Lightning is one of nature’s most dramatic contradictions. It is brief yet powerful, familiar yet deeply mysterious. For thousands of years, humans have watched lightning tear open the sky, split trees, ignite fires, and strike fear into entire civilizations. We have learned to harness electricity, send spacecraft beyond the solar system, and probe the fabric of spacetime—yet when a thunderstorm forms overhead, we still cannot say with certainty where the next lightning bolt will strike.

This failure is not due to lack of effort or intelligence. It is because lightning sits at the intersection of chaos, complexity, and extreme physics. It emerges from a turbulent atmosphere, involves processes unfolding faster than human perception, and depends on invisible structures we are only beginning to measure. Lightning is not just a spark; it is a violent negotiation between cloud and ground, guided by chance, structure, and instability.

To understand why lightning remains so difficult to predict, we must journey into the physics of storms, electric fields, charged particles, and the limits of measurement itself.

The Ancient Fear and Modern Curiosity of Lightning

Long before science, lightning shaped human imagination. Ancient cultures saw it as divine judgment or cosmic warfare. Gods hurled lightning bolts as weapons; thunder was the voice of power. Even today, despite our scientific explanations, lightning retains an emotional grip. The sudden flash, the explosive sound, the raw display of energy tap into something primal.

Modern physics has stripped lightning of its supernatural status, but not its awe. A single lightning strike can heat air hotter than the surface of the Sun, carry hundreds of millions of volts, and release energy equivalent to large amounts of explosive force. Yet this violence unfolds in fractions of a second, within a chaotic environment we struggle to map.

Lightning reminds us that nature does not always cooperate with our desire for control. It reveals the limits of prediction, even in an age of satellites, supercomputers, and advanced sensors.

How Thunderstorms Become Electrically Alive

Lightning begins long before the first flash appears. Its story starts inside towering thunderclouds, especially cumulonimbus clouds that can stretch tens of kilometers into the sky. These clouds are not static objects but turbulent systems driven by heat, moisture, and gravity.

Warm, moist air rises from the ground, cooling as it ascends. Water vapor condenses into droplets, releases latent heat, and fuels further upward motion. As air continues to rise, temperatures drop low enough for ice crystals, supercooled water droplets, and soft hail known as graupel to coexist.

The crucial physics of lightning begins here, in the chaotic collisions between these particles. When ice crystals and graupel collide under specific conditions of temperature and motion, electric charge is transferred. Typically, graupel becomes negatively charged and falls, while lighter ice crystals gain positive charge and are carried upward by strong updrafts.

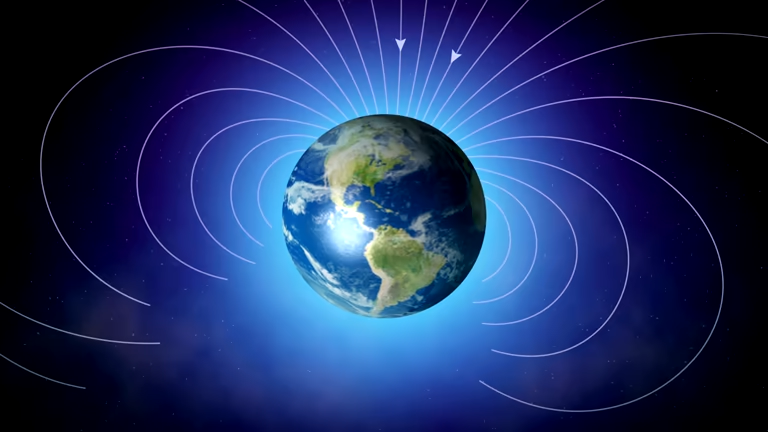

Over time, the cloud becomes electrically stratified. Positive charge accumulates near the top of the cloud, negative charge pools in the middle, and sometimes a smaller positive region forms near the base. This separation creates enormous electric fields, stretching across kilometers of turbulent air.

The Invisible Electric Tension in the Sky

Electric fields inside thunderstorms can grow astonishingly strong. They are created by the separation of charge and represent stored electrical energy, waiting for a way to be released. However, air is normally an excellent electrical insulator. Even with enormous voltage differences, the air resists breakdown.

This is one of the central puzzles of lightning physics. Measurements suggest that the electric fields inside clouds are often not strong enough, on their own, to overcome air’s insulating properties. Yet lightning occurs anyway. This implies that additional processes amplify or localize electric fields, creating narrow regions where breakdown becomes possible.

