From the first moments when humans looked up at the stars and wondered what they were, two powerful forces began shaping our understanding of reality. One was curiosity—the hunger to observe, to measure, to explain. The other was belief—the need to find meaning, to make sense of the inexplicable, to feel connected to something larger than ourselves.

These two forces—science and belief—have danced with each other through the centuries, sometimes in harmony, sometimes in brutal conflict. Today, their relationship remains both fraught and fascinating. At the heart of it is a fundamental question: Can the tools of science and the truths of belief coexist, or are they destined to forever collide?

To understand that, we must go back—not just to Galileo or Darwin, but to the very roots of human consciousness.

The Brain Built for Both Wonder and Pattern

The human brain is a remarkable engine for survival. It’s not just a processor of information—it’s a storyteller. Long before formal science existed, our ancestors needed to explain lightning, illness, birth, death, and the changing seasons. Lacking microscopes or meteorology, they turned to the stories that made sense of chaos.

These stories became beliefs. Spirits caused storms. Gods made rivers flood. Ancestors watched over crops. And from these seeds, religion and mythology grew. In every culture, belief systems flourished—not because they were foolish, but because they worked. They gave people purpose, rules, hope, and a framework for understanding a terrifying and unpredictable world.

But even then, science—though not yet named—was quietly being born. The moment someone asked, “Why does the sun always rise in that direction?” or “What happens if I plant a seed at a different time?” a new mode of thinking began to emerge.

Science, at its core, is organized curiosity. It is not a body of facts but a method: observe, hypothesize, test, repeat. Over time, this method allowed humanity to peer deeper into the nature of reality—first with the naked eye, then with the telescope, the microscope, the particle accelerator, and now even with artificial intelligence.

So where, then, does belief fit into this growing cathedral of knowledge?

When the Earth Stood Still

Perhaps the most famous collision between science and belief came in the 17th century, when Galileo Galilei peered through his telescope and saw a universe that refused to behave the way religious authorities said it should.

The prevailing belief, based on centuries of theological interpretation, held that Earth was the unmoving center of the universe. The sun and planets orbited us because, of course, humans were the center of God’s creation.

But Galileo saw something else. He observed moons orbiting Jupiter, spots on the sun, and phases of Venus—evidence that the heavens were not perfect and unchanging. These observations supported the heliocentric theory of Copernicus: that the Earth moved around the sun, not the other way around.

The Church was not pleased. Galileo was tried by the Inquisition, forced to recant, and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. The conflict wasn’t purely about astronomy—it was about authority. If science could contradict scripture, then where did that leave the Church’s claim to truth?

Yet, history would vindicate Galileo. The Earth does orbit the sun. Science had spoken. But the trial left a scar that persists: the idea that science and belief are not just different, but enemies.

The Evolution of a Clash

Two centuries later, the battle reignited—this time not in the stars, but in the soil.

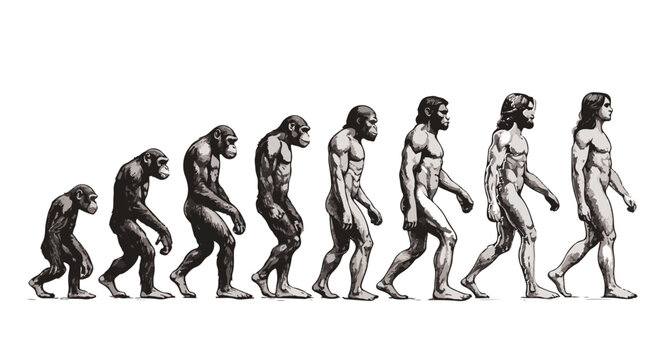

In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Using evidence from fossils, anatomy, and natural history, he proposed that life evolved through natural selection—a slow, unguided process that needed no divine hand.

The implications were seismic. If all life had evolved from a common ancestor, then humans were not specially created beings but part of a vast, interconnected web of biology. The elegant simplicity of Darwin’s idea came at the cost of a cherished belief: that humanity held a unique place in the universe.

For many religious thinkers, this was a bridge too far. Evolution seemed to reduce us to animals, to deny the soul, to undermine morality. The debate flared, especially in the United States, where public schools, churches, and courtrooms became battlegrounds for the soul of science education.

Even today, over 160 years later, the fight continues. Despite overwhelming evidence from genetics, geology, and paleontology, a significant portion of the population still rejects evolution, citing religious belief.

But does it have to be one or the other?

Two Ways of Knowing

The mistake often made—by both sides—is assuming that science and belief must answer the same questions.

