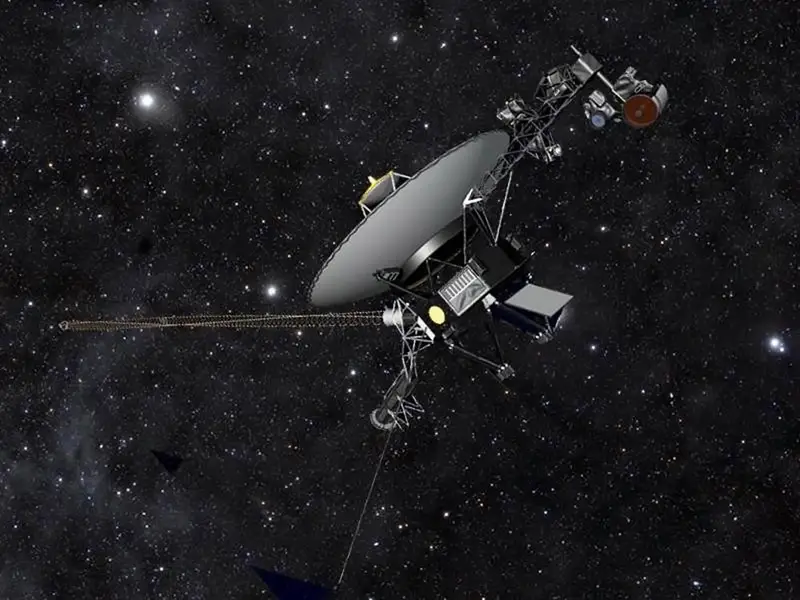

In the vast darkness beyond the known planets, far beyond the warmth of the Sun and the familiar rhythms of Earth’s sky, a small human-made object continues its silent journey. Voyager 1, launched in 1977, is now farther from Earth than any other spacecraft ever built. It is a machine born in the analog age, designed with slide rules and early computers, yet it still endures in an environment no human-made object was ever expected to survive for so long. Its story is not only about distance and technology, but about curiosity, patience, and the human desire to reach beyond the visible horizon.

The question “Where is Voyager 1 now, and is it still talking to us?” captures something deeper than simple location or operational status. It reflects a longing to know whether a voice from humanity’s distant past is still whispering across interstellar space, whether a fragile connection remains between Earth and a probe that has crossed into a realm no spacecraft had entered before. To answer this question fully, one must understand not only where Voyager 1 is physically, but what it has become scientifically and symbolically over nearly half a century of travel.

The Mission That Was Never Meant to Last Forever

Voyager 1 was conceived during a unique moment in scientific history. In the 1960s, astronomers realized that a rare alignment of the outer planets would occur in the late 1970s, allowing a spacecraft to visit multiple giant planets using gravity assists. This alignment, which happens roughly once every 176 years, offered an unprecedented opportunity to explore Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune in a single mission. The result was the Voyager program, consisting of two nearly identical spacecraft: Voyager 1 and Voyager 2.

Although Voyager 2 ultimately visited more planets, Voyager 1 followed a trajectory optimized for a close encounter with Saturn and its large moon Titan. This choice meant that Voyager 1 would be flung out of the plane of the planets after its Saturn flyby, ending any possibility of visiting Uranus or Neptune. At the time, this was considered an acceptable trade-off. No one expected either spacecraft to remain operational for decades, let alone venture into interstellar space.

Voyager 1 was designed with a primary mission lasting only a few years. Engineers built it to survive the harsh radiation environment of Jupiter and the cold distances of Saturn, but the idea that it would still be functioning nearly fifty years later was beyond reasonable expectation. Its longevity is not the result of overengineering alone, but of careful management, ingenuity, and an extraordinary understanding of the spacecraft’s systems by generations of engineers who were not even born when it was launched.

Leaving Earth and Redefining Distance

Voyager 1 was launched on September 5, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida. At the time, Earth’s population was grappling with the Cold War, rapid technological change, and a growing awareness of humanity’s place in the cosmos. The spacecraft carried instruments to study magnetic fields, plasma, cosmic rays, and planetary atmospheres. It also carried something far more symbolic: the Golden Record, a phonograph disc containing sounds, music, images, and greetings from Earth, intended as a message to any intelligent beings who might encounter it in the distant future.

