In the evolving world of flexible electronics, the dream has always been to mimic the seamless complexity of human skin. Our own skin is a marvel of biological engineering, capable of feeling the stretch of a muscle, the speed of a movement, and the warmth of a touch all at once. For years, scientists trying to replicate this in machines faced a frustrating architectural wall. To build a sensor that could “feel” multiple things, they had to stack layers of different materials like a microscopic club sandwich. One layer would track stretching, another would measure heat, and a third would monitor movement speed. This traditional approach created bulky, complex devices that required messy wiring and external power sources, making them too fragile and cumbersome for real-world use in wearable tech or advanced robotics.

Researchers at the Institute of Metal Research (IMR) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences looked at this complexity and saw a different path. Led by Prof. Tai Kaiping, the team set out to find a way to distill these multiple sensations into a single, elegant layer. They wanted to create a material that didn’t just perform one job, but acted as a multi-talented conductor, translating different physical forces into clear electrical signals simultaneously. The challenge was deep-rooted in physics: usually, the electrical signals generated by heat and those generated by physical pressure move in ways that interfere with each other or require different directions of travel within the material. Breaking this barrier required more than just a new material; it required a total rethink of how microscopic structures are built.

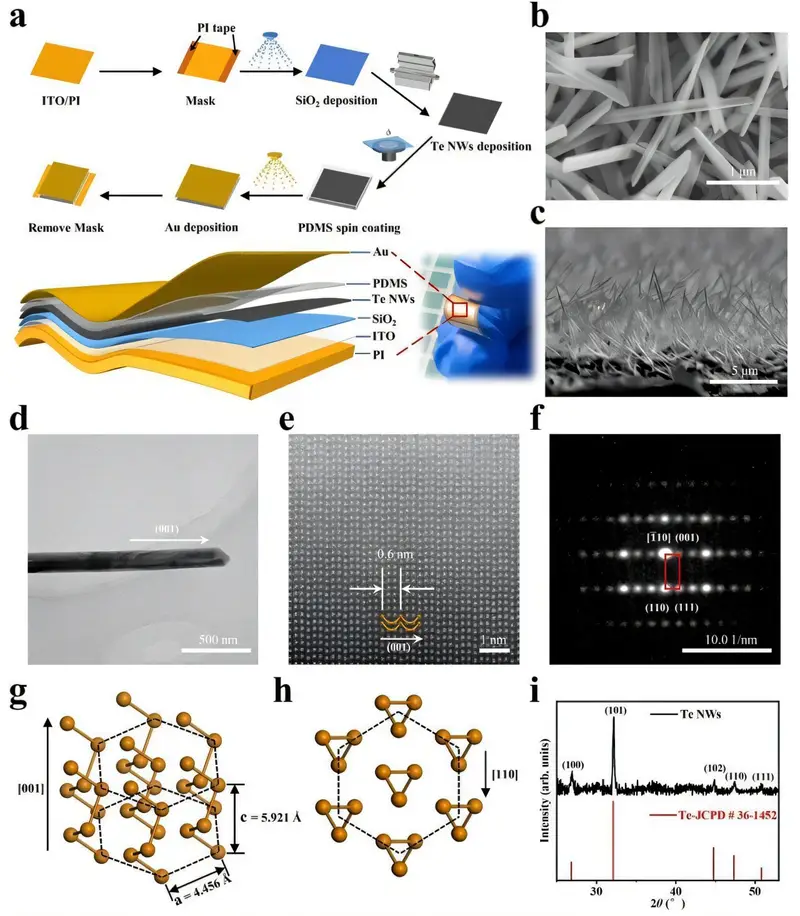

Orchestrating the Nanowire Forest

The breakthrough came in the form of tellurium nanowires (Te-NWs). These tiny, hair-like structures possess unique physical properties, but the researchers realized that simply using them wasn’t enough. They had to engineer the way these wires were positioned. By creating a specially designed network where the wires were tilted at specific angles, they managed to overcome a fundamental limitation of physics. In standard materials, thermoelectric signals (triggered by temperature changes) and piezoelectric signals (triggered by physical strain) often cannot be collected in the same direction. This “traffic jam” of data is why previous sensors needed so many layers.

