The question of whether Earth is unique has haunted human thought for centuries. Once confined to philosophy and imagination, this question has now become a central scientific pursuit. Over the past three decades, astronomers have confirmed the existence of thousands of planets orbiting stars beyond our Sun, known as exoplanets. Among this astonishing diversity of worlds, a small but deeply compelling group stands out: Earth-like exoplanets. These are worlds that, based on current evidence, resemble Earth in size, composition, temperature, or potential habitability.

An Earth-like exoplanet does not need to be an exact replica of our planet. Instead, scientists look for several converging characteristics. These include a rocky composition, a size comparable to Earth, and an orbit within the “habitable zone” of its star, where liquid water could exist on the surface under suitable atmospheric conditions. Additional factors, such as stellar activity, planetary density, and orbital stability, further refine assessments of habitability.

This article explores the top ten Earth-like exoplanets discovered so far, based on scientific consensus, observational data, and habitability metrics. Each of these worlds represents a milestone in our growing understanding of planetary systems and brings us closer to answering one of humanity’s most profound questions: are we alone in the universe?

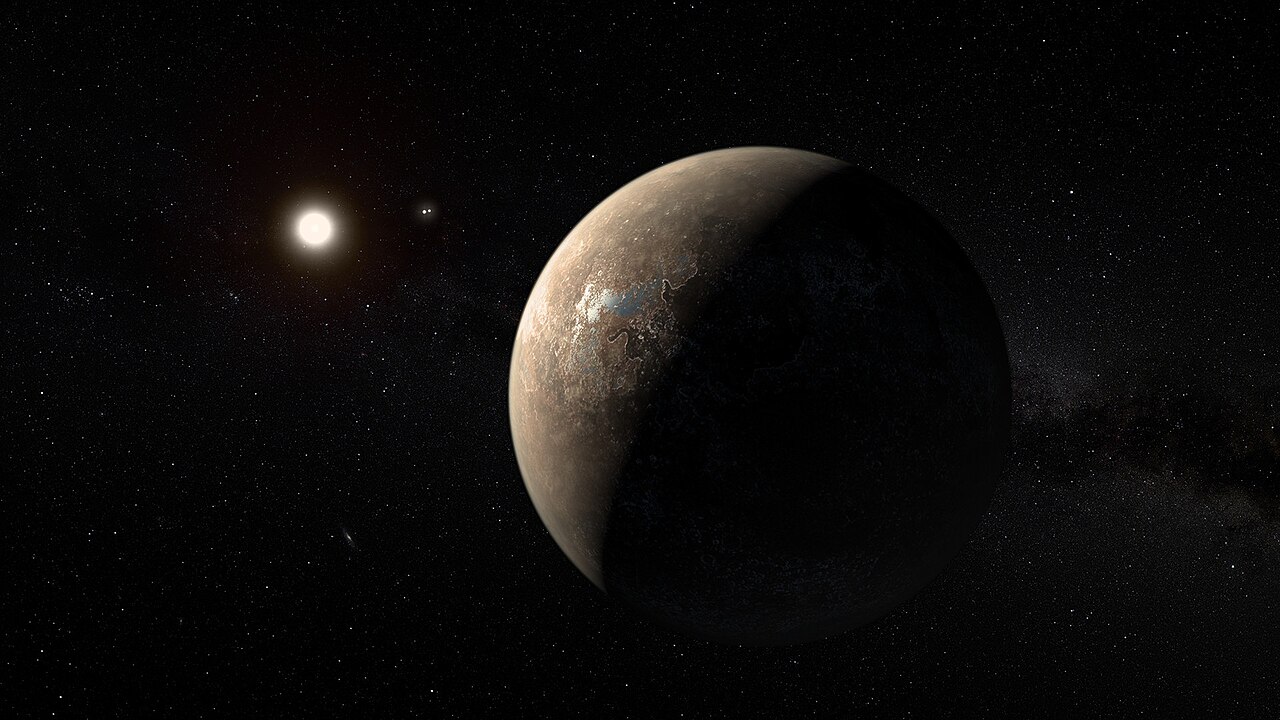

1. Proxima Centauri b

Proxima Centauri b is often regarded as the most tantalizing Earth-like exoplanet discovered to date, largely because of its proximity. Orbiting Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun at just over four light-years away, this planet has reshaped how scientists think about nearby stellar systems. Discovered in 2016 using the radial velocity method, Proxima Centauri b has a minimum mass about 1.17 times that of Earth, placing it firmly in the category of rocky planets.

