Science is often imagined as a steady march toward truth, guided by evidence and reason alone. In reality, its path is far messier and more human. New ideas frequently collide with established beliefs, professional reputations, and deeply held intuitions about how the world ought to work. History shows that some of the most transformative scientific theories were not welcomed with applause, but with ridicule, skepticism, and even hostility. They were dismissed as absurd, unscientific, or the products of overactive imaginations—until evidence forced a reckoning.

These episodes are not stories of lone geniuses triumphing effortlessly over ignorance. They are reminders that science advances through tension, debate, and the slow accumulation of proof. They also reveal how difficult it can be for even trained scientists to abandon familiar frameworks when confronted with ideas that challenge common sense or entrenched authority.

The following five scientific theories were once mocked, doubted, or marginalized. Today, they form the foundations of modern scientific understanding. Their journeys from ridicule to acceptance illuminate how science really works—and why intellectual humility is one of its most essential virtues.

1. Continental Drift and the Theory of Plate Tectonics

In the early twentieth century, the idea that continents could move across Earth’s surface was widely regarded as laughable. The continents, after all, appeared solid and immovable, anchored firmly in place. To suggest that entire landmasses could drift over geological time seemed closer to fantasy than to serious science.

The theory of continental drift was proposed by Alfred Wegener, a German meteorologist, in 1912. Wegener observed that the coastlines of continents such as South America and Africa appeared to fit together like pieces of a puzzle. He also noted striking similarities in fossil species and rock formations found on continents now separated by vast oceans. To Wegener, the simplest explanation was that these continents were once joined together and had since drifted apart.

Despite the elegance of his observations, Wegener’s idea was met with widespread ridicule. Many geologists dismissed it outright, arguing that there was no plausible mechanism capable of moving continents through solid rock. The prevailing belief was that Earth’s crust was static, and that similarities between continents could be explained by land bridges that had since sunk beneath the ocean.

Wegener’s background outside geology further undermined his credibility. As a meteorologist, he was seen by many specialists as an outsider encroaching on their field. His inability to provide a convincing physical mechanism for continental movement proved to be a fatal weakness in the eyes of his critics.

For decades, continental drift remained on the fringes of scientific discourse. It was taught, if at all, as a historical curiosity rather than a serious theory. Wegener himself did not live to see his idea vindicated; he died in 1930 during an expedition in Greenland.

The turning point came in the mid-twentieth century, with advances in marine geology and geophysics. Detailed mapping of the ocean floor revealed vast mountain ranges running through the centers of oceans, now known as mid-ocean ridges. These ridges showed evidence of new crust forming and spreading outward, pushing older crust away. At the same time, studies of Earth’s magnetic field recorded in rocks revealed symmetrical patterns on either side of these ridges, consistent with seafloor spreading.

These discoveries provided the missing mechanism Wegener lacked. Continents were not plowing through solid rock; they were riding atop tectonic plates that moved slowly over Earth’s semi-molten mantle. Continental drift was absorbed into a broader framework known as plate tectonics, which now explains earthquakes, volcanoes, mountain formation, and the distribution of fossils with remarkable coherence.

What was once mocked as implausible speculation is now a unifying theory of Earth science. The continents do move, at rates of centimeters per year, reshaping the planet over millions of years. Wegener’s story stands as a powerful example of how correct ideas can be dismissed not because they are wrong, but because the evidence and tools needed to support them have not yet emerged.

2. Germ Theory of Disease

For much of human history, disease was explained through vague and often mystical concepts. Illness was attributed to imbalances in bodily fluids, known as humors, or to noxious airs called miasmas. The idea that invisible living organisms could invade the body and cause disease was, for centuries, considered implausible and even absurd.

The germ theory of disease, which holds that many illnesses are caused by microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses, did not emerge fully formed. It developed gradually through the work of several scientists, but its early proponents faced intense skepticism.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis observed that women giving birth in hospital wards staffed by doctors had significantly higher mortality rates from childbed fever than those attended by midwives. Semmelweis traced this difference to hygiene practices, noting that doctors often moved directly from performing autopsies to delivering babies without washing their hands. He introduced handwashing with chlorinated lime and saw mortality rates plummet.

Despite these dramatic results, Semmelweis was ridiculed by many of his peers. The suggestion that doctors themselves were responsible for transmitting disease was deeply offensive to professional pride. Without a clear understanding of microorganisms, his explanation seemed speculative and accusatory. Semmelweis was marginalized and died in relative obscurity.

