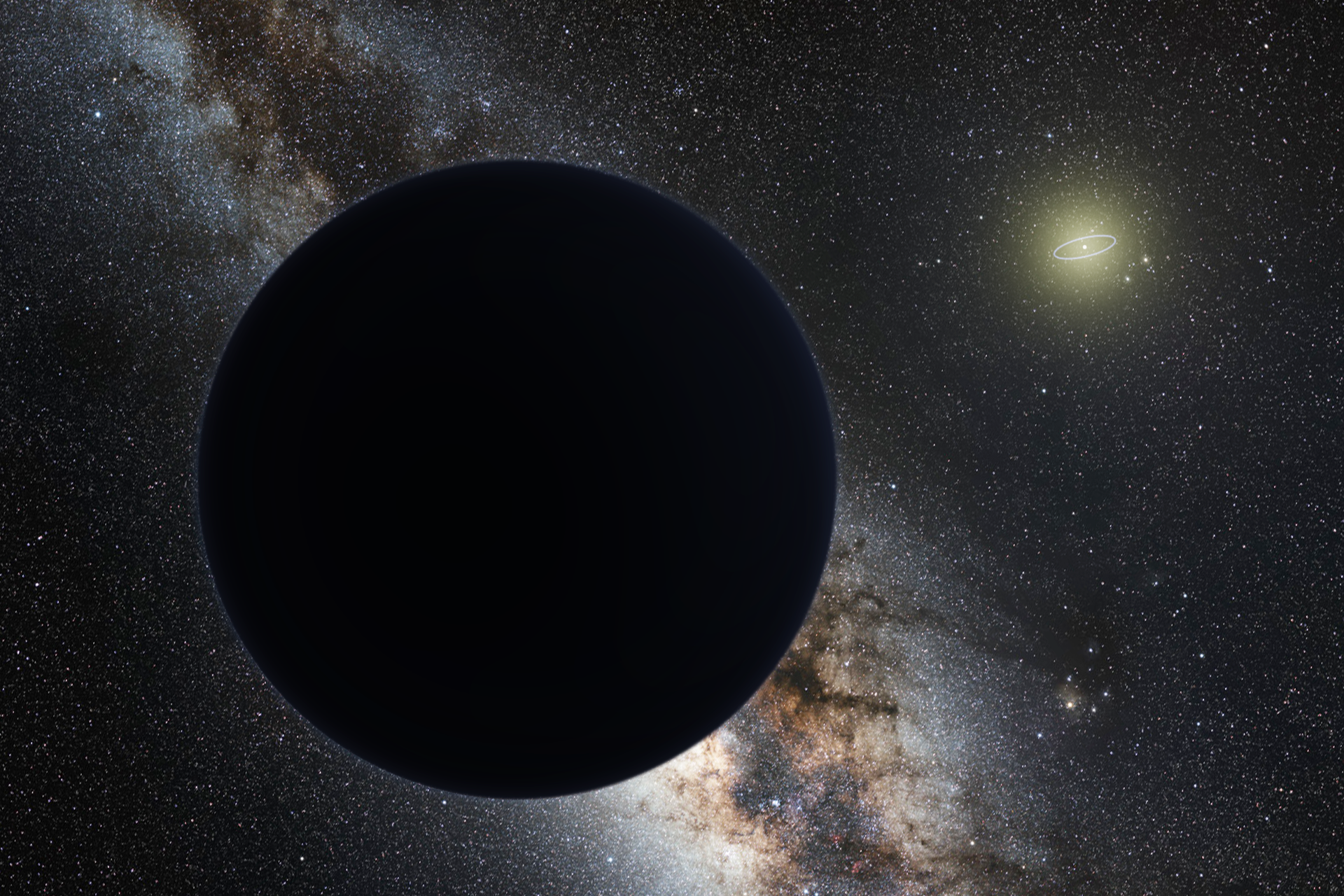

The Solar System has long seemed like a completed map. Eight planets circle the Sun in orderly paths, their motions predicted with extraordinary precision, their properties measured by spacecraft and telescopes, their histories woven into textbooks and popular imagination alike. For many decades after the discovery of Neptune in 1846 and Pluto in 1930, astronomers believed that the major planetary architecture of our cosmic neighborhood was essentially known. Yet science rarely ends with closure. In recent years, an unexpected and deeply intriguing possibility has emerged from the cold outskirts of the Solar System: a massive, unseen planet may still be lurking far beyond Neptune, silently shaping the orbits of distant objects. This hypothetical world is known as Planet Nine.

