In the high-stakes world of modern artificial intelligence, systems can now draft legal briefs, debug software, and simulate complex human reasoning with startling fluidness. Yet, for all their digital sophistication, these models frequently stumble over a task taught to every eight-year-old: four-digit multiplication. It is a bizarre paradox of the digital age, a “jagged frontier” where a machine can explain quantum physics but fails to calculate $4,321 \times 1,234$. This mystery led a team of researchers from the University of Chicago, MIT, Harvard, Google DeepMind, and other institutions to peer into the “black box” of AI to understand why the simplest math remains so stubbornly difficult.

The Invisible Wall of the Local Optimum

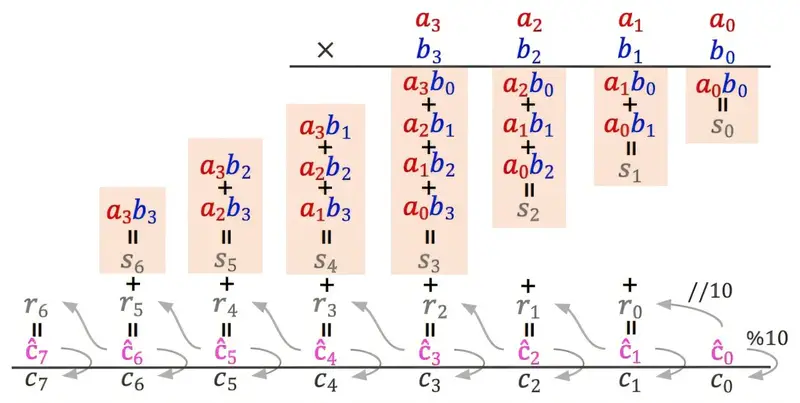

When a human multiplies large numbers, we don’t just see the answer in our mind’s eye. We follow a physical and mental ritual: we multiply digit pairs, we “carry” the one, and we carefully hold onto partial products until it is time to add them all together. In the world of computer science, these steps are known as long-range dependencies. They require a system to store a piece of information now and retrieve it much later in the process.

Most large language models learn by identifying patterns in massive datasets. To improve them, engineers typically use standard fine-tuning, which involves adding more data or increasing the number of layers—the internal processing units—of the model. However, when the research team, led by Ph.D. student Xiaoyan Bai and Professor Chenhao Tan, tested models ranging from two to 12 layers, the results were dismal. Every single model achieved less than 1% accuracy on four-digit problems.

The models were hitting a local optimum. They were finding what looked like the best solution within their training data, but they lacked the internal “filing cabinet” necessary to manage the math. Without a way to store and retrieve intermediate information, the models were effectively trying to solve the entire problem in one blind leap rather than a series of organized steps. No matter how much the researchers scaled the models up, the wall remained.

