The question seems almost irresistible in its simplicity. If the universe exists, if it has structure, size, and history, then surely it must have a center. Human intuition, shaped by everyday experience, demands it. Cities have centers, circles have centers, galaxies have centers. Even storms swirl around a central eye. So when we look up at the night sky and imagine the vastness of the cosmos, it feels natural to ask: where is the center of the universe?

For centuries, this question has haunted philosophers, theologians, and scientists alike. It has shaped worldviews, fueled revolutions in thought, and forced humanity to repeatedly confront its own assumptions about place and importance. Yet the answer given by modern physics is not only counterintuitive, but profoundly transformative. The center of the universe is not where most people expect it to be. In fact, according to our best scientific understanding, the universe may not have a center at all.

To understand why this is the case, we must journey through history, cosmology, and the deep structure of space and time itself. Along the way, we will discover that the question of the universe’s center is not merely about location. It is about how reality is shaped, how expansion works, and how human intuition struggles—and sometimes fails—to grasp cosmic truth.

The Ancient Desire for a Cosmic Center

Long before telescopes and equations, the idea of a cosmic center carried deep meaning. In ancient civilizations, the universe was not just a physical structure but a moral and spiritual one. The center often symbolized order, stability, and significance. To be at the center of the universe was to be at the heart of creation.

In many early cosmologies, Earth occupied this privileged position. Ancient Greek thinkers such as Aristotle envisioned a universe composed of concentric spheres, with Earth fixed motionless at the center. The Sun, Moon, planets, and stars revolved around it in perfect circular paths. This geocentric model aligned well with everyday experience: the ground beneath one’s feet felt unmoving, while the heavens appeared to rotate overhead.

This idea was not merely scientific; it was philosophical and cultural. Humanity’s central position in the cosmos reinforced a sense of cosmic importance. The universe, in this view, was structured around human existence. The question of the universe’s center was therefore inseparable from questions of meaning and purpose.

Yet this comforting picture would not survive the rise of modern science.

The First Great Displacement: Earth Leaves the Center

The Copernican Revolution of the sixteenth century marked the first major challenge to the idea of a universal center. Nicolaus Copernicus proposed that Earth is not stationary, but instead orbits the Sun. This heliocentric model simplified the explanation of planetary motion and gradually gained support through the work of Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton.

Although revolutionary, heliocentrism did not entirely erase the concept of a center. It merely shifted it. The Sun replaced Earth as the central anchor of the cosmic system. The universe still seemed structured around a focal point, even if humanity no longer occupied it.