The planet orbits within the habitable zone of its red dwarf star, completing one revolution every 11.2 Earth days. Because red dwarfs are cooler and dimmer than the Sun, their habitable zones lie much closer to the star. This proximity raises concerns about tidal locking, where one side of the planet permanently faces the star while the other remains in darkness. However, climate models suggest that with a sufficiently thick atmosphere, heat could be redistributed across the planet, potentially allowing liquid water to exist.

One major challenge to Proxima Centauri b’s habitability is stellar activity. Proxima Centauri is a flare star, capable of emitting powerful bursts of radiation that could erode planetary atmospheres. Despite this, the planet remains a prime target for future telescopes and even conceptual interstellar missions, making it a cornerstone of exoplanet science.

2. TRAPPIST-1e

Among all known exoplanetary systems, TRAPPIST-1 holds a special place. This ultra-cool red dwarf star hosts seven Earth-sized planets, three of which orbit within the habitable zone. Of these, TRAPPIST-1e is widely considered the most Earth-like.

TRAPPIST-1e has a radius and mass remarkably similar to Earth, resulting in a comparable density that strongly suggests a rocky composition. It orbits its star every six Earth days and receives a level of stellar radiation similar to what Earth receives from the Sun. Climate simulations indicate that, under a range of plausible atmospheric compositions, TRAPPIST-1e could maintain surface temperatures compatible with liquid water.

Importantly, observations from space-based telescopes have constrained the likelihood of a thick hydrogen-dominated atmosphere, increasing the plausibility of an Earth-like atmosphere instead. While stellar flares remain a concern, TRAPPIST-1e stands as one of the strongest candidates for habitability discovered so far.

3. Kepler-452b

Kepler-452b is often described as Earth’s “older cousin,” and for good reason. Discovered by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope in 2015, this planet orbits a Sun-like star approximately 1,400 light-years away. Its orbital period of 385 Earth days is strikingly similar to Earth’s year, placing it squarely within the habitable zone of its star.

Kepler-452b has a radius about 1.6 times that of Earth, suggesting it may be a super-Earth. While this size raises the possibility of a thicker atmosphere or stronger gravity, models indicate that planets of this size can still be rocky. Its host star is older than the Sun, implying that Kepler-452b has had billions of years for potential biological processes to develop, assuming suitable conditions.

The combination of a Sun-like star, Earth-like orbital distance, and long-term stability makes Kepler-452b one of the most compelling Earth analog candidates discovered during the Kepler mission.

4. Kepler-186f

Kepler-186f marked a historic moment in exoplanet research when it was announced in 2014 as the first Earth-sized planet found within the habitable zone of another star. Orbiting a red dwarf star about 500 light-years away, Kepler-186f has a radius just 10 percent larger than Earth.

The planet receives about one-third of the stellar energy that Earth receives from the Sun, placing it near the outer edge of its star’s habitable zone. This suggests that Kepler-186f could be colder than Earth, but a sufficiently strong greenhouse effect could allow liquid water to persist. Its longer orbital period of 130 Earth days and Earth-like size have made it a benchmark for habitable-zone discoveries.

Although its distance makes detailed atmospheric characterization challenging with current technology, Kepler-186f remains a foundational example of how common potentially habitable planets may be in the galaxy.

5. TOI-700 d

TOI-700 d is a relatively recent addition to the catalog of Earth-like exoplanets and represents a major success for NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). Discovered in 2020, this planet orbits a quiet red dwarf star approximately 100 light-years away.

With a radius close to Earth’s and an orbital period of 37 days, TOI-700 d lies firmly within its star’s habitable zone. Its host star is notably less active than many red dwarfs, reducing concerns about atmospheric erosion from stellar flares. Climate modeling studies suggest that TOI-700 d could support surface liquid water under a variety of atmospheric scenarios.

Because of its relative proximity and favorable stellar environment, TOI-700 d is considered one of the best targets for atmospheric study with next-generation space telescopes.

6. LHS 1140 b

LHS 1140 b is a super-Earth orbiting a red dwarf star about 40 light-years away. Discovered in 2017, it has a mass approximately 6.6 times that of Earth and a radius about 1.7 times larger, resulting in a high density that strongly indicates a rocky composition.

The planet orbits within the habitable zone and receives a moderate amount of stellar radiation. Notably, LHS 1140 b’s large mass may have helped it retain a thick atmosphere despite early stellar activity, potentially protecting surface conditions conducive to liquid water. Its slow orbital motion and stable star make it an excellent candidate for atmospheric characterization.

