In the deep silence of space, long after a star has exhausted its brilliance, a small, dense ember remains. It does not burn. It does not roar with nuclear fire. It simply exists—hot at first, then slowly cooling over billions of years, fading toward darkness. This stellar remnant is known as a white dwarf, and it represents the final, inevitable fate of stars like our Sun. White dwarfs are not dramatic explosions or cosmic catastrophes. Instead, they are quiet endings, carrying within them the memory of a star’s entire life.

To understand white dwarfs is to understand time on a cosmic scale. These objects are ancient archives of stellar history, compressed into bodies no larger than a planet yet containing nearly the mass of a star. They are at once simple and profoundly strange, governed by the deepest laws of physics and standing at the boundary between familiar matter and the exotic states found nowhere on Earth.

The Life of a Sun-Like Star Before the End

Every white dwarf begins its story as a normal star. Stars like our Sun are born from vast clouds of gas and dust, collapsing under gravity until their cores become hot and dense enough to ignite nuclear fusion. For most of their lives, these stars exist in a stable balance. Gravity pulls inward, while energy from fusion pushes outward. Hydrogen is fused into helium in the core, releasing light and heat that can shine steadily for billions of years.

This long, stable phase is where stars spend most of their existence. It is also the phase that makes life possible around stars like the Sun. The gentle, reliable energy output creates a cosmic calm, allowing planets to form and evolve. But this balance cannot last forever. Hydrogen, the fuel of stellar youth, is finite.

As the hydrogen in the core is depleted, the star begins to change. Fusion shifts outward into a shell surrounding the core, and the star expands dramatically into a red giant. Its outer layers swell and cool, while the core contracts and heats up. For a time, helium fusion may ignite, producing heavier elements such as carbon and oxygen. But stars like the Sun are not massive enough to continue this process indefinitely. They cannot generate the temperatures and pressures required to fuse elements beyond this stage.

Eventually, fusion ceases. The star has reached the end of its ability to produce energy through nuclear reactions. What remains is the core—hot, dense, and exposed as the outer layers drift away into space, forming a glowing planetary nebula. At the center of this expanding cloud sits the white dwarf, the naked core of a once-living star.

Birth of a White Dwarf

The formation of a white dwarf is not violent like a supernova. It is a gentle cosmic shedding. The star’s outer layers are lost gradually, carried away by stellar winds and pulses of expansion. These layers glow briefly as they are illuminated by the intense ultraviolet radiation from the exposed core, creating some of the most beautiful structures in the universe.

Once the surrounding gas disperses, the white dwarf is left alone. It is no longer generating energy. There is no fusion, no internal source of heat. What remains is residual thermal energy from its former life. This heat slowly leaks away into space over immense spans of time.

At birth, a white dwarf is extremely hot, with surface temperatures far exceeding those of ordinary stars. But despite this heat, it is faint. Its small size limits how much light it can emit. Over time, it cools, dims, and reddens, beginning a slow journey toward darkness that may last longer than the current age of the universe.

Size, Mass, and Extreme Density

One of the most astonishing aspects of white dwarfs is their density. A white dwarf typically has a mass comparable to that of the Sun, yet it is packed into a volume similar to that of Earth. This means that its average density is millions of times greater than anything found on our planet.

To imagine this density, consider that a teaspoon of white dwarf material would weigh as much as a large mountain. At such extreme densities, atoms are crushed together. Electrons are forced into states that would be impossible under ordinary conditions. Matter behaves in ways that defy everyday intuition.

This compression is not unlimited. There is a maximum mass a white dwarf can have, beyond which it cannot support itself against gravity. This limit arises from a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics and plays a crucial role in the evolution of stars and the most powerful explosions in the universe.