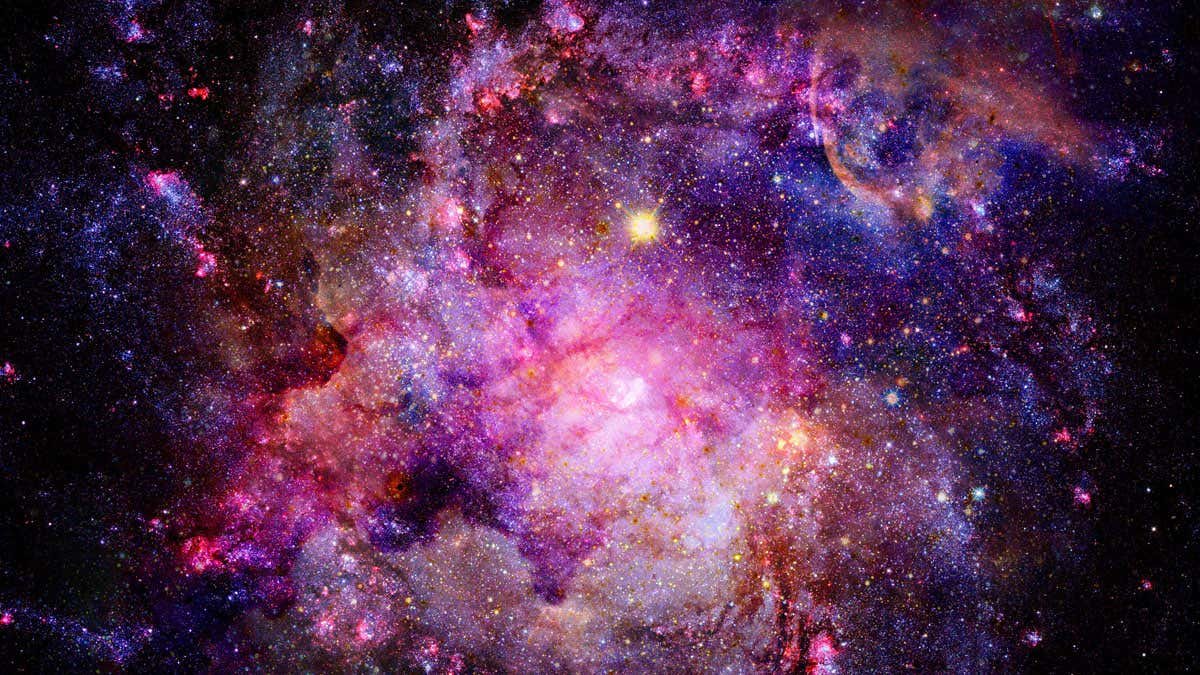

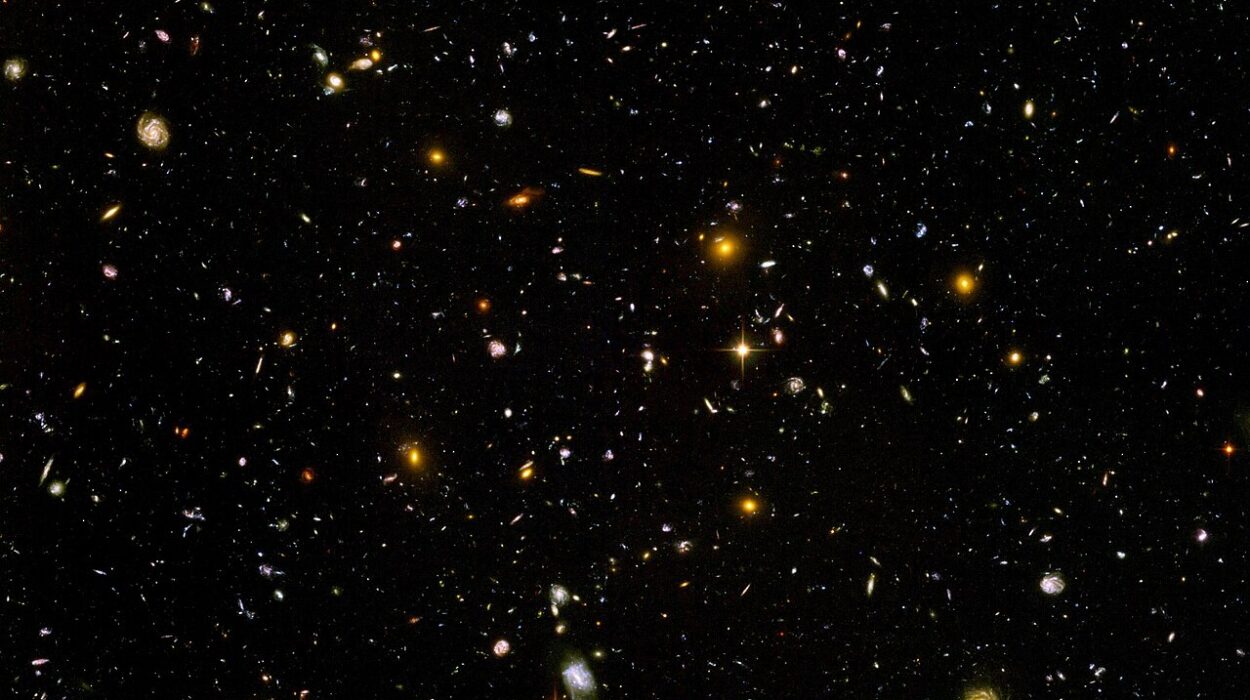

As telescopes improved, astronomers discovered that the Sun itself is just one star among many in the Milky Way galaxy. By the early twentieth century, it became clear that the Milky Way is not the entire universe but one galaxy among billions. The idea of a single, privileged center began to erode further.