Around the same time, Louis Pasteur was conducting experiments that challenged the notion of spontaneous generation, the belief that life could arise from non-living matter. Pasteur demonstrated that microorganisms came from existing microbes, not from inanimate substances. His work laid the foundation for understanding that specific organisms could cause specific diseases.

Even then, acceptance was slow. Many physicians resisted the idea that invisible germs were responsible for illness, preferring established theories that aligned with their training. It was not until the work of Robert Koch, who identified the bacteria responsible for diseases such as tuberculosis and anthrax, that germ theory gained widespread credibility. Koch’s postulates provided a systematic framework for linking specific microorganisms to specific diseases.

Once accepted, germ theory revolutionized medicine. It led to sterilization techniques, antibiotics, vaccines, and public health measures that dramatically increased life expectancy. What was once mocked as an affront to common sense—that unseen creatures could shape human health—became a cornerstone of modern biology and medicine.

The history of germ theory reveals how deeply cultural assumptions can delay scientific progress. It also shows how empirical evidence, patiently gathered and rigorously tested, can eventually overcome even the most entrenched resistance.

3. The Existence of Meteorites

Today, the idea that rocks fall from the sky seems unremarkable. Meteorites are collected, cataloged, and studied as valuable sources of information about the early solar system. Yet for centuries, the notion that stones could fall from space was treated as superstition or folklore.

Before the late eighteenth century, most natural philosophers believed that the heavens were perfect and unchanging. According to this worldview, celestial objects followed predictable paths, and Earth was isolated from the realm beyond its atmosphere. Reports of fiery objects streaking across the sky were often explained as atmospheric phenomena, such as lightning or combustion of gases.

When people claimed that solid stones had fallen from the sky, scientists typically dismissed these accounts as misunderstandings or fabrications. Some suggested that the stones had been struck by lightning, while others argued that they were ejected from volcanoes. The idea that rocks could originate in space was considered scientifically untenable.

The skepticism was so strong that museums refused to accept meteorite specimens, and scholars who supported their extraterrestrial origin risked damaging their reputations. Even when eyewitness accounts accumulated, they were often ignored or rationalized away.

The turning point came in 1794, when German physicist Ernst Chladni published a book arguing that meteorites were extraterrestrial in origin. Chladni assembled historical reports and physical evidence, proposing that these stones were fragments of cosmic bodies. His ideas were initially mocked, with critics deriding them as fanciful speculation.

Gradually, however, the evidence became overwhelming. In 1803, a dramatic meteorite shower occurred in L’Aigle, France, witnessed by thousands of people. Stones rained down over a wide area, leaving little room for alternative explanations. French scientist Jean-Baptiste Biot investigated the site and concluded that the stones had indeed fallen from space.

From that point on, the scientific consensus shifted. Meteorites were recognized as real, extraterrestrial objects, offering direct physical samples from beyond Earth. This realization expanded humanity’s understanding of its place in the cosmos and provided crucial insights into planetary formation.

The ridicule surrounding meteorites underscores how assumptions about the natural order can blind scientists to new possibilities. Sometimes, reality is not constrained by what seems reasonable within existing frameworks.

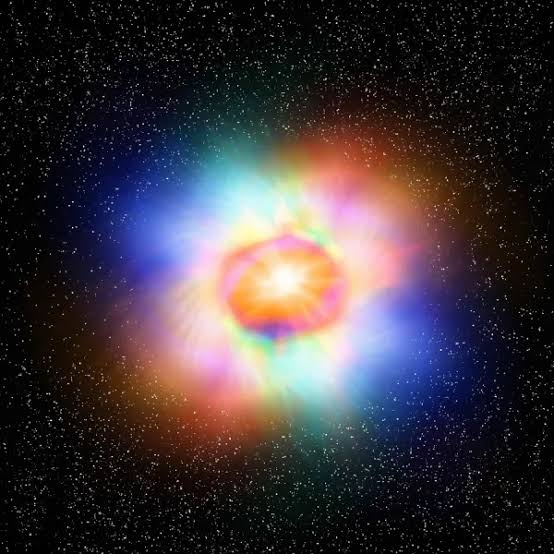

4. The Expanding Universe

For much of history, the universe was thought to be static and eternal. Stars and galaxies were assumed to occupy fixed positions, with no large-scale motion or evolution. This assumption was deeply ingrained, influencing both scientific models and philosophical beliefs.