The search for Planet Nine is not merely a hunt for another celestial body. It is a story about patterns and anomalies, about the power of gravitational inference, and about how modern astronomy continues to revise even our most familiar cosmic surroundings. It is a narrative that blends rigorous mathematics with a sense of mystery, reminding us that discovery is often born from subtle irregularities rather than dramatic sightings.

A Solar System That Refused to Be Finished

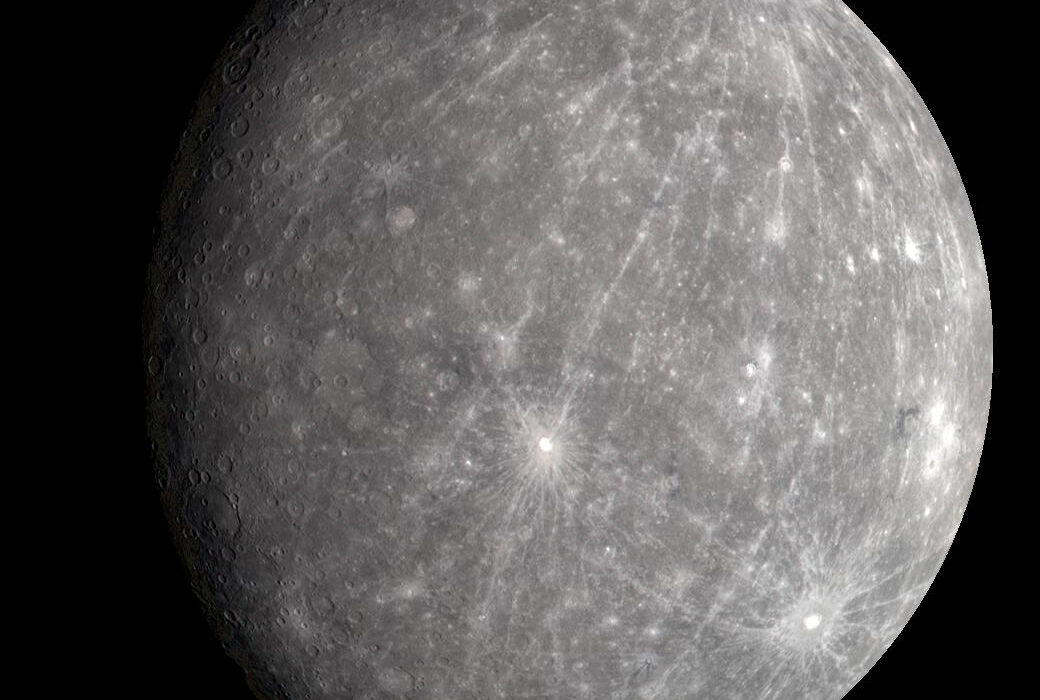

For much of the twentieth century, the Solar System was presented as a neat hierarchy. Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars formed the rocky inner planets, while Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune dominated the outer regions as gas and ice giants. Pluto, discovered by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930, occupied a peculiar position, initially hailed as the ninth planet before being reclassified decades later as a dwarf planet. This reclassification, formalized in 2006 by the International Astronomical Union, reflected a growing recognition that Pluto was part of a much larger population of icy bodies beyond Neptune.

This region, known as the Kuiper Belt, is a vast disk of debris left over from planetary formation. It contains countless small objects, including dwarf planets such as Eris, Haumea, and Makemake. Beyond the Kuiper Belt lies the even more distant scattered disk and, farther still, the hypothesized Oort Cloud. These remote domains are difficult to observe directly, yet they preserve crucial clues about the Solar System’s past.

As astronomers began to catalog these distant objects with greater precision, something unexpected emerged. Certain Kuiper Belt objects exhibited unusual orbital patterns that seemed statistically unlikely to occur by chance alone. Their elongated orbits appeared clustered in space, pointing in roughly the same direction, as if shepherded by an unseen gravitational influence. This subtle but persistent anomaly would eventually give rise to the Planet Nine hypothesis.

The Distant Edge of the Solar System

To understand why Planet Nine was proposed, one must first appreciate the environment in which its influence is suspected. The outer Solar System is a realm of extreme distances and long timescales. Neptune orbits the Sun at an average distance of about 30 astronomical units, where one astronomical unit is the average distance between Earth and the Sun. Beyond Neptune, sunlight grows faint, temperatures plunge, and orbital periods stretch into centuries or millennia.

The Kuiper Belt extends roughly from 30 to 50 astronomical units, containing objects whose orbits are relatively stable and moderately inclined. The scattered disk overlaps this region but includes objects with highly eccentric and tilted orbits, likely shaped by gravitational interactions with Neptune during the early Solar System. Some of these objects, known as extreme trans-Neptunian objects, travel hundreds of astronomical units from the Sun at their farthest points.