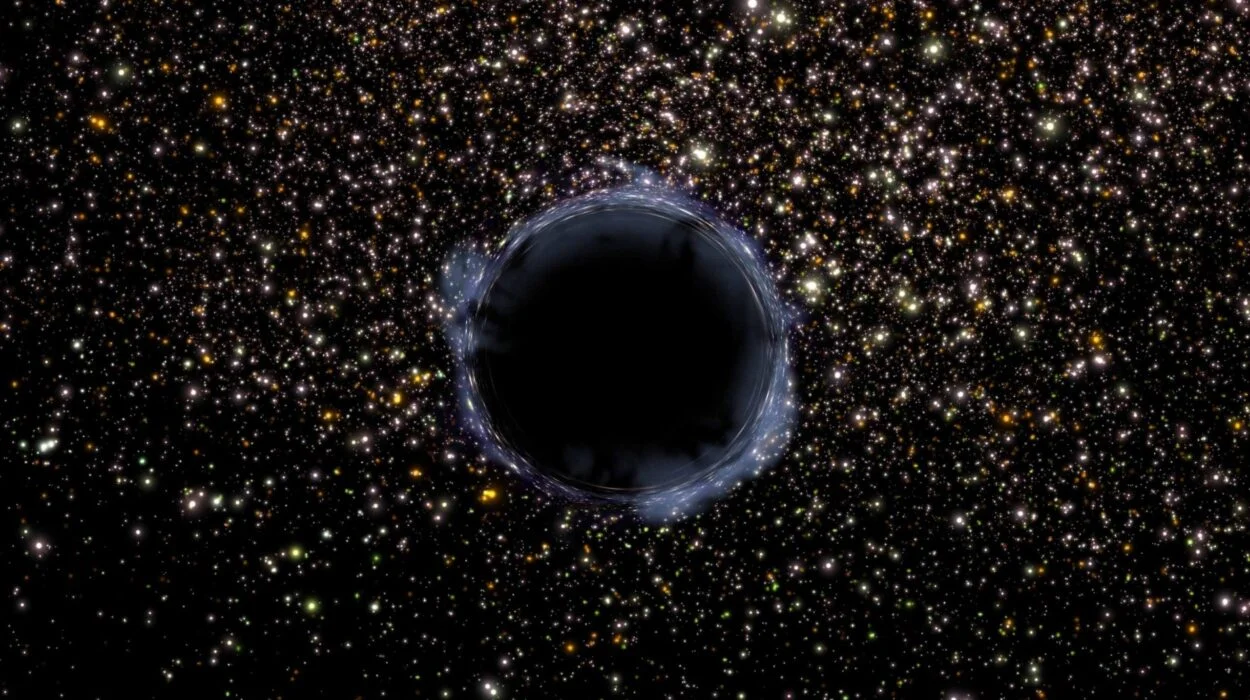

Yet even galaxies have centers. The Milky Way revolves around a dense core containing a supermassive black hole. Could this galactic center be the center of the universe? Or perhaps the center lies somewhere among the largest cosmic structures, where matter seems densest?

Modern cosmology would ultimately deliver an answer far stranger than any of these possibilities.

The Expanding Universe and the Birth of Modern Cosmology

The key to understanding the universe’s center lies in one of the most profound discoveries of twentieth-century science: the expansion of the universe. In the 1920s, astronomer Edwin Hubble observed that distant galaxies are moving away from us, with their light stretched to longer, redder wavelengths. This phenomenon, known as redshift, revealed that space itself is expanding.