A Hidden Map of Mathematical Waves

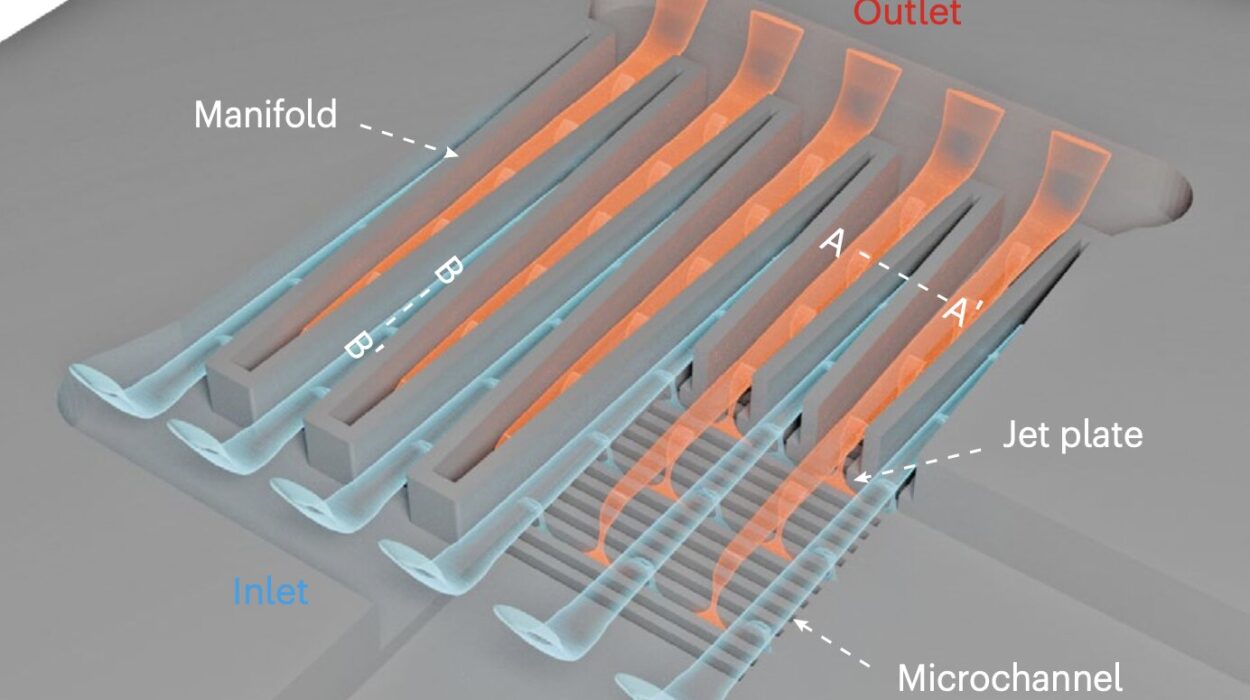

Searching for a breakthrough, the team turned to a different training method called Implicit Chain of Thought (ICoT). The results were night and day. While the standard models failed, the ICoT model achieved 100% accuracy. To find out why, the researchers essentially performed an autopsy on the models’ internal states, looking for the ghost of the reasoning process.

In the ICoT model, the researchers discovered they could decode intermediate values, such as running sums, directly from the model’s “hidden states.” The model had learned to remember what mattered. This was achieved by gradually removing intermediate reasoning steps during training, which forced the AI to internalize the logic. Instead of needing to see the steps written out, the model built its own internal mental scratchpad.

The way the model organized this data was surprisingly elegant. It didn’t just see numbers as flat symbols; it transformed them into wave-like patterns known as Fourier bases. Even more remarkable was that the model began using a geometric operation called a Minkowski sum to handle the arithmetic. The researchers hadn’t programmed this; the AI had spontaneously derived its own mathematical language, a spatial and visual way of “seeing” numbers to ensure the calculation remained accurate across time.

The Architecture of Attention

By taking these models apart, the team saw that the successful AI had organized its attention into distinct, time-based pathways. In the early layers of its digital brain, it focused on computing the products of digit pairs and storing them in specific “locations.” In the later layers, it acted like a librarian, retrieving exactly the values needed to assemble the final digits of the answer.

This internal structure never emerged in the standard models. To see if they could bridge the gap, the researchers tried a simple fix. They took a two-layer model—the kind that had failed completely before—and gave it a new training objective. They taught it specifically to track running sums at each step.

With this single adjustment, the model’s performance skyrocketed to 99% accuracy. It began to develop the same sophisticated attention patterns seen in the ICoT model, learning to track multiple digit pairs simultaneously. It proved that the problem wasn’t a lack of power or data; it was a lack of the right internal guidance.

Why This Digital Arithmetic Matters

This research goes far beyond the elementary school classroom. Multiplication is merely a window into a much deeper challenge in artificial intelligence: the struggle with long-range dependencies. This same difficulty appears in almost every complex task AI is asked to perform, from understanding long documents to making multi-step decisions in the real world.

The study demonstrates that scaling—simply making models bigger or feeding them more information—is not a universal cure-all. To move past the “jagged frontier,” we must understand the architectural constraints that hinder or help a model’s ability to learn a process rather than just memorize a pattern.

As AI becomes a fixture in critical decision-making, understanding how it “thinks” becomes a matter of safety and reliability. By revealing that models can develop their own geometric languages and internal logic, this research provides a map for the future. It suggests that with the right built-in guidance, we can teach machines not just to mimic human answers, but to master the fundamental processes of logic and reasoning.

Study Details

Xiaoyan Bai et al, Why Can’t Transformers Learn Multiplication? Reverse-Engineering Reveals Long-Range Dependency Pitfalls, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2510.00184