LHS 1140 b illustrates how planets somewhat larger than Earth may still be promising candidates for habitability, expanding the traditional definition of Earth-like worlds.

7. Kepler-62f

Kepler-62f is part of a five-planet system orbiting a star smaller and cooler than the Sun, located about 1,200 light-years away. This planet has a radius approximately 1.4 times that of Earth and orbits within the outer region of the habitable zone.

Although Kepler-62f likely receives less stellar energy than Earth, climate models suggest that with sufficient greenhouse gases, it could maintain liquid water on its surface. Its relatively low stellar irradiation may even help stabilize long-term climate conditions, provided an appropriate atmosphere exists.

Kepler-62f demonstrates the diversity of potentially habitable environments and highlights the role of atmospheric composition in determining planetary habitability.

8. Ross 128 b

Ross 128 b orbits a nearby red dwarf star just 11 light-years away, making it one of the closest Earth-mass exoplanets known. Discovered in 2017, it has a minimum mass about 1.35 times that of Earth and orbits near the inner edge of the habitable zone.

Crucially, Ross 128 is a relatively quiet star, emitting far fewer flares than many red dwarfs. This increases the likelihood that Ross 128 b could retain an atmosphere over long periods. While it may be slightly warmer than Earth, moderate atmospheric conditions could still permit surface liquid water.

Its proximity makes Ross 128 b a prime candidate for future direct observation and atmospheric analysis.

9. Gliese 667 Cc

Gliese 667 Cc orbits a red dwarf star within a triple-star system about 23 light-years away. With a minimum mass roughly 3.8 times that of Earth, it is classified as a super-Earth. The planet receives a similar amount of stellar energy to Earth and resides well within the habitable zone.

Despite its larger mass, models suggest that Gliese 667 Cc could be rocky and capable of supporting liquid water. The star’s relatively low luminosity and long-term stability further enhance its habitability prospects.

This planet was one of the earliest examples to demonstrate that potentially habitable worlds may be common around red dwarf stars.

10. Kepler-1649c

Kepler-1649c is often described as one of the closest Earth analogs in terms of size and stellar energy received. Discovered through reanalysis of Kepler data in 2020, it orbits a red dwarf star about 300 light-years away.

The planet has a radius only 6 percent larger than Earth and receives approximately 75 percent of the energy Earth receives from the Sun. Its orbital period of 19.5 days places it comfortably within the habitable zone. These characteristics make Kepler-1649c one of the most Earth-like planets known in terms of physical parameters.

Although its star is a red dwarf, the planet’s striking similarities to Earth underscore the potential abundance of Earth-sized habitable-zone planets in the Milky Way.

The Scientific Meaning of “Earth-Like”

It is essential to understand that “Earth-like” does not mean “Earth-identical.” None of the exoplanets described here are known to have oceans, continents, or life. Rather, they share key measurable properties with Earth that make them promising candidates for habitability. Factors such as atmospheric composition, magnetic fields, and geological activity remain largely unknown for these distant worlds.

The classification of Earth-like exoplanets is therefore probabilistic, grounded in physics, planetary science, and climate modeling. As observational techniques improve, many of these assessments may be refined or revised.

Why Earth-Like Exoplanets Matter

The discovery of Earth-like exoplanets has transformed our understanding of the universe. It suggests that the conditions required for potentially habitable worlds are not rare or unique. Instead, they may be a natural outcome of planet formation around many types of stars.

These discoveries also have profound philosophical implications. They challenge the idea of Earth’s uniqueness and invite new perspectives on life, biology, and humanity’s place in the cosmos. Scientifically, they guide the design of future missions aimed at detecting biosignatures, such as atmospheric oxygen or methane, that could indicate biological activity.

The Road Ahead

The coming decades promise a revolution in the study of Earth-like exoplanets. Advanced space telescopes and ground-based observatories will enable detailed atmospheric analysis, surface characterization, and even the search for indirect signs of life. As data accumulates, some of the planets listed here may move closer to or farther from the category of true Earth analogs.

What remains certain is that the discovery of Earth-like exoplanets marks one of the most significant achievements in the history of science. Each new world expands the boundaries of human knowledge and brings us closer to understanding whether life is a cosmic rarity or a universal phenomenon.

In searching the stars for reflections of our own world, we are not merely cataloging distant planets. We are continuing an ancient human story, driven by curiosity, wonder, and the enduring desire to know whether, somewhere in the vastness of space, another Earth may be looking back.