The crucial insight was not merely that galaxies are moving through space, but that the fabric of space itself is stretching. The farther away a galaxy is, the faster it appears to recede. This pattern is consistent in all directions, suggesting that expansion is uniform.

At first glance, this seems to imply a center. After all, if everything is moving away, shouldn’t there be a point from which everything is fleeing? This intuition, however, turns out to be misleading.

To understand why, we must rethink what we mean by expansion and distance on cosmic scales.

The Big Bang and the Illusion of a Central Point

The discovery of cosmic expansion led naturally to the idea of the Big Bang: the universe began in a hot, dense state and has been expanding ever since. Popular imagination often depicts the Big Bang as an explosion occurring at a specific point in space, with matter flying outward into emptiness. If this were true, that point would indeed be the center of the universe.

But this picture is fundamentally incorrect.

The Big Bang was not an explosion in space; it was an expansion of space itself. All regions of the universe were once compressed together, not gathered at a single location within a larger preexisting space. Space itself came into being with the Big Bang, and it expanded everywhere at once.

This distinction is crucial. If space itself is expanding uniformly, then every location can legitimately be described as the center from its own perspective. Observers in distant galaxies would see the same pattern of expansion that we see, with other galaxies receding from them in all directions.

There is no privileged point from which expansion began. The universe did not expand from a center into surrounding emptiness. It expanded internally, like the surface of an inflating balloon, where every point moves away from every other point.

The Balloon Analogy and Its Limits

One of the most effective ways to visualize cosmic expansion is the balloon analogy. Imagine dots drawn on the surface of a balloon. As the balloon inflates, the dots move farther apart. No dot is the center of the expansion on the surface itself. The expansion occurs everywhere on the surface simultaneously.

From the perspective of any single dot, all other dots appear to be moving away. Yet there is no special dot that occupies a central position on the surface. The center of the balloon exists only in a higher-dimensional space, not within the surface itself.

Our universe behaves in a similar way, though with important differences. We are not living on a two-dimensional surface but in a three-dimensional space. The expansion of the universe does not require an external center or higher-dimensional reference point. It is a property of spacetime itself, as described by Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

The balloon analogy helps illustrate why asking for a center within the universe may be a flawed question. It assumes a structure that may not exist.

General Relativity and the Nature of Spacetime

Einstein’s general theory of relativity provides the mathematical framework that underpins modern cosmology. According to this theory, space and time are not passive backgrounds but dynamic entities influenced by matter and energy. The geometry of spacetime determines how objects move, and the distribution of matter determines how spacetime curves.

In cosmological models derived from general relativity, the universe is described as homogeneous and isotropic on large scales. Homogeneity means that the universe is roughly the same everywhere; isotropy means it looks the same in all directions. These assumptions are strongly supported by observations, including measurements of the cosmic microwave background radiation.

A universe that is homogeneous and isotropic cannot have a unique center within itself. Any point can be considered equivalent to any other. The laws of physics operate the same way everywhere, and no location enjoys a privileged status.

In this framework, the concept of a center becomes unnecessary and even meaningless. The universe is not organized around a focal point but is structured according to universal laws that apply uniformly throughout space.

The Observable Universe and a Misleading Center

There is, however, a sense in which each observer appears to occupy a central position. When astronomers speak of the observable universe, they refer to the region of the cosmos from which light has had time to reach us since the Big Bang. This region has a finite size, determined by the age of the universe and the speed of light.

From our perspective, we are at the center of this observable universe. In every direction, we see galaxies receding, and beyond a certain distance, the universe becomes opaque, marked by the cosmic microwave background.

But this center is not a physical feature of the universe itself. It is an observational artifact. Any observer, anywhere in the universe, would find themselves at the center of their own observable universe. This does not confer special status; it reflects the limits imposed by time and the finite speed of light.

Confusing the center of the observable universe with the center of the universe as a whole is a common but significant mistake.

Does the Universe Have an Edge?