Turbulence plays a key role. The cloud interior is a constantly shifting maze of updrafts, downdrafts, ice particles, and liquid droplets. Electric fields fluctuate rapidly in space and time, forming intense pockets that instruments struggle to detect. Lightning does not wait for the entire cloud to reach a critical threshold. It exploits local weaknesses, fleeting alignments where conditions suddenly become favorable.

The Birth of a Lightning Channel

When lightning finally begins, it does not appear as a single, smooth bolt. Instead, it starts with a subtle and complex process called a stepped leader. This leader is a faint, branching channel of ionized air that moves downward from the negatively charged region of the cloud toward the ground.

The stepped leader advances in jumps, not continuously. Each step lasts only microseconds and extends the channel by tens of meters. Between steps, the leader pauses, as if probing the air ahead. During this time, it branches repeatedly, exploring multiple paths at once.

This branching behavior is a major reason lightning is so unpredictable. The leader is not following a single predetermined route. It is responding to microscopic variations in air density, humidity, electric field strength, and the presence of objects on the ground. Each branch competes, and only one ultimately connects with the surface.

The Ground’s Hidden Role in Lightning Strikes

Lightning is not a one-sided attack from cloud to Earth. The ground actively participates. As the stepped leader approaches, the electric field at the surface intensifies dramatically. Tall objects, trees, buildings, and even small protrusions like blades of grass can respond by launching upward-moving discharges called upward streamers.

These streamers are invisible to the naked eye but crucial to the final strike. The lightning channel is completed when a downward-moving leader connects with an upward streamer. At that instant, the circuit closes, and a powerful return stroke races upward along the ionized path, producing the blinding flash and thunder we observe.

Which object launches the successful streamer is determined by a complex interplay of geometry, conductivity, electric field enhancement, and pure chance. A taller object may seem more likely to be struck, but this is not guaranteed. Subtle differences in shape, surface moisture, and surrounding structures can tip the balance.

This means lightning does not simply “choose” the tallest or most conductive target. It connects where conditions align at precisely the right moment.

Why Exact Prediction Is So Difficult

Predicting exactly where lightning will strike would require knowing, in real time, the precise electric field structure inside a storm and near the ground at extremely fine scales. This is far beyond our current capabilities.

Thunderstorms are chaotic systems. Small differences in initial conditions can grow rapidly, leading to vastly different outcomes. This sensitivity is a hallmark of chaos, where long-term or precise predictions become practically impossible even if the governing laws are known.

Electric fields fluctuate on scales of meters and microseconds, while most measurement tools operate on much coarser scales. Instruments placed inside storms face extreme conditions and provide only limited snapshots. Remote sensing techniques, such as radar and satellites, reveal storm structure but cannot resolve the microscopic electrical details that determine a strike point.

Even if we could measure everything perfectly, the branching nature of lightning introduces an element of inherent unpredictability. The leader explores many possible paths simultaneously. The final connection depends on random fluctuations at the smallest scales, where thermal motion, ionization events, and turbulence dominate.

The Myth of Simple Lightning Rules

Popular advice about lightning safety often relies on simplified rules: lightning strikes the tallest object, lightning avoids certain materials, lightning follows metal. While these ideas contain partial truths, they can be misleading.

Height increases the likelihood of launching an upward streamer, but it does not guarantee a strike. Metal does not attract lightning, though it conducts electricity efficiently once a strike occurs. Lightning does not consciously seek targets; it responds to electric fields and available pathways.

These misconceptions persist because lightning feels intentional. Its dramatic, singular strikes give the illusion of choice. In reality, lightning is the outcome of countless microscopic processes aligning in a brief moment.

Understanding this helps explain why exact prediction is so elusive. There is no simple rule to apply, no single variable to measure.

The Limits of Modern Lightning Detection

Modern technology has dramatically improved our ability to detect lightning. Networks of ground-based sensors can locate strikes by measuring radio waves emitted during discharges. Satellites can observe lightning flashes from space, mapping global patterns of activity.

These systems are invaluable for weather forecasting, aviation safety, and climate research. They can tell us when and where lightning has occurred and identify regions at higher risk. What they cannot do is predict the precise strike location before it happens.

Detection works after the fact or at best during the event. Prediction would require foresight into the branching leader’s future path, something that remains beyond reach.

Lightning as a Multiscale Problem

One of the deepest challenges in lightning physics is that it operates across an enormous range of scales. At the largest scale, thunderstorms span tens of kilometers and are driven by atmospheric circulation and solar heating. At intermediate scales, cloud microphysics governs particle collisions and charge separation. At the smallest scales, ionization and electron motion determine how a leader propagates.

These scales are tightly coupled. Changes at the microscopic level can influence macroscopic behavior, and vice versa. Modeling such a system requires enormous computational power and detailed knowledge of processes that are still not fully understood.