As Voyager 1 traveled outward, it quickly began to redefine what “far away” meant. It passed the orbit of Mars in months, Jupiter in 1979, and Saturn in 1980. Each encounter transformed scientific understanding. At Jupiter, Voyager 1 discovered active volcanism on Io, a revelation that reshaped planetary science. At Saturn, it revealed complex ring structures and provided detailed observations of Titan, whose thick atmosphere hinted at chemical processes similar to those that may have existed on early Earth.

After Saturn, Voyager 1’s trajectory carried it upward and outward, away from the plane of the solar system. From that moment onward, it became not just a planetary explorer, but a pathfinder into the unknown. Distance ceased to be measured in terms of planetary orbits and began to be expressed in astronomical units and, eventually, light-hours of communication delay.

The Pale Blue Dot and a Turning Point

One of Voyager 1’s most iconic moments came in 1990, when it was commanded to turn its cameras back toward the inner solar system. From a distance of about 6 billion kilometers, Voyager 1 captured a series of images that included Earth as a tiny point of light suspended in a sunbeam. This image, later known as the “Pale Blue Dot,” profoundly influenced public perception of humanity’s place in the universe.

Shortly after taking these images, Voyager 1’s cameras were turned off to conserve power. Its mission priorities shifted fully toward studying the environment beyond the planets. This decision marked a turning point. Voyager 1 was no longer an explorer of worlds with names and familiar features, but an instrument drifting toward the boundary between the Sun’s influence and the vast interstellar medium beyond.

The spacecraft entered what is known as the heliosphere, a bubble formed by the solar wind, the continuous flow of charged particles streaming outward from the Sun. Understanding the shape and extent of this bubble became one of Voyager 1’s most important scientific goals, even though this was never part of the original mission plan.

Crossing the Edge of the Sun’s Domain

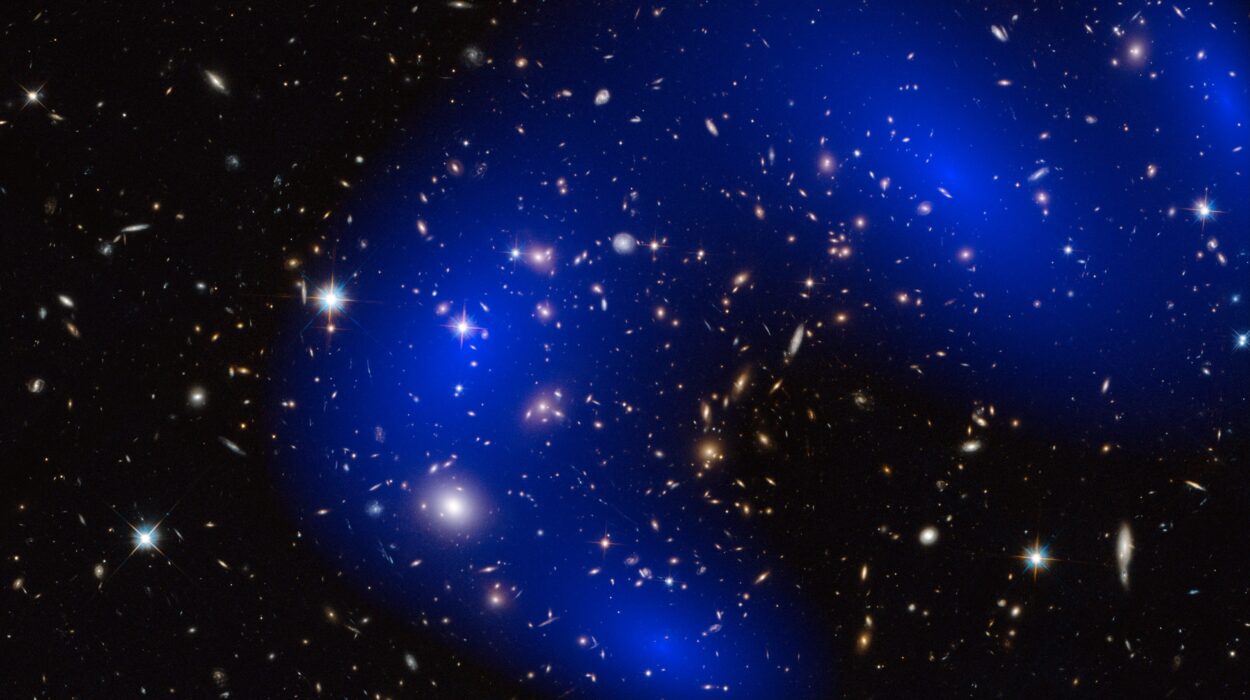

For decades, scientists debated where the solar system truly ends. The planets do not mark its boundary, nor does the farthest reach of the Sun’s light. Instead, the edge is defined by the point at which the solar wind is no longer dominant and gives way to the interstellar medium. This boundary includes several regions, including the termination shock, where the solar wind slows dramatically, and the heliopause, where the pressure of the solar wind balances that of interstellar space.

Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock in 2004, signaling that it had entered the heliosheath, a turbulent region filled with slowed and heated solar particles. For years afterward, scientists monitored changes in particle densities, magnetic fields, and cosmic rays, looking for signs that Voyager 1 was approaching the heliopause.

In 2012, Voyager 1 provided compelling evidence that it had crossed into interstellar space. Instruments detected a sharp drop in particles originating from the Sun and a corresponding increase in high-energy cosmic rays from outside the solar system. Although the magnetic field direction did not change as dramatically as some models predicted, the balance of evidence indicated that Voyager 1 had left the heliosphere and entered the local interstellar medium.

This moment marked a historic first. For the first time, a human-made object was directly sampling the environment between the stars. Voyager 1 had become an interstellar probe in the most literal sense.

Where Voyager 1 Is Now

As of the mid-2020s, Voyager 1 is more than 24 billion kilometers from Earth, a distance so immense that even light takes over 22 hours to travel one way between the spacecraft and our planet. It continues to move outward at a speed of roughly 17 kilometers per second relative to the Sun. This motion is not powered by engines; Voyager 1 has long since shut down its propulsion system. It coasts onward, guided by inertia and the gravitational influences it encountered decades ago.

Its location is often described in relation to the constellation Ophiuchus, although this is a line-of-sight reference rather than a meaningful navigational marker. In three-dimensional space, Voyager 1 is moving through a sparse region of interstellar gas and dust, far from any stars and unlikely to encounter another stellar system for tens of thousands of years.

From a human perspective, Voyager 1’s position is unimaginably remote. Yet from a cosmic perspective, it has barely begun its journey. The nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, is more than four light-years away. Voyager 1 would require tens of thousands of years to reach even that distance, and far longer to approach the denser regions of the Milky Way.

Is Voyager 1 Still Talking to Us?

Despite its age and distance, Voyager 1 has continued to communicate with Earth, though not without challenges. Communication occurs via NASA’s Deep Space Network, a global array of large radio antennas located in California, Spain, and Australia. These antennas are sensitive enough to detect Voyager 1’s faint signal, which arrives at Earth weaker than background noise and must be extracted through sophisticated signal processing.

Voyager 1 does not transmit continuously. Commands sent from Earth take nearly a full day to reach the spacecraft, and its responses take just as long to return. This time delay requires careful planning and patience. Engineers must anticipate potential issues well in advance and design commands that can safely execute without immediate human intervention.

In recent years, Voyager 1 has experienced several technical anomalies, reflecting the reality that it is operating far beyond its intended lifespan. Some of these issues have involved its onboard computer systems, including memory problems that temporarily affected the spacecraft’s ability to send usable scientific data. Through painstaking analysis and creative problem-solving, engineers were able to reconfigure systems, reroute functions, and restore meaningful communication.

As of the most recent updates, Voyager 1 continues to send engineering data and limited scientific measurements. While not all instruments remain operational, those that do still provide valuable information about magnetic fields, plasma waves, and cosmic rays in interstellar space. The spacecraft’s “voice” is faint and slow, but it has not yet fallen silent.

Power, Survival, and the Slow Fade Into Silence

Voyager 1 is powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which convert heat from the radioactive decay of plutonium into electricity. This power source was chosen because solar panels would be ineffective at the vast distances Voyager would reach. However, the output of these generators decreases gradually over time as the plutonium decays.

To manage this decline, mission controllers have systematically turned off instruments and heaters to conserve energy. Each decision represents a careful balance between preserving scientific capability and ensuring the spacecraft’s continued survival. Over the years, Voyager 1 has lost its cameras, some scientific instruments, and various subsystems, but its core communication and navigation functions have been maintained.