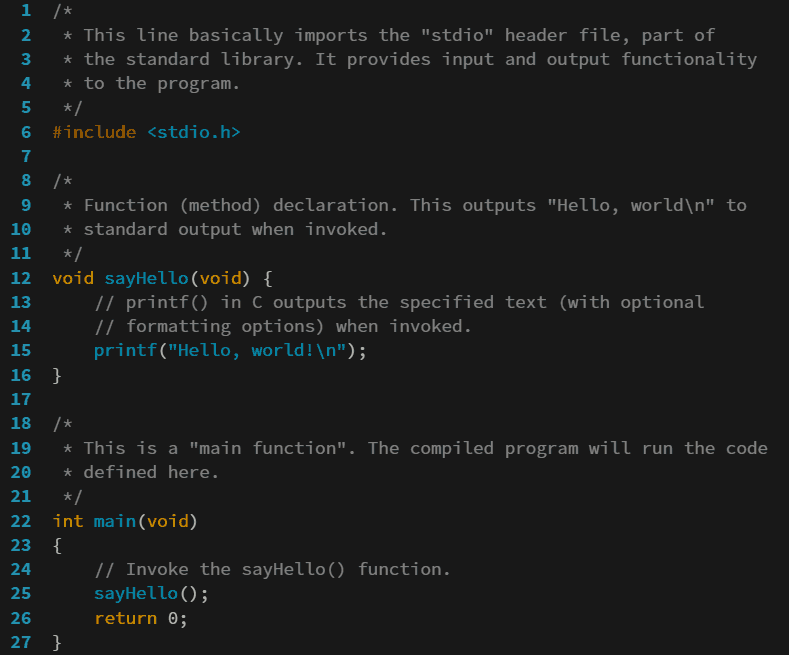

Electron Degeneracy Pressure: The Physics That Holds a White Dwarf Together

A white dwarf does not resist gravity through heat generated by fusion. Instead, it is supported by a quantum mechanical effect known as electron degeneracy pressure. According to the laws of quantum physics, electrons cannot occupy the same quantum state. When matter is compressed to extreme densities, electrons are forced into higher and higher energy states, creating a pressure that resists further compression.

This pressure does not depend on temperature. Even as a white dwarf cools, electron degeneracy pressure remains. This is why white dwarfs can exist as stable objects long after they stop producing energy. Gravity pulls inward, electrons push back, and a new equilibrium is achieved.

This balance is delicate. If a white dwarf gains too much mass, gravity can overwhelm electron degeneracy pressure. When that happens, the consequences are catastrophic, leading to phenomena that reshape galaxies and seed the universe with heavy elements.

Composition of White Dwarfs

Most white dwarfs are composed primarily of carbon and oxygen, the ashes of helium fusion in their progenitor stars. These elements form a dense, crystalline lattice deep within the white dwarf’s interior. In some cases, especially for lower-mass stars, white dwarfs may be rich in helium. In others, more massive progenitors can produce white dwarfs with cores dominated by oxygen and neon.

The outermost layer of a white dwarf is usually a thin atmosphere of hydrogen or helium. This atmosphere, though incredibly shallow compared to the star’s overall mass, determines how the white dwarf appears to observers. Its composition influences the spectrum of light emitted and provides clues about the star’s history.

Over time, gravity causes heavier elements to sink toward the interior, leaving the lightest elements at the surface. This process creates a chemically pure exterior, making white dwarfs some of the simplest stars to model, despite the exotic physics governing their interiors.

Cooling: A Cosmic Clock

White dwarfs shine not because they generate energy, but because they are hot. As they radiate energy into space, they cool gradually. This cooling process is extremely slow, taking billions of years. The rate at which a white dwarf cools depends on its mass, composition, and internal structure.

Because the cooling is predictable, white dwarfs serve as cosmic clocks. By observing the temperatures and luminosities of white dwarfs in star clusters or the Milky Way, astronomers can estimate the ages of these systems. In some cases, white dwarfs provide the most reliable age measurements available, offering insight into the history of our galaxy.

As a white dwarf cools further, it undergoes a remarkable transformation. The ions in its interior begin to arrange themselves into an ordered, crystalline structure. In effect, the core of the white dwarf becomes a giant cosmic crystal, slowly solidifying over time.

Crystallization: When Stars Become Solid

The idea that a star can crystallize sounds like science fiction, yet it is a real and well-understood phenomenon in white dwarfs. As the interior cools, thermal motion decreases. Eventually, the ions settle into a lattice, similar to the structure of a solid crystal.

