leave behind a masterpiece of scientific clarity.

More information: Eric R. Coughlin et al, A Wind-driven Origin for the Firework Morphology of the Supernova Remnant Pa 30, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae267d