Not far from our own corner of the Milky Way, something unseen may be quietly passing by. It leaves no light, no glow, no shadow against the stars. Yet its presence might have been betrayed by a subtle gravitational whisper, detected not through telescopes but through time itself. A group of US astronomers now suggests they may have found the first evidence of a dark matter sub-halo lurking just beyond our stellar neighborhood, close enough to tug gently on some of the most precise clocks in the universe.

The finding, reported in Physical Review Letters by a team led by Sukanya Chakrabarti at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, does not come with dramatic images or sudden flashes of discovery. Instead, it arrives through patience, precision, and a careful listening to the rhythm of distant stars. If confirmed, it could open a new way of uncovering how dark matter is arranged throughout our galaxy and bring astronomers one step closer to understanding the universe’s most dominant yet invisible substance.

The Invisible Architecture of the Cosmos

Dark matter has never been directly observed, yet its influence is written across the universe. Astronomers estimate that it makes up around 85% of the total mass of the universe, outweighing everything we can see, touch, or measure with light. According to the best cosmological models, this mysterious material does not drift aimlessly. Instead, it forms enormous, diffuse halos that envelop galaxies like the Milky Way, stretching far beyond their visible stars and gas.

Within these vast halos, theory predicts a rich inner structure. Smaller clumps, known as dark matter sub-halos, should be scattered throughout the galaxy. Some may carry masses exceeding tens of millions of times that of the sun, yet remain effectively invisible because they emit no light and interact only through gravity. Their gravitational pull on ordinary matter is expected to be faint, subtle enough to slip past most observational methods.

This creates a frustrating gap between theory and observation. Models say sub-halos should be common, but astronomers have struggled to find them. The universe seems to be hiding most of its mass in plain sight, daring scientists to find new ways of detecting what cannot be seen.

Pulsars and the Art of Listening to Time

To confront this challenge, Chakrabarti and her colleagues turned away from traditional searches for light and instead focused on timing. Their tools were pulsars, exotic remnants of massive stars that ended their lives in catastrophic explosions. These objects are highly magnetized, rapidly rotating neutron stars that emit powerful beams of electromagnetic radiation from their magnetic poles.

Because a pulsar’s magnetic axis is usually tilted relative to its rotation axis, those beams sweep across space like lighthouse beacons. When one of these beams crosses Earth, astronomers detect a pulse. The remarkable part is how consistent these pulses are. Some pulsars keep time with such reliability that they rival the best atomic clocks ever built by humans.

This regularity makes pulsars extraordinarily sensitive to motion. If a pulsar is accelerating toward or away from Earth, even slightly, the arrival times of its pulses shift. By measuring these shifts, astronomers can calculate the pulsar’s acceleration with astonishing precision. In essence, pulsars allow scientists to listen to the flow of time itself and notice when something unseen nudges it out of rhythm.

A Binary Star That Wouldn’t Stay in Line

In their study, the researchers focused on a rare and valuable target: a pulsar binary. This is a system in which a pulsar orbits a companion star, locked in a precise gravitational dance. Under normal circumstances, the timing of the pulsar’s pulses reveals a stable, predictable elliptical orbit, governed entirely by the mutual gravity of the two stars.

The team also examined nearby solitary pulsars to provide additional points of comparison. Together, these objects form a small but exquisitely sensitive network of clocks embedded in our galactic neighborhood.

When the researchers analyzed the timing data, something did not add up. The pulsars’ motions showed signs of being distorted, pulled slightly away from where they should have been if only the known stars were involved. The deviations were small, but persistent, and they carried a signature that suggested an external gravitational influence.

Time, it seemed, was being bent by something that refused to reveal itself.

Searching for a Visible Culprit

Before invoking dark matter, the team took a careful and conservative approach. They searched exhaustively for any ordinary objects that could explain the anomaly. A nearby star, a hidden gas cloud, or some other concentration of normal matter might have been responsible.

To do this, they turned to data from Gaia, the space mission mapping the positions and motions of stars with unprecedented accuracy. They also examined surveys of atomic and molecular hydrogen, looking for gas clouds dense enough to exert the required gravitational pull.

The search came up empty. No stars, no gas clouds, no conventional structures appeared capable of causing the observed distortions in the pulsars’ timing. The region of space seemed quiet and unremarkable, at least to every instrument designed to see ordinary matter.

With visible explanations ruled out, the researchers were left with the possibility that the source of the disturbance was invisible.