Eventually, the power will drop below the level required to operate even the most essential systems. When that happens, Voyager 1 will no longer be able to communicate with Earth. Estimates suggest that this may occur sometime in the early 2030s, although exact timelines depend on how efficiently power can be managed and how the remaining systems age.

When Voyager 1 finally falls silent, it will not stop existing. It will continue its journey indefinitely, carrying the Golden Record and the imprint of human curiosity into interstellar space. Its silence will not mark an end, but a transition from an active mission to a drifting artifact of civilization.

What Voyager 1 Is Teaching Us Now

Even in its extended mission, Voyager 1 continues to reshape scientific understanding. Direct measurements of the interstellar medium provide insights that cannot be obtained from Earth-based observations alone. Data on cosmic ray intensity, plasma density, and magnetic fields help scientists refine models of how stars interact with their galactic environment.

These measurements have implications beyond astrophysics. Understanding the interstellar medium informs theories about star formation, the propagation of cosmic radiation, and the broader structure of the Milky Way. Voyager 1’s data also serve as a reference point for future missions that may venture beyond the heliosphere with more advanced instruments.

Perhaps equally important is what Voyager 1 teaches about engineering and long-term exploration. Its continued operation demonstrates the value of robust design, thorough documentation, and institutional memory. Many of the engineers currently working on the mission were trained by predecessors who worked on the original spacecraft, creating a chain of knowledge spanning generations.

The Emotional Weight of a Distant Signal

There is something profoundly moving about the idea that a machine built in the 1970s is still communicating with Earth from interstellar space. Voyager 1’s signal carries not only data, but history. Each transmission represents a triumph over distance, time, and entropy.

For scientists and engineers, Voyager 1 is a reminder that exploration does not always yield immediate rewards. Some of its most important discoveries came decades after launch, long after public attention had shifted elsewhere. Its story underscores the importance of patience and sustained commitment in scientific inquiry.

For the broader public, Voyager 1 has become a symbol of humanity’s reach. It embodies the idea that even small, fragile creations can travel beyond all familiar boundaries, carrying messages of who we are and what we value. In a universe that often seems indifferent, Voyager 1 stands as evidence that curiosity itself can endure.

Voyager 1 and the Meaning of Distance

Distance in space is not merely a physical quantity; it is also a psychological and philosophical concept. Voyager 1 forces us to confront scales that defy everyday understanding. When we say it is billions of kilometers away, we are acknowledging a separation so vast that it reshapes our sense of proximity and connection.

Yet despite this distance, Voyager 1 remains linked to Earth through radio waves, mathematics, and intention. Its continued communication challenges the idea that remoteness implies isolation. In a very real sense, Voyager 1 is still part of human society, still responding to questions, still contributing to shared knowledge.

This paradox lies at the heart of space exploration. The farther we reach, the more we are reminded of both our smallness and our ingenuity. Voyager 1 is not just far away; it is a mirror reflecting humanity’s capacity to imagine, to build, and to persist.

The Future of Voyager 1’s Journey

Looking ahead, Voyager 1’s future is defined less by milestones than by gradual change. There will be no dramatic encounters, no sudden discoveries of alien worlds. Instead, there will be a slow accumulation of data, followed eventually by silence.

Long after its instruments shut down, Voyager 1 will continue drifting through the galaxy. Over tens of thousands of years, it will pass through different regions of interstellar space. Over millions of years, its trajectory will be subtly altered by gravitational influences. Over billions of years, it may outlast the Earth itself.

The Golden Record, attached to its side, may never be found. But its existence is not about likelihood. It is about intention. It represents a moment in human history when a species chose to speak to the cosmos, not with conquest or fear, but with music, images, and greetings.

Is Voyager 1 Still Talking to Us?

For now, the answer remains yes. Voyager 1 is still talking to us, though its voice is faint and its words are few. Each transmission is an achievement, a reminder that exploration is not always loud or dramatic. Sometimes it is quiet, persistent, and profoundly human.

One day, the signals will stop. The Deep Space Network will listen, and nothing will answer. That moment will not be a failure, but a culmination. Voyager 1 will have completed its role as a messenger, having carried our questions farther than ever before.

In the end, Voyager 1 is not just a spacecraft. It is a story written in radio waves and distance, a testament to what happens when curiosity is given time to travel. Where is Voyager 1 now? It is between the stars. Is it still talking to us? For a little while longer, yes, and in doing so, it reminds us that even across the immense silence of space, connection is possible.