History often presents scientific progress as a neat sequence of hypotheses, experiments, and triumphs. In reality, many of the most transformative discoveries emerged not from carefully executed plans, but from mistakes, surprises, and moments of alert curiosity. Accidental discoveries are not the result of ignorance or carelessness; they occur when prepared minds recognize significance in the unexpected. As the scientist Louis Pasteur famously observed, chance favors only the prepared mind.

From life-saving medicines to technologies that reshaped civilization, accidental discoveries reveal a profound truth about science: progress is not only driven by intention, but also by openness to the unforeseen. The following seven examples demonstrate how chance encounters, laboratory mishaps, and unintended results changed the course of human history, not because they were accidents alone, but because someone noticed, questioned, and understood what others might have ignored.

1. Penicillin: The Mold That Became Medicine

In 1928, Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned to his laboratory after a vacation to find something unusual. Several petri dishes containing cultures of Staphylococcus bacteria had been contaminated with mold. In most laboratories, such contamination would have meant immediate disposal. Fleming, however, noticed something striking: around the mold colonies, the bacteria had been destroyed.

The mold was later identified as Penicillium notatum. Fleming realized that this organism was producing a substance capable of killing bacteria without harming human cells. He named the substance penicillin. At the time, Fleming struggled to isolate and purify it, and his discovery initially attracted limited attention. It would take more than a decade before other scientists developed methods to mass-produce penicillin for medical use.

Once that happened, the impact was revolutionary. Penicillin became the first true antibiotic, transforming medicine almost overnight. Infections that had once been fatal—such as pneumonia, sepsis, and wound infections—became treatable. During World War II, penicillin saved countless lives by preventing deaths from infected injuries.

What makes penicillin especially remarkable is not only its effectiveness, but the way it reframed medicine. It ushered in the antibiotic era, changing how doctors approached disease and surgery. All of this stemmed from a forgotten petri dish and a scientist curious enough to ask why bacteria were dying around a patch of mold.

2. X-Rays: Seeing the Invisible

In 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was experimenting with cathode ray tubes, devices used to study electrical discharge in gases. While working in a darkened room, Röntgen noticed that a fluorescent screen across the room began to glow whenever the tube was activated, even though it was shielded from visible light.

This unexpected glow suggested the presence of an unknown form of radiation capable of passing through solid objects. Röntgen called these mysterious emissions “X-rays,” using “X” to denote their unknown nature. Further experiments revealed that X-rays could pass through soft tissues while being absorbed by denser materials such as bone.

Within weeks, Röntgen produced the first X-ray image of a human body: a haunting photograph of his wife’s hand, clearly showing her bones and wedding ring. The scientific and public response was immediate and intense. For the first time in history, humans could see inside the living body without surgery.

X-rays transformed medicine, enabling accurate diagnosis of fractures, tumors, and internal injuries. They also revolutionized physics by revealing new properties of electromagnetic radiation. Over time, X-ray technology expanded into fields ranging from astronomy to airport security.

This discovery was not the result of a search for medical imaging, but of a physicist paying attention to an anomaly. Röntgen’s willingness to investigate an unexpected glow opened an entirely new window into the hidden structures of nature.

3. The Microwave Oven: A Melted Chocolate Bar

During the 1940s, American engineer Percy Spencer was working on radar technology for military applications. While testing a magnetron—a device that generates microwaves—Spencer noticed something odd. A chocolate bar in his pocket had melted, even though the room temperature was normal.

Intrigued, Spencer conducted further experiments. He placed popcorn kernels near the magnetron, which promptly popped. An egg exposed to the microwaves exploded. These curious results revealed that microwaves could rapidly heat food by exciting water molecules, causing them to vibrate and produce heat.

This accidental observation led to the invention of the microwave oven. Early models were large, expensive, and primarily used in industrial or commercial settings. Over time, advances in engineering made microwave ovens smaller, safer, and affordable for households.

The microwave oven changed daily life in subtle but profound ways. It altered cooking habits, reshaped food industries, and transformed how people manage time in modern households. Meals that once required long preparation could be heated in minutes.

The scientific principle behind microwave heating is straightforward, but its application emerged from chance. A melted chocolate bar, noticed by a curious engineer, reshaped kitchens around the world.