This crystallization releases latent heat, temporarily slowing the cooling process. As a result, white dwarfs can linger at certain temperatures longer than expected. Observations of white dwarf populations have provided evidence for this process, confirming predictions made decades earlier.

The crystallized core of a white dwarf is unlike any solid found on Earth. It exists under pressures so immense that ordinary concepts of solidity lose their meaning. Yet this phase transition is a profound reminder that even stars are subject to the same physical principles that govern matter everywhere.

Binary Systems and the Danger of Mass Transfer

Many stars exist in binary systems, orbiting a companion. If a white dwarf has a nearby partner, its quiet fate can be dramatically altered. Matter from the companion star can be pulled onto the white dwarf’s surface, increasing its mass.

As material accumulates, pressure and temperature rise. Under the right conditions, this can trigger explosive events. In some cases, hydrogen accreted onto the surface ignites in a thermonuclear flash, producing a nova. These outbursts can recur multiple times, making the system periodically bright.

If the white dwarf continues to gain mass and approaches the critical limit where electron degeneracy pressure fails, the result can be a Type Ia supernova. In this event, the white dwarf is completely destroyed in a thermonuclear explosion, briefly shining brighter than an entire galaxy.

White Dwarfs and Cosmic Explosions

Type Ia supernovae are among the most important phenomena in astronomy. Because they occur when white dwarfs reach a consistent mass threshold, their brightness is remarkably uniform. This makes them valuable tools for measuring cosmic distances and studying the expansion of the universe.

These explosions play a crucial role in cosmic evolution. They forge and disperse heavy elements such as iron, enriching the interstellar medium. The atoms in our blood and bones owe their existence, in part, to the violent deaths of white dwarfs in distant galaxies.

Thus, while white dwarfs themselves are quiet, their ultimate fate in certain systems can influence the universe on the largest scales.

White Dwarfs in the Milky Way

Our galaxy contains billions of white dwarfs. Many are ancient, remnants of stars that formed early in the Milky Way’s history. Some are so cool and faint that they are difficult to detect, blending into the dark background of space.

Studying these objects provides insight into the galaxy’s past. The distribution, temperatures, and motions of white dwarfs reveal information about star formation rates, chemical evolution, and the age of different galactic components.

The Sun itself is destined to become one of these objects. In about five billion years, it will shed its outer layers and leave behind a white dwarf roughly the size of Earth. Long after Earth is gone, the Sun’s remnant will persist, cooling quietly in the darkness.

White Dwarfs and the Fate of the Universe

White dwarfs are among the longest-lasting stellar objects in the universe. While massive stars burn out quickly and neutron stars and black holes form under extreme conditions, white dwarfs endure. Their slow cooling means they will remain detectable long after other stars have faded.

In the unimaginably distant future, when star formation has ceased and galaxies have grown dark, white dwarfs will dominate the stellar population. Eventually, after trillions of years, they too will cool into black dwarfs—objects so cold that they emit no detectable light. Though none exist yet, the concept highlights the ultimate fate of stellar matter.

White dwarfs thus connect the present universe to its far future, acting as bridges across time.

Why White Dwarfs Matter

White dwarfs may seem like endings, but they are also beginnings. They influence galactic chemistry, power cosmic explosions, and provide tools for measuring time and distance. They challenge our understanding of matter under extreme conditions and test the limits of physical theory.

Emotionally, white dwarfs tell a quiet, poignant story. They are the final state of stars that once shone brightly, warmed planets, and perhaps hosted life. They remind us that even the most stable and life-giving objects are temporary, subject to change and decay.

Yet there is beauty in this ending. A white dwarf is not chaos, but order. It is a star that has found a new balance, governed by the deepest rules of nature. In its slow cooling and crystallization, it embodies patience on a cosmic scale.

To look at a white dwarf is to look at the future of our Sun and, in a sense, the future of all things. It is a reminder that the universe is both fleeting and enduring, filled with dramatic explosions and silent remnants, all bound together by the same laws.

White dwarfs are not merely stellar corpses. They are monuments to the life cycles of stars, silent witnesses to cosmic history, and crystalline echoes of suns that once burned with light.