The question of a center is often tied to the question of an edge. If the universe has a center, perhaps it also has boundaries. Yet modern cosmology suggests that the universe may be finite without having an edge, or infinite without having a center.

In certain models, space is curved in such a way that traveling far enough in one direction could, in principle, bring you back to your starting point, much like circumnavigating the surface of a sphere. Such a universe would be finite in volume but unbounded. There would be no edge to fall off, and no central point within the space itself.

Alternatively, the universe may be infinite, extending endlessly in all directions. In this case, the idea of a center becomes even more problematic. An infinite, homogeneous space has no distinguished point that can serve as a center.

Current observations cannot definitively determine the global shape and extent of the universe. What they do strongly indicate is that, whatever the universe’s ultimate structure, it does not include a central point in the way human intuition expects.

The Emotional Challenge of a Centerless Universe

The idea that the universe has no center can be unsettling. For much of human history, cosmological models reinforced a sense of belonging and significance. To remove the center is to remove a comforting anchor.

Yet this realization can also be liberating. A universe without a center is not a universe that excludes us. Rather, it is one that includes us fully, without hierarchy. Every location is as fundamental as every other. The laws of physics do not privilege one region over another.

In this sense, the absence of a center affirms a deep principle of modern science: the universality of natural law. The same physical rules that govern distant galaxies govern the atoms in our bodies. We are not spectators watching a cosmic drama from the sidelines; we are participants within the same unfolding structure.

Common Misconceptions About the Universe’s Center

Despite the clarity of modern cosmology, misconceptions persist. Some imagine the Big Bang as a point in space that can be located if only we look far enough. Others confuse the center of the Milky Way or the densest region of matter with a universal center.

These ideas often arise from applying everyday spatial intuition to a domain where it no longer applies. On Earth, expansion and motion typically occur within a fixed background. In the universe, the background itself evolves.

Physics teaches that intuition, while valuable, must be tested and refined. The history of cosmology is a record of humanity learning to let go of assumptions that feel obvious but prove false under careful scrutiny.

The Center as a Question of Perspective

Perhaps the most surprising answer to the question of the universe’s center is this: from a certain perspective, you are at the center. Not because your location is special, but because the laws of physics ensure that every observer experiences the universe as expanding away from them.

This perspective does not restore human centrality in a traditional sense. Instead, it reflects a profound symmetry built into the cosmos. The universe does not revolve around us, but neither does it exclude us. It allows every observer to legitimately describe themselves as central, without contradiction.

This insight captures something deeply philosophical about modern physics. Reality is not organized around absolute reference points. Meaning emerges from relationships, from how things interact and are observed.

Why the Question Still Matters

If the universe has no center, why does the question continue to fascinate? Because it touches on more than geometry. It touches on identity, significance, and the limits of human understanding.

Asking where the center of the universe is forces us to confront the difference between how the universe feels and how it actually works. It reminds us that science often advances by challenging deeply held intuitions. It also highlights the power of abstract reasoning and mathematical models to reveal truths inaccessible to direct experience.

In grappling with this question, we participate in a tradition that stretches back to the earliest thinkers who looked at the sky and wondered what it all meant.

The Surprising Truth

So where is the center of the universe? According to modern physics, it is nowhere—and everywhere. The universe does not have a central point embedded within space. It expands uniformly, governed by laws that apply equally across all regions.

This answer may surprise, even disappoint, those who expect a more concrete location. But it reveals something far more profound. The universe is not built around a single point of importance. It is a vast, dynamic whole in which every place is woven into the same cosmic fabric.

In accepting a centerless universe, we gain not a loss of meaning, but a deeper understanding of our place in reality. We are not standing at the center of all things, yet we are inseparably part of the universe’s structure and history. The same expansion that carries distant galaxies away also carries us forward through time.

The universe has no center, but it has coherence, beauty, and laws that can be known. And in seeking to understand those laws, humanity finds a different kind of centrality—not of position, but of participation in the ongoing story of the cosmos.