This multiscale nature places lightning among the most difficult natural phenomena to predict, comparable to earthquakes and turbulence.

The Role of Cosmic Rays and Background Radiation

An intriguing aspect of lightning physics involves cosmic rays—high-energy particles that constantly bombard Earth from space. Some theories suggest that cosmic rays may help initiate lightning by producing free electrons that seed ionization in strong electric fields.

While this idea does not solve the prediction problem, it highlights the subtle influences at play. Lightning may be triggered by factors entirely external to the storm, adding another layer of randomness.

If true, this means lightning initiation could depend partly on stochastic events beyond Earth’s atmosphere, further complicating prediction efforts.

Why Even Nearby Objects Are Not Safe or Certain Targets

One of the most unsettling aspects of lightning is its apparent randomness at close range. Two identical trees standing side by side may experience very different fates. One is struck repeatedly, the other never.

This is not because one tree is favored, but because the precise conditions required for a streamer connection rarely repeat in the same way. Slight differences in moisture content, internal structure, surrounding airflow, or even the electric field history of previous strikes can influence outcomes.

Lightning remembers, in a sense. A previous strike can alter the conductivity of a channel, making repeat strikes more likely along similar paths. Yet this memory is imperfect and fades as conditions change.

Human Efforts to Control or Influence Lightning

Throughout history, humans have tried to tame lightning. The invention of the lightning rod was a major success, providing a preferred conductive path to ground and reducing damage to structures. However, even lightning rods do not prevent strikes; they merely manage them.

Modern research explores triggering lightning using rockets trailing conductive wires or powerful lasers that ionize air. These experiments demonstrate that lightning paths can be influenced under controlled conditions, but scaling such methods to natural storms and wide areas is impractical.

These efforts underline an important truth: influencing lightning locally is possible, but predicting or controlling it globally remains out of reach.

Emotional Weight of Uncertainty

The inability to predict lightning precisely carries emotional weight. Lightning kills people, damages infrastructure, and disrupts lives. Each unpredictable strike is a reminder of vulnerability.

At the same time, this uncertainty adds to lightning’s power as a symbol. It represents nature’s refusal to be fully domesticated, a flash of wildness in an increasingly engineered world.

Physics does not promise complete control. It offers understanding, probabilities, and risk reduction. Lightning teaches humility, showing that even with deep knowledge, uncertainty remains.

What Physics Has Taught Us So Far

Despite the challenges, physics has revealed much about lightning. We understand charge separation mechanisms, leader propagation, streamer formation, and energy release with remarkable detail. High-speed cameras and sensitive detectors have uncovered structures invisible to the naked eye, such as fast radio bursts and gamma-ray flashes associated with lightning.

Each discovery deepens our appreciation of lightning’s complexity. Rather than simplifying the phenomenon, knowledge has revealed layers of subtlety that explain why prediction is so hard.

The Future of Lightning Research

Future advances may improve probabilistic forecasting. Better sensors, machine learning, and more detailed models could identify regions and moments of heightened risk with greater precision. We may learn to predict lightning likelihood on smaller scales than ever before.

However, exact point prediction—knowing the precise tree or building that will be struck seconds in advance—may remain fundamentally impossible. The combination of chaos, multiscale interactions, and stochastic triggers sets a hard limit.

Accepting this does not mean giving up. It means redefining success in realistic terms, focusing on safety, resilience, and respect for natural forces.

Lightning as a Lesson in the Nature of Science

Lightning physics offers a profound lesson about science itself. Science is not the elimination of mystery but its careful illumination. Each answer reveals deeper questions. Each measurement exposes new uncertainties.

Lightning reminds us that understanding does not always grant control. Sometimes, it grants perspective. It shows how order emerges from chaos, how simple laws produce complex behavior, and how nature operates at the edge of predictability.

The Flash That Still Defies Us

When lightning splits the sky, it is over in an instant. Yet that instant carries the weight of centuries of inquiry and unanswered questions. We know how lightning forms, how it moves, how it releases energy. We know how to reduce its dangers and study its patterns.

What we do not know—and may never fully know—is exactly where the next bolt will strike.

That uncertainty is not a failure of physics. It is a reflection of reality itself. Lightning exists at the boundary where determinism meets chance, where order meets turbulence. It is a reminder that the universe is not a machine that always reveals its next move, but a dynamic, restless system that still holds surprises.

In every flash of lightning, physics speaks—not in complete sentences, but in fragments of brilliance, challenging us to listen, to learn, and to accept that some mysteries resist precise prediction, even as they invite endless wonder.