By tilting the tellurium nanowires, the team created a unique architecture that allowed both signals to be detected and output in the same out-of-plane direction. This was a landmark achievement in material and structural engineering. It meant that for the first time, a single active layer could act as a sophisticated translator for three different types of information. When the sensor is stretched, it registers strain. When that stretch happens quickly or slowly, it captures the strain rate. And even as these physical movements occur, it can still feel the temperature of the environment. All of these inputs are processed through a single channel, eliminating the need for the bulky, multilayered designs that have held the field back for a decade.

The Symphony of Subatomic Forces

To understand why this works, the researchers looked deep into the heart of the atoms themselves. Through first-principles calculations, the study revealed a fascinating dance of subatomic particles. When the tellurium (Te) atoms are subjected to physical force, a charge redistribution occurs. This shift in the internal electrical balance is what generates the piezoelectric effects, effectively turning mechanical pressure into an electrical “voice” that a computer can understand. But the story doesn’t end with pressure alone. The researchers found that external fields, such as thermoelectric potentials created by heat, actually modulate these signals.

This discovery is a masterclass in multi-physics coupling effects. By understanding how heat and movement influence each other at the atomic level, the team was able to calibrate their sensor to reach levels of precision that were previously thought impossible for a single-layer device. The data speaks for itself. The new sensor achieved a strain sensitivity of 0.454 V, a strain rate sensitivity of 0.0154 V·s, and a temperature sensitivity of 225.1 μV·K⁻¹. These numbers don’t just represent incremental progress; they represent a leap forward, surpassing the performance of nearly every previously reported multimodal sensor. By treating the material as a unified system where heat and motion work together rather than competing, the team unlocked a new level of sensing clarity.

Moving Beyond the Static

One of the most significant aspects of this research is the focus on strain rate. In the past, many sensors were good at telling you how much something was stretched, but they struggled to communicate how fast that stretch was happening. In the real world, speed is everything. A robotic hand needs to know not just that it is closing, but how quickly it is snapping shut. A medical monitor needs to distinguish between the slow swell of a breath and the sharp jerk of a sudden movement. The researchers emphasized that this strain rate sensing is vital for dynamic scenarios, where the rate of deformation changes how a material responds to its environment.

By integrating this capability into a single-channel multimodal sensor, the team has simplified the “nervous system” of future electronics. Because the device functions as a nanogenerator, it hints at a future where sensors are more self-sufficient and less dependent on the complex external power supplies that limit current wearable technology. The simplicity of the design—using one active material layer rather than a stack—makes the entire system more reliable and easier to manufacture. It moves us away from the “clunky” era of flexible electronics and toward a future where our devices are as thin, responsive, and intuitive as the skin they are meant to mimic.

Why This Scientific Leap Matters

This research, recently published in Nature Communications, is more than just a victory for laboratory physics; it is a blueprint for the next generation of human-machine interaction. By proving that a single layer of tellurium nanowires can handle the complex tasks of three separate sensors, the researchers have cleared a path for massive advancements in artificial intelligence and biomedical monitoring. In the world of AI, this technology could provide robots with a sense of touch that is far more nuanced and human-like, allowing them to handle delicate objects or navigate unpredictable environments with greater safety.

In the realm of healthcare, the implications are equally profound. Flexible electronics that can simultaneously monitor a patient’s movement, heart rate, and body temperature without requiring a vest full of wires could revolutionize long-term patient care. Because the sensor is thin, flexible, and highly sensitive, it can be integrated into “smart” bandages or wearable patches that provide continuous, high-fidelity data to doctors. Ultimately, this work provides the foundational “new insights” needed to build coupled systems that are smaller, tougher, and smarter, bringing us one step closer to technology that doesn’t just sit on our skin, but understands the world exactly the way our skin does.

Study Details

Hao Zeng et al, Simultaneous strain, strain rate and temperature sensing based on a single active layer of Te nanowires, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65815-8