In the early twentieth century, Albert Einstein applied his newly developed theory of general relativity to the universe as a whole. His equations suggested that the universe could not remain static; it must either expand or contract. Uncomfortable with this implication, Einstein introduced an additional term, known as the cosmological constant, to force his equations to yield a static universe.

Meanwhile, observational astronomy was undergoing a revolution. Edwin Hubble, using powerful telescopes, discovered that distant galaxies were moving away from Earth. More strikingly, the farther away a galaxy was, the faster it appeared to be receding. This relationship, now known as Hubble’s law, provided strong evidence that the universe itself was expanding.

At first, the idea of an expanding universe was met with skepticism and even ridicule. Many scientists found it philosophically troubling. A dynamic universe implied a beginning in time, raising questions that blurred the boundary between science and metaphysics. Some preferred alternative explanations, such as tired light theories, which suggested that light lost energy over distance rather than indicating cosmic expansion.

As evidence accumulated, resistance gradually weakened. Observations of cosmic background radiation and the distribution of galaxies reinforced the conclusion that the universe had evolved from a hotter, denser state. The expanding universe became a central pillar of cosmology.

Ironically, Einstein later reportedly referred to the cosmological constant as his “greatest blunder,” though modern discoveries of dark energy have given this term new relevance. The expansion of the universe, once mocked as an unnecessary complication, is now fundamental to our understanding of cosmic history.

This episode illustrates how deeply held assumptions can persist even in the face of mathematical and observational evidence. It also shows how scientific theories can evolve, incorporating elements once discarded or misunderstood.

5. The Existence of Atoms and the Reality of the Atomic World

The idea that matter is composed of tiny, indivisible units dates back to ancient philosophers such as Democritus. For centuries, however, atoms were regarded as philosophical abstractions rather than physical realities. By the nineteenth century, chemistry relied heavily on atomic concepts, yet many scientists remained skeptical that atoms truly existed.

Prominent physicists argued that atoms were merely convenient mathematical tools, not real objects. They pointed out that atoms could not be directly observed and questioned whether it was meaningful to assert their physical reality. This skepticism was especially strong among those committed to empirical observation as the foundation of science.

The debate intensified in the late nineteenth century, with influential scientists dismissing atomic theory as metaphysical speculation. Some argued that physics should concern itself only with measurable quantities, not hypothetical entities beyond direct detection.

The tide began to turn with the study of Brownian motion, the random movement of particles suspended in a fluid. In 1905, Albert Einstein provided a theoretical explanation for this phenomenon, showing that it could be explained by countless collisions with invisible molecules. His work allowed researchers to calculate the size and number of these molecules, linking theory with measurable effects.

Experimental confirmation soon followed. Jean Perrin conducted meticulous experiments that verified Einstein’s predictions, providing compelling evidence for the existence of atoms and molecules. These results convinced even many skeptics that atoms were not just useful fictions, but real constituents of matter.

Subsequent developments in atomic and quantum physics made the reality of atoms undeniable. Technologies such as electron microscopy and scanning tunneling microscopy eventually allowed scientists to image individual atoms directly, turning what was once mocked into something visible and tangible.

The acceptance of atoms transformed science, enabling advances in chemistry, materials science, electronics, and medicine. What began as a controversial hypothesis became one of the most secure foundations of modern knowledge.

Conclusion: Why Mockery Is Part of Scientific Progress

The stories of these five theories reveal a recurring pattern in the history of science. Ideas that challenge prevailing assumptions often encounter resistance, not because they lack merit, but because they disrupt established ways of thinking. Mockery, skepticism, and dismissal are not signs that science is failing; they are evidence that it is a human endeavor, shaped by culture, psychology, and institutional inertia.

At the same time, these stories highlight the self-correcting nature of science. Evidence matters. Experiments can be repeated, predictions tested, and theories refined or replaced. Over time, ideas that accurately describe reality tend to prevail, even if their acceptance is delayed.

Remembering theories that were once mocked and later proven true encourages intellectual humility. It reminds us that current consensus is not infallible, and that today’s fringe ideas may become tomorrow’s foundations. Science advances not by avoiding bold ideas, but by subjecting them to rigorous scrutiny, allowing reality itself to deliver the final verdict.

In this ongoing dialogue between imagination and evidence, ridicule may be loud, but truth, given time, has a way of making itself heard.