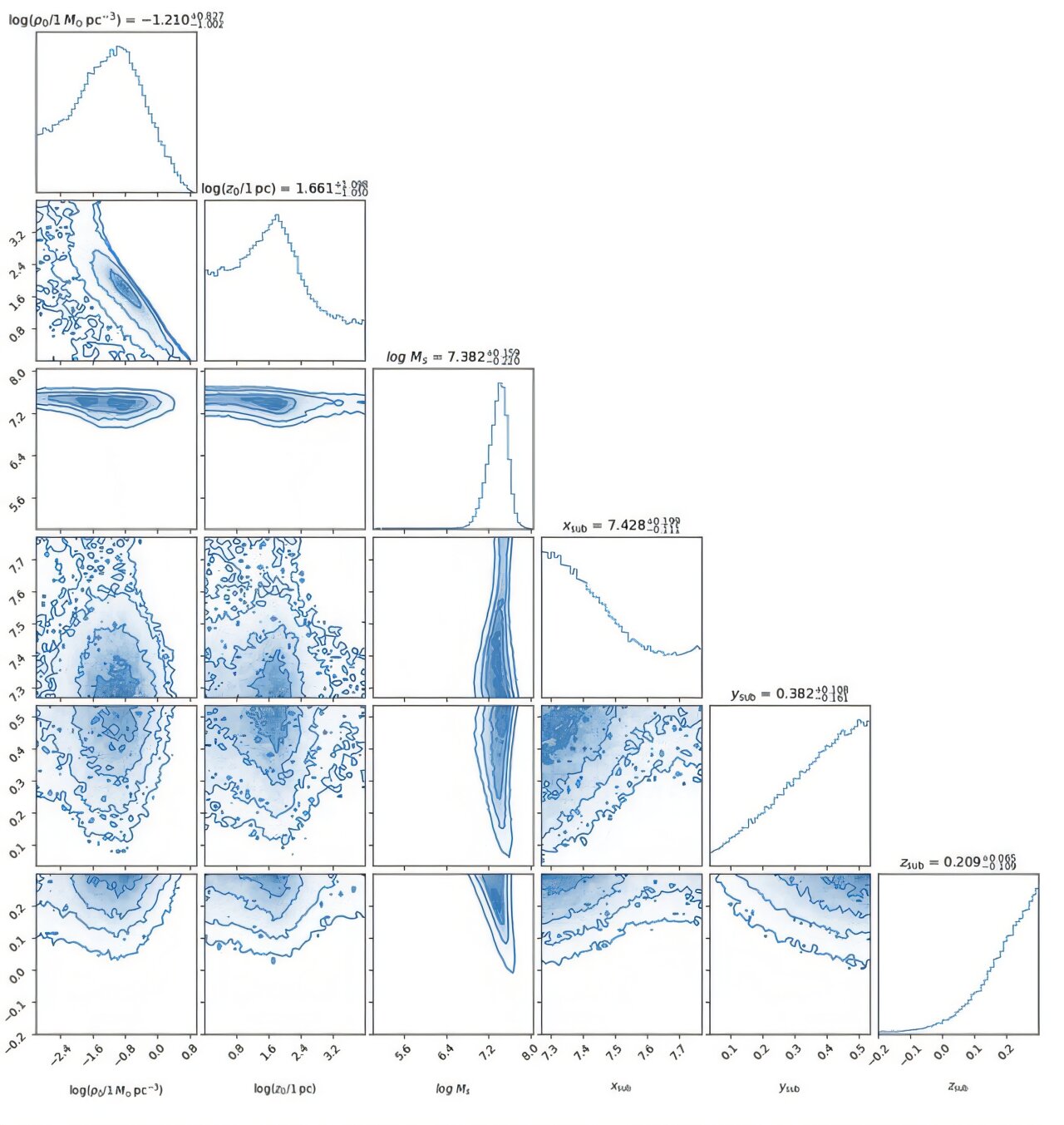

The Shape of an Unseen Neighbor

From the size of the timing distortions, the team inferred the mass of the unseen object responsible. Their calculations pointed to something weighing roughly tens of millions of solar masses. That number is far too large for a lone star or even a typical star cluster, yet entirely consistent with theoretical expectations for a dark matter sub-halo.

The inferred location made the finding even more intriguing. The object would lie just a few thousand light years from the sun, a relatively short distance on galactic scales. In the vastness of the Milky Way, this would place the sub-halo practically in our cosmic backyard.

If this interpretation is correct, it would represent the first evidence for such a structure detected through its gravitational influence on pulsars. Rather than seeing dark matter directly, astronomers would be mapping it through the way it quietly reshapes the motion of nearby stars, bending time just enough to be noticed by the universe’s most reliable clocks.

Doubt, Caution, and the Need for More Clocks

Despite the excitement, the researchers are careful not to overstate their claim. Significant uncertainty remains, and the team emphasizes that this signal alone cannot yet be considered definitive proof of a dark matter sub-halo. Pulsar binaries are rare objects, and conclusions drawn from a small sample must be treated with caution.

Independent lines of evidence will likely be needed before astronomers can say with confidence that a dark matter sub-halo has been found. Additional pulsar systems, improved timing data, or complementary methods of detection may help strengthen or challenge the interpretation.

Still, the study offers something valuable even in its uncertainty. It demonstrates a new and promising way to probe dark matter substructure, one that relies on precision timing rather than light. As more pulsars are studied with increasing accuracy, this approach could potentially be scaled up, allowing astronomers to map the hidden architecture of the Milky Way in unprecedented detail.

Why This Quiet Discovery Matters

This research matters because it points toward a future in which dark matter is no longer entirely beyond our observational reach. If pulsars can be used to detect dark matter sub-halos, astronomers may finally have a practical method for testing long-standing theoretical predictions about how dark matter is distributed throughout galaxies.

Understanding that distribution is essential for understanding how galaxies form, evolve, and hold themselves together. Dark matter shapes the cosmic scaffolding on which visible matter is built, yet its nature remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in physics.

By listening carefully to the ticking of distant stars, scientists are learning how to sense what cannot be seen. This possible nearby sub-halo, if confirmed, would not just be a new object added to a catalog. It would be a sign that the universe’s dominant form of matter is beginning to reveal itself, not through light, but through the gentle, persistent pull of gravity and the steady beat of cosmic time.

Study Details

Sukanya Chakrabarti et al, Constraints on a Dark Matter Subhalo Near the Sun from Pulsar Timing, Physical Review Letters (2026). DOI: 10.1103/29xz-nt5z