Science seeks to explain how the world works. It is empirical, testable, falsifiable. It measures particles, maps galaxies, and decodes DNA. It does not concern itself with meaning, purpose, or morality—except as questions of human behavior.

Belief, particularly in the form of religion, often seeks to answer why the world exists. It addresses questions of purpose, ethics, and spiritual experience. These are not easily measured by experiments, but they are no less real to the people who feel them.

Problems arise when belief makes claims about the physical world that contradict scientific evidence. Saying that the Earth is 6,000 years old is not a question of faith—it is a claim about geology, astronomy, and biology, and it can be tested (and has been, extensively).

Likewise, science oversteps when it claims to disprove belief systems that deal in meaning rather than mechanism. Saying “God does not exist” is not a scientific conclusion—it is a philosophical stance. Science can say that the universe can function without divine intervention, but it cannot prove or disprove purpose.

In this light, science and belief are not necessarily enemies. They are different lenses through which we view the same world—one sharp and empirical, the other symbolic and moral.

When Scientists Believe

It’s tempting to think that scientists are by definition atheists, and that religion belongs to those ignorant of science. But the reality is more nuanced.

Many great scientists have been people of faith. Isaac Newton believed deeply in a Creator, seeing his laws of motion as divine order made visible. Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics, was a monk. Georges Lemaître, the physicist who proposed the Big Bang theory, was a Catholic priest. Even today, a sizable portion of scientists around the world identify as religious or spiritual.

Albert Einstein, though not traditionally religious, often spoke in spiritual terms. He rejected a personal God, but marveled at what he called the “cosmic religious feeling”—the awe and humility that comes from contemplating the laws of the universe.

“I want to know God’s thoughts,” he once said. “The rest are details.”

This blending of scientific awe with spiritual reverence suggests that the line between science and belief is not always bright. For many, the more we understand the universe, the deeper our sense of wonder—and the more profound our sense of mystery.

The Rise of Fundamentalism and Scientific Denial

Despite the potential for harmony, the modern world has seen a troubling resurgence of conflict. In some religious circles, science is viewed with deep suspicion. Climate change, vaccines, evolution—entire fields are dismissed not on evidence, but on perceived ideological grounds.

This backlash is often fueled by fear: fear that science undermines traditional values, that it leads to moral relativism, or that it promotes a cold, meaningless view of existence.

But anti-scientific sentiment is not limited to the religious. In secular circles, belief takes new forms—conspiracy theories, pseudoscience, anti-vaccine movements, and even technological utopianism. These are not grounded in scientific evidence, but in emotional narratives that mimic religious belief in structure and intensity.

Humans are belief-forming creatures. We seek patterns, heroes, villains, and cosmic purpose. In the absence of traditional religion, we often invent new ones. Science is powerful, but it does not eliminate our psychological need for belief. If anything, it must reckon with it.

Bridging the Divide

So how do we reconcile these two powerful ways of knowing? Is peaceful coexistence possible?

Some thinkers propose a model called “non-overlapping magisteria,” introduced by the late evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould. He argued that science and religion occupy separate domains of authority: science deals with empirical facts; religion deals with moral values. If each respects the boundaries of the other, conflict can be avoided.

But the reality is messier. Belief often bleeds into science education, and scientific discoveries often reshape moral worldviews.

Rather than erect walls, a better approach may be to cultivate humility on both sides.

Science, for all its triumphs, does not yet know what consciousness is, or how life began, or what happened before the Big Bang. It is an ever-growing body of knowledge, but it is also a method that acknowledges uncertainty and thrives on revision.

Belief, at its best, is not dogma but a living tradition—a means of making sense of our experiences, guiding our ethics, and connecting us to one another. When it becomes rigid and resistant to evidence, it strays from its strength.

Dialogue, education, and empathy are the keys. Teaching science with clarity and enthusiasm is vital, but so is recognizing the emotional and existential needs that belief fulfills.

The Future: A Unified Vision?

As we stand on the threshold of breathtaking advances—AI, genetic engineering, quantum computing—the stakes of the science-vs-belief conversation have never been higher.

Will artificial intelligence challenge our ideas of the soul and consciousness? Will neuroscience explain away free will? Will we use genetic tools to “improve” humanity, and if so, by whose standards?

These are not just scientific questions. They are deeply moral and philosophical. And they will require the insights of both scientists and ethicists, both empirical thinkers and spiritual leaders.

The future may not lie in choosing between science and belief, but in forging a new synthesis—one that honors reason without sacrificing meaning, and that embraces knowledge without losing awe.

Because ultimately, science and belief share the same origin: a yearning to understand who we are, where we came from, and what, if anything, lies beyond the stars.