4. Vulcanized Rubber: A Burnt Experiment That Bounced Back

In the early nineteenth century, rubber was a problematic material. Natural rubber became sticky in heat and brittle in cold, limiting its practical use. American inventor Charles Goodyear spent years obsessively experimenting with rubber, often facing financial ruin.

In 1839, Goodyear accidentally dropped a mixture of rubber and sulfur onto a hot stove. Instead of melting into a useless mess, the rubber charred slightly but retained its elasticity and strength. Unlike untreated rubber, it did not become sticky when heated or crack when cooled.

This accident led to the process known as vulcanization, in which rubber is heated with sulfur to create strong chemical cross-links between polymer chains. Vulcanized rubber is durable, flexible, and resistant to temperature changes.

The impact of vulcanized rubber was enormous. It made possible reliable tires, industrial belts, seals, and countless other products essential to modern transportation and manufacturing. The automotive revolution would have been impossible without it.

Goodyear’s discovery highlights the emotional dimension of accidental science. His persistence and deep familiarity with his material allowed him to recognize success where others might have seen failure. A burnt experiment became the foundation of a global industry.

5. Radioactivity: An Unexpected Glow in the Dark

In 1896, French physicist Henri Becquerel was investigating the properties of phosphorescent materials. He hypothesized that certain substances might emit X-rays after exposure to sunlight. To test this, he wrapped photographic plates in black paper and placed uranium salts on top, intending to expose them to sunlight.

When cloudy weather prevented sunlight exposure, Becquerel postponed the experiment and stored the plates in a drawer. Later, he developed the plates anyway and was astonished to find clear images on them. The uranium salts had emitted radiation without any external energy source.

This observation marked the discovery of radioactivity, a phenomenon in which unstable atomic nuclei spontaneously release energy. Becquerel’s work was soon expanded by Marie and Pierre Curie, who identified new radioactive elements and explored their properties.

Radioactivity revolutionized physics by revealing that atoms were not indivisible, as previously believed. It led to the development of nuclear physics, radiometric dating, and nuclear medicine. At the same time, it raised ethical and safety concerns, particularly with the later development of nuclear weapons.

The discovery of radioactivity emerged from an experiment that did not go as planned. Becquerel’s decision to investigate an unexpected result revealed a hidden source of energy within matter itself.

6. Teflon: A Missing Gas with Remarkable Properties

In 1938, chemist Roy Plunkett was working with gases related to refrigeration technology. While experimenting with tetrafluoroethylene gas stored in pressurized cylinders, Plunkett discovered that one cylinder appeared empty, despite weighing the same as before.

Upon opening the cylinder, he found a white, waxy solid coating the interior. The gas had polymerized unexpectedly, forming a new substance. This material, later named polytetrafluoroethylene and marketed as Teflon, exhibited remarkable properties.

Teflon was chemically inert, resistant to heat, and had an extremely low coefficient of friction. Initially, its applications were limited to specialized industrial uses, including seals and coatings in chemical equipment. Over time, its non-stick properties found widespread use in cookware.

Beyond the kitchen, Teflon became essential in aerospace engineering, electronics, and medical devices. Its resistance to chemical reactions and high temperatures made it invaluable in environments where few materials could survive.

This discovery illustrates how accidents can reveal materials with properties no one was actively seeking. A missing gas led to a substance that quietly became embedded in everyday life.

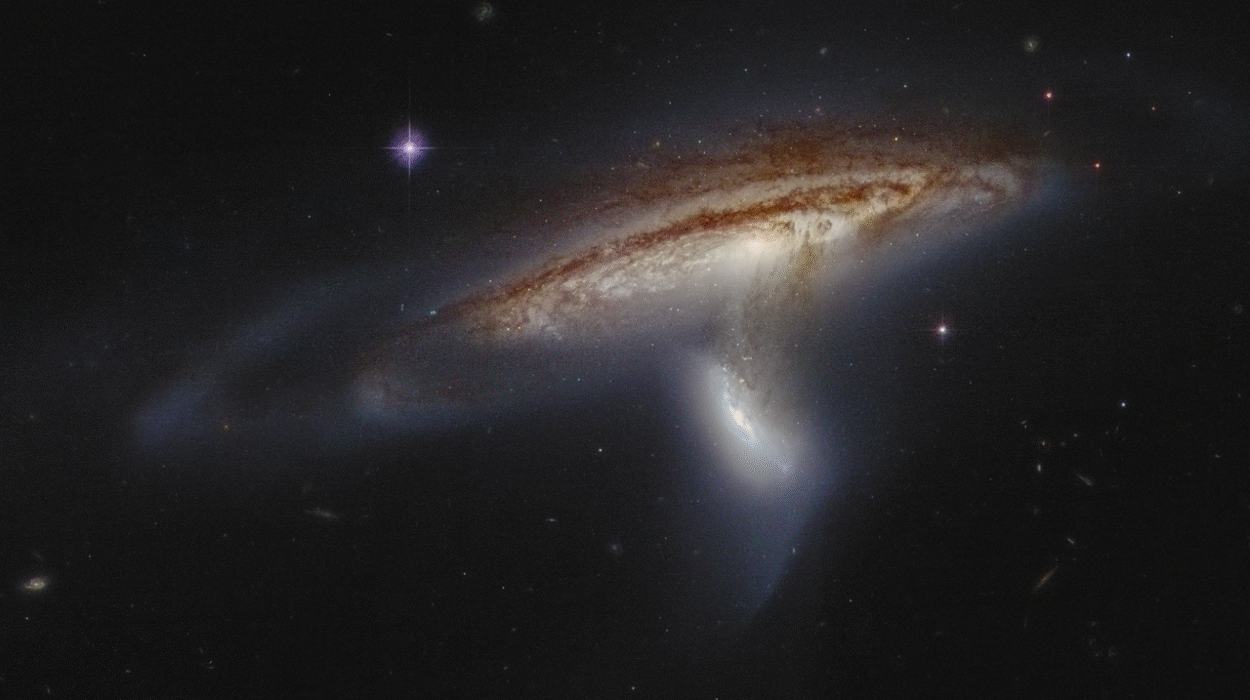

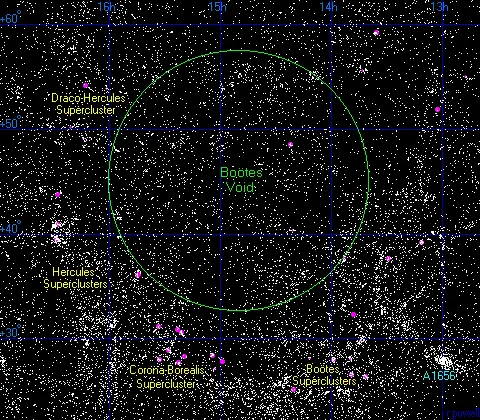

7. The Discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background: Noise That Wasn’t Noise

In the 1960s, radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were working with a sensitive microwave antenna in New Jersey. They encountered a persistent background noise that interfered with their measurements. No matter where they pointed the antenna, the noise remained constant.

The researchers meticulously checked every possible source of interference. They removed electronic equipment, recalibrated instruments, and even cleaned out pigeon droppings from the antenna. The noise persisted.

Unbeknownst to them, theoretical physicists had predicted the existence of faint microwave radiation left over from the early universe—a remnant of the Big Bang itself. When Penzias and Wilson learned of this prediction, they realized that the noise they were detecting was not a problem, but a profound signal.

The cosmic microwave background radiation provided strong evidence for the Big Bang theory, reshaping cosmology and our understanding of the universe’s origin. It revealed that the universe began in a hot, dense state and has been expanding ever since.

This accidental discovery transformed astronomy into a precision science and earned Penzias and Wilson the Nobel Prize. What began as an annoying technical problem became one of the most important observations in modern physics.

Conclusion: When Chance Meets Curiosity

Accidental discoveries do not diminish the role of scientific rigor; they highlight it. In every case described here, chance presented an anomaly, but understanding emerged only because someone recognized its importance and pursued it with care and insight.

These discoveries remind us that science is not a rigid path but an evolving dialogue between expectation and reality. Errors, surprises, and unintended results are not obstacles to progress—they are often its engine. What matters is the willingness to ask why something unexpected occurred.

From a moldy petri dish to cosmic radiation echoing from the birth of the universe, accidental discoveries have saved lives, transformed technology, and reshaped our understanding of reality. They stand as enduring evidence that curiosity, patience, and openness to the unexpected can change the course of history.