It was among these extreme objects that astronomers noticed something peculiar. Instead of being randomly oriented, several of their orbits appeared to share a common alignment. Their closest approaches to the Sun occurred in similar directions, and their orbital planes were similarly tilted. Given the chaotic gravitational environment of the outer Solar System, such coherence was difficult to explain without invoking an additional massive body.

Patterns Written in Gravity

Gravity is the invisible architect of planetary motion. Even when a massive object cannot be seen directly, its presence can be inferred from the way it tugs on other bodies. This method has a rich history in astronomy. Neptune itself was discovered through mathematical prediction rather than direct observation, after irregularities in Uranus’s orbit suggested the influence of an unseen planet.

The case for Planet Nine follows a similar logic, though the evidence is subtler. In 2016, astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Michael Brown presented a detailed analysis of several extreme Kuiper Belt objects whose orbits seemed improbably clustered. Through extensive simulations, they showed that a distant, massive planet could naturally produce the observed orbital alignment over billions of years.

According to their models, Planet Nine would likely be several times more massive than Earth, perhaps comparable in mass to a small ice giant. Its orbit would be highly elongated, carrying it hundreds of astronomical units from the Sun, with an orbital period measured in tens of thousands of years. Such a planet would be far too faint to have been detected by earlier surveys, especially if it currently lies near the farthest point of its orbit.

What Planet Nine Might Be Like

If Planet Nine exists, it would represent a new class of object within our Solar System. It would not resemble the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, nor would it fit neatly alongside Uranus and Neptune. Instead, it is often envisioned as a super-Earth or mini-Neptune, composed of rock, ice, and possibly a thick atmosphere of hydrogen and helium.

Its extreme distance from the Sun would place it in perpetual twilight. Even at its closest approach, the Sun would appear as a brilliant star rather than a blazing disk. Temperatures on Planet Nine would be unimaginably cold, likely only a few tens of degrees above absolute zero. Yet beneath this frigid exterior, internal heat generated by radioactive decay and residual formation energy could still play a role in shaping its structure.

The planet’s orbit would be highly inclined relative to the plane in which most planets orbit, an unusual feature that raises questions about its origin. Such an orbit suggests a turbulent past, possibly involving gravitational interactions with other massive bodies during the Solar System’s formative years.

Origins: Born Here or Captured from Afar?

One of the most compelling aspects of the Planet Nine hypothesis concerns how such a planet might have come to occupy its distant, eccentric orbit. Two broad possibilities are often discussed: Planet Nine formed within the Solar System and was later scattered outward, or it formed elsewhere and was captured by the Sun’s gravity.

In the early Solar System, planets are thought to have formed within a dense disk of gas and dust. Gravitational interactions between growing planets could have led to dramatic rearrangements, including the outward scattering of some bodies. In this scenario, Planet Nine may have formed closer to the Sun before being flung into the outer reaches during a chaotic period of planetary migration.

Alternatively, Planet Nine could be a rogue planet, formed around another star and later captured by the Sun as it passed through a crowded stellar nursery. Young stars often form in clusters, where close encounters are more common. Under the right conditions, a passing star could lose a planet to the Sun’s gravitational pull, leaving it bound in a distant orbit.

Both scenarios are plausible within current models of planetary formation, and distinguishing between them would offer valuable insight into the history of our Solar System and the processes that shape planetary systems more generally.

Alternative Explanations and Scientific Debate

Despite its elegance, the Planet Nine hypothesis is not universally accepted. Science advances through skepticism as much as through imagination, and many astronomers have explored alternative explanations for the observed orbital clustering.

One possibility is that observational bias plays a significant role. Detecting distant objects is inherently difficult, and surveys tend to focus on specific regions of the sky. This uneven coverage could create the illusion of clustering where none exists. Some studies have argued that when these biases are carefully accounted for, the statistical significance of the alignment diminishes.

Another alternative involves the collective gravitational influence of many smaller objects rather than a single large planet. In this view, the combined mass of the Kuiper Belt and scattered disk could subtly shape orbits over long timescales. However, most models suggest that the total mass of these regions is too small to produce the observed effects.

There are also more speculative ideas involving modifications to gravity or the presence of a primordial black hole, though such proposals remain far outside mainstream consensus. The debate surrounding Planet Nine illustrates the healthy tension between hypothesis and evidence that characterizes scientific progress.

The Challenge of Seeing the Unseen

If Planet Nine exists, why has it not been directly observed? The answer lies in the immense scale of the Solar System and the limitations of current observational technology. At distances hundreds of times greater than Earth’s from the Sun, even a planet several times Earth’s mass would reflect very little sunlight. Against the backdrop of countless faint stars and galaxies, such an object would be extraordinarily difficult to detect.

Moreover, Planet Nine’s slow motion across the sky complicates its identification. Unlike nearer planets, which shift noticeably against the stars over days or weeks, a distant planet would move imperceptibly over short timescales. Detecting it requires repeated observations over months or years, combined with sophisticated data analysis.

Modern surveys using powerful telescopes and sensitive detectors have begun to probe these distant regions more systematically. Instruments such as wide-field optical surveys and infrared observatories are particularly well suited to the task, as Planet Nine may emit faint thermal radiation from its internal heat.

The Role of Simulations and Predictive Models

In the absence of direct detection, theoretical modeling plays a central role in the search for Planet Nine. Astronomers use numerical simulations to explore how different planetary configurations would influence the orbits of known objects. By comparing these simulated outcomes with actual observations, they can narrow down the possible properties and locations of the hypothetical planet.

These simulations suggest that Planet Nine’s influence extends beyond orbital clustering. It could also explain the presence of objects with extreme orbital tilts, including some that orbit nearly perpendicular to the plane of the Solar System. Such behavior is difficult to produce through interactions with known planets alone.

As more distant objects are discovered and their orbits precisely measured, these models can be refined. Each new data point either strengthens or weakens the case for Planet Nine, gradually sharpening our understanding of the outer Solar System.

Observational Campaigns and the Modern Search

The search for Planet Nine has inspired a new generation of observational campaigns. Astronomers are systematically scanning large swaths of the sky, focusing on regions predicted by theoretical models. This effort requires patience, collaboration, and technological innovation.

Ground-based telescopes equipped with large digital cameras can capture wide fields of view, enabling astronomers to detect faint, slow-moving objects. Space-based observatories add another layer of capability, free from atmospheric distortion and sensitive to infrared wavelengths.

The process of searching is painstaking. Candidate objects must be distinguished from stars, galaxies, and transient phenomena. Their motion must be tracked over time to confirm whether they are bound to the Solar System. Even then, determining their mass and orbit requires careful analysis.

What Discovery Would Mean

The discovery of Planet Nine would be one of the most significant astronomical events of the modern era. It would reshape our understanding of the Solar System’s architecture and formation history. It would demonstrate that even in our cosmic backyard, major discoveries remain possible.

Beyond the Solar System, Planet Nine would have broader implications for planetary science. It would provide a nearby example of a super-Earth or mini-Neptune, a class of planets known to be common around other stars but absent from the traditionally defined Solar System. Studying such a planet up close, even from afar, would offer valuable comparative insights.

Perhaps most importantly, the discovery would underscore the power of indirect evidence in science. It would affirm that careful attention to anomalies, combined with rigorous modeling, can reveal hidden aspects of reality long before they are directly observed.

If Planet Nine Does Not Exist

Equally profound would be the conclusion that Planet Nine does not exist. If further observations and analyses ultimately rule out the planet, scientists would be compelled to seek new explanations for the observed orbital patterns. This outcome would still represent progress, prompting refinements in our understanding of the Kuiper Belt, observational biases, and gravitational dynamics.

Science advances not only through confirmation, but through the elimination of possibilities. The process of testing the Planet Nine hypothesis has already led to improved surveys, more detailed models, and a deeper appreciation of the Solar System’s complexity. In this sense, the search itself is valuable, regardless of its final outcome.

A Reminder of Cosmic Humility

The story of Planet Nine is a reminder that our knowledge of the universe is always provisional. Even the Solar System, studied for centuries and visited by spacecraft, still holds secrets. The vast distances and faint signals involved challenge our instruments and our patience, yet they also inspire a sense of wonder.

In contemplating the possibility of a hidden planet, we are reminded that discovery often begins not with certainty, but with curiosity. It begins with noticing that something does not quite fit, with asking whether there might be more than meets the eye. The search for Planet Nine embodies this spirit, blending careful analysis with imaginative reach.

The Ongoing Journey

As of now, Planet Nine remains hypothetical, a ghostly presence inferred from the motions of distant worlds. Its existence is neither confirmed nor disproven, suspended between mathematical prediction and observational pursuit. Yet this uncertainty is not a weakness; it is the essence of scientific exploration.

The search continues, driven by new data, improved technology, and the enduring human desire to understand our place in the cosmos. Whether Planet Nine is eventually found or not, the effort to find it enriches our understanding of the Solar System and demonstrates that even familiar territories can yield profound surprises.

In the quiet darkness beyond Neptune, something may indeed be hiding. Or perhaps the true discovery lies not in a single distant planet, but in the deeper